Are YOU Being Honest? The Truth Hurts

Podcast by The Mindful Minute with Autumn and Rachel

Hidden Motive in Everyday Life

Are YOU Being Honest? The Truth Hurts

Part 1

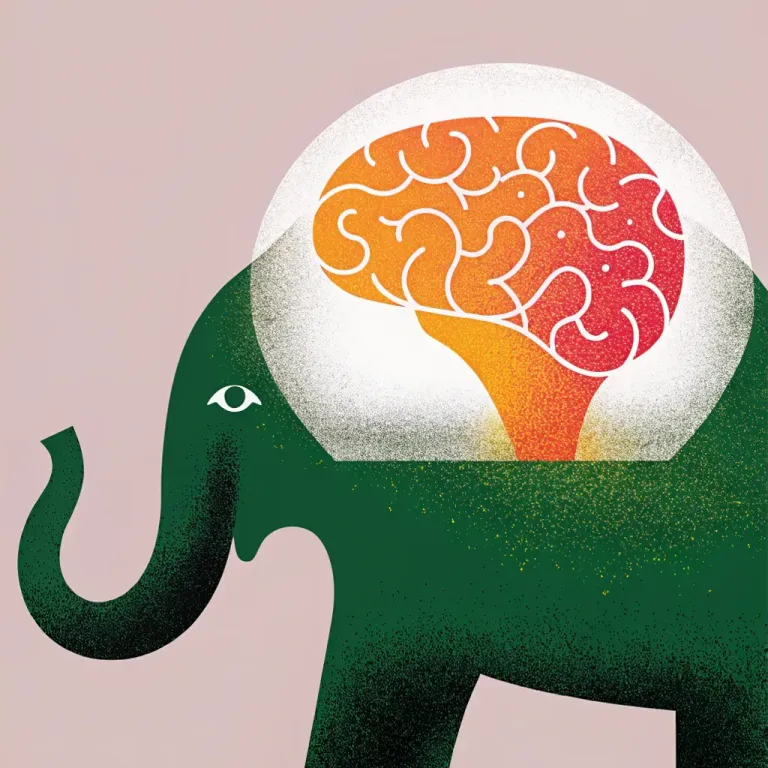

Autumn: Hey everyone, welcome back! Today we're jumping into a topic that's both super interesting and, well, a little unsettling: the hidden motives behind our actions. Have you ever stopped to wonder why you do certain things? I mean, we like to think it's all about being a good person, right? But is that really the whole story? Rachel: Sneaky motives, huh? Like, you see someone making a big show of donating to some charity, and suddenly their name's all over the event. You gotta wonder, is that about helping the cause or, you know, boosting their own image? Autumn: Exactly! That's the whole idea we're exploring today. It all comes from this book called The Elephant in the Brain: Hidden Motives in Everyday Life by Kevin Simler and Robin Hanson. It basically argues that a lot of our decisions are driven by motives we don't even admit to ourselves. Rachel: Right, so even those actions that seem super selfless or logical might have a secret agenda, like self-interest or showing off. Whether that's going to the doctor, donating, or even getting an education, there's usually an "elephant in the room"—the real reason we're doing it. Autumn: So, we’re going to break this down into three parts today. First, we'll look at why we might act out of self-interest, even when we think we're being all altruistic. Are we really helping others, or are we just trying to look like heroes? Rachel: Then, we'll dig a little deeper and check out the evolutionary roots of these hidden motives. Big spoiler: it probably comes down to survival and snagging resources, maybe even tricking ourselves to get ahead. Autumn: And finally, we’ll see how these hidden motives pop up in the big systems around us—like medicine, school, religion, and even politics. Turns out, these aren't always as virtuous as we think they are. Rachel: Virtuous? Autumn, more like intricate games where everyone's trying to one-up each other . I'm always curious to see how deep this rabbit hole goes. Autumn: And that's why this is so important! By facing these “elephants” head-on, we can maybe understand ourselves and society a little bit better. So, let's dive in, shall we?

Hidden Motives in Human Behavior

Part 2

Autumn: Okay, let’s dive into hidden motives. The core idea is, while we love to think we're all about altruism and pure logic, a lot of what we do is driven by self-interest and social signaling. Basically, there’s this underlying 'why' behind our actions that often stays hidden, even from ourselves. Rachel: So, the book isn't saying we're all mustache-twirling villains plotting for personal gain, right? It's more nuanced than that. Autumn: Exactly! Hidden motives aren’t necessarily malicious. They're more like evolutionary tools that help us navigate social situations. When we seem altruistic, there’s often an underlying driver—like gaining social status, showing we’re trustworthy, or strengthening relationships. What’s really interesting is this concept of self-deception. We convince ourselves we're acting with pure intentions, which, in turn, makes us better at convincing others. It’s like an evolutionary superpower for social survival. Rachel: Ah, the old "lie to yourself to lie better to others" trick. Clever! Autumn, give me a clear example. How does this self-deception thing actually play out in real life? Autumn: Sure. Imagine a manager who's always pushing "teamwork" and "collaboration." On the surface, it looks like they're building unity for the good of the group. Noble, right? But, if we look through the lens of hidden motives, their behavior might also be about gaining loyalty, keeping their authority intact, or even taking credit for the team's successes. Rachel: So, instead of being a harmony cheerleader, they might just be protecting their position or racking up achievements. And they might not even realize they're doing it? Autumn: Exactly! That’s the beauty—and the danger—of self-deception. It's not just hiding ulterior motives from others, but also from ourselves. By really believing in their altruism, they sell it more convincingly. It’s like a double-layered performance, and everyone’s buying a ticket. Rachel: So, in this case, altruism is just branding, like a company slapping "eco-friendly" on a package while still creating tons of waste. Except, here, it's happening internally. Fascinating... and a little unsettling. Autumn: It can definitely make you rethink your own actions. And this leads us to one of the most relatable examples of hidden motives: charitable giving. We usually associate it with pure altruism, but when you dig deeper, it reveals a lot about our habits related to social signaling. Rachel: Ah, charity—the ultimate playground for hidden motives. I bet you’re going to tell me those huge checks at fancy galas aren't purely about saving the whales. Autumn: Well, in many cases, no. Studies show people tend to give more when their donations are visible. Like, at public fundraising events where contributions are tracked or announced, donations skyrocket. But, when it comes to anonymous giving, the same people might donate significantly less. Rachel: Right, because when donations are public, you're not just feeding hungry children or saving rainforests. You’re feeding your ego and saving your reputation, too. Makes sense. Someone’s applause can be as valuable as the cause itself. Autumn: That's a great point, and it's grounded in signaling theory. Public donations signal things like generosity, wealth, and a sense of moral integrity. And let’s not forget the emotional reward. People also give because it makes them feel good, reinforcing their self-image as a compassionate person. Rachel: Let me guess—there's also a hierarchy here. People probably favor donations that get them the most recognition or emotional satisfaction. Like, why fund a clean water pipeline for some faraway village when you can fund the shiny new library in your own neighborhood… and get your name on a plaque? Autumn: Spot on! We see that time and again. Local or visible causes that offer tangible results tend to get more attention than global, systemic issues that lack immediate recognition. It’s a great example of how proximity and acknowledgment drive behavior, even when the stated intention is altruism. Rachel: So really, it's not just about helping, it's about being seen helping. Kind of like when people upload their act of kindness to social media with a #blessed hashtag. I’m sure the gesture is genuine but... maybe also a little performative? Autumn: Exactly! And social media has amplified this, giving us all a stage where acts of kindness can be broadcast to thousands. But, it doesn’t mean there’s no real intent. These hidden motives are a mix of wanting to help and wanting to be acknowledged. Rachel: Alright, so we’ve established that most of us are walking, talking PR campaigns, constantly spinning narratives about how great we are. But what happens when there’s a clear gap between what people say they value—like helping others—and what they actually do? Autumn: That's another fascinating aspect: the gap between intent and action. Take philanthropy. Many people say they care deeply about global issues like poverty or education in faraway places. But if they have to choose between funding those causes or getting a new phone, most people would choose the phone. Rachel: Right, because the new phone is tangible. They can hold it, enjoy it, and, let's be honest, show it off. Sending aid to another country? Less so. There’s no immediate benefit, no applause, and sometimes, no real sense that they’ve made a difference. Autumn: Exactly. People lean toward things that feel impactful “and” visible. Global causes often offer neither. Meanwhile, local and emotionally compelling projects, like supporting a nearby shelter, give donors both recognition and a concrete result they can see and value. Rachel: Meaning our charitable actions are fundamentally shaped by what we get out of them. Whether it’s social status, emotional satisfaction, or moral credit, there’s almost always something in it for us. Autumn: And understanding these dynamics starts with awareness—pausing to ask ourselves why we're making certain choices. Take that moment to ask: Is my motive really about the cause, or am I seeking recognition? That kind of reflection can really improve more authentic behaviors. Rachel: And by “authentic,” you mean stripping away the invisible PR campaign we’re constantly running. Seems tough, especially when these hidden motives are so deeply ingrained in who we are. Autumn: True, but it’s not about eliminating hidden motives altogether. It’s about recognizing and balancing them—acting in ways that align with our conscious values while understanding the subtle forces at play.

Evolutionary and Social Frameworks

Part 3

Autumn: So, understanding these hidden motives? It really comes down to the evolutionary and social factors that support them. This next part, it builds on what we've already discussed, looking at how evolutionary psychology and social norms play into this idea of hidden motives. By understanding the science behind it, we can see why behaviors that seem really generous or helpful often have pretty deep evolutionary roots. Rachel: Okay, so we're shifting from "here's why you're not as selfless as you think" to "here's why you evolved to be sneaky like that." Makes sense. So, where do you want to start with these frameworks? Autumn: Let's start with an example from the animal kingdom that relates directly to us: social grooming among primates. On the surface, it looks simple, right? One chimp grooming another to keep them clean. But research shows there's a lot more strategy involved than just hygiene. Rachel: Strategic, huh? Are these chimps, like, plotting something in their little furry minds? Autumn: Kind of! Grooming builds alliances, shows loyalty, and sort of maintains the social order within the group. For example, a lower-ranking chimp would groom a higher-ranking one to gain favor, maybe get some protection. It's like forming alliances at work – you befriend the boss so you're in a good position when it's time for raises or promotions. Rachel: Right, I see where you're going with this. And the stronger those bonds, the more likely you are to benefit during conflicts or disputes within the group. So grooming is basically their networking? Meaning LinkedIn isn't as modern as we think it is. Autumn: Exactly! And animals spend a lot of time on this stuff. Gelada baboons, for instance, spend up to 17% of their day grooming! Which shows how crucial it is for maintaining social harmony. It's not that different from humans who take colleagues out for coffee or send holiday gifts to clients. What looks generous or thoughtful often has a purpose – strengthening ties within a hierarchy. Rachel: So while it looks like they're just scratching itches, they're actually cutting backroom deals to secure resources or allies. Clever. It's amazing how this translates to humans. Like, politeness, compliments, small favors... they aren't just "nice." They're actually tools, right? Autumn: Precisely. These gestures, whether it's complimenting a coworker on their presentation or buying a gift for a friend, they often serve multiple purposes. Yes, they're kind, but they also signal that you're reliable, trustworthy, and cooperative. These are traits that improve your social standing. Rachel: And the more visible these acts are, the better they work, right? Isn't that where we see overlaps with competitive altruism? You mentioned the Arabian babbler earlier, those little desert birds competing to be the most helpful. Let's dive into that. Autumn: Yeah, the Arabian babblers are a great example of what's called "competitive altruism." These birds perform altruistic acts – sharing food, standing guard to warn of predators. Seems noble at first, but it's actually a competition. The more noticeable and risky the act, the higher their status, which gives them better access to mates and resources. Rachel: So it's less "selfless hero" and more “a job interview under the scorching sun.” They're auditioning for recognition. If I remember correctly, aren't they allegedly jockeying to one-up each other in those generous acts? Autumn: Exactly! If one bird offers food, another might swoop in to offer it instead, essentially out-gifting the first bird. It's similar to humans competing to sponsor the biggest scholarship fund or make the most impressive donation to a charity. Rachel: Or when two people fight over the bill at dinner, each trying to look like the most generous person at the table. It seems selfless, but it's also kind of a power play. Autumn: Exactly. And the idea of competitive altruism carries over into human behavior, where visibility is key. Publicly generous acts, like volunteering in leadership roles or hosting charity events, often elevate someone's social status. In competitive environments, signaling altruism becomes an advantage, just like it does for the babblers. Rachel: So, let me ask you this: why do humans—and these birds, for that matter—go out of their way to hide that it's a competition? Why not just own it? Autumn: That ties into our evolutionary need to cooperate. If your motives are too obvious, you could appear opportunistic, and that undermines the social structure. Self-deception plays a big role here. By truly believing we're acting altruistically, we become more convincing to others. It masks our hidden agendas long enough to maintain trust. Rachel: So, to stay at the top of the social heap, you need two skills: compete visibly for status and simultaneously convince everyone—including yourself—that you're not competing at all. That's Olympic-level social strategy. Autumn: Basically, yeah! And humans are masters of it. Think about how things work at your workplace. A team member might volunteer to lead a project. Seems great, like they are stepping up for the team! But in the background, that role can signal ambition or position them for career advancement. Rachel: It's ingenious and diabolical all at once. And it explains why we often hide our competitive instincts. If someone seems too ambitious, it can make them vulnerable to pushback, even sabotage. By concealing their motives, they sidestep those risks. Autumn: It's all about navigating social dynamics, which brings us to "honest signals." That's a concept the book uses to describe behaviors that genuinely reflect someone's value or commitment. Rachel: Honest signals, huh? Sounds like an antidote to all this clever deception. What makes a signal "honest?" Autumn: Honest signals are costly behaviors – actions that require real effort, risk, or sacrifice, making them difficult to fake. The Arabian babblers standing guard while risking their lives? That's an honest signal of commitment to the group. Or humans donating anonymously or mentoring others without seeking recognition. Rachel: So, I take it that honest signals can’t simply be risky. There should be long-term benefits to them as well, right? Because altruism without the potential for some return isn't really a sustainable evolutionary strategy. Autumn: Totally, patterns of behavior that yield indirect but lasting advantages—like a better reputation or more durable alliances—tend to be deeply rooted in self-interest disguised as altruism. Spotting these patterns helps us understand the full mix of human motives. Rachel: So what's the ultimate takeaway here? Behind every act of kindness or cooperation, there's almost always a strategic angle? Autumn: Not every act, but a lot of them. The evolutionary and social frameworks in this book show that even our best intentions can have self-serving aspects. It's not necessarily cynical – it's a function of survival and social cohesion. Recognizing this can help us understand our own motives and those of others around us. That can help us all engage more consciously in our interactions.

Implications for Modern Institutions

Part 4

Autumn: So, with that foundation, we can really dig into how these hidden motives show up in our institutions and daily lives. You know, education, healthcare, even religion – these systems aren't immune. In fact, they're often shaped by these underlying dynamics. That's why we're looking at how these hidden motives drive the way these institutions work and how they influence our behavior, both individually and collectively. Rachel: Exactly, Autumn. This is where we take all the concepts we've been discussing—hidden motives, self-deception, social signaling—and see how they play out in the real world. We're not just talking about personal quirks anymore. These subconscious motivations actually mold entire systems, and, as we'll see, often lead them to drift pretty far from their original, stated goals. Autumn: Right. Let's start with education, something most of our listeners, and, honestly, all of us, can relate to. The book challenges the common belief that education is mainly about learning—you know, gaining knowledge and skills for future careers. Instead, the authors argue that education often functions as a signaling mechanism. Rachel: Signaling, huh? So, it's less about what you actually learn and more about proving that you're disciplined, reliable, or, uh, just capable of sitting through a three-hour lecture without passing out? Autumn: Pretty much, yeah. The economist Michael Spence's "signaling theory" is key here. He argued that educational achievements signal certain personal traits that employers value—like perseverance, intelligence, and conformity—even more than the practical knowledge you've gained. Rachel: Okay, let's get concrete here. What's the evidence? Why should we believe that education isn't really what it claims to be? Autumn: The "sheepskin effect." That's one of the most compelling arguments for signaling over pure learning. The idea is that simply getting a diploma or degree—the "sheepskin"—leads to a big jump in earnings, far more than what each individual year of schooling contributes. Rachel: You're saying just having that piece of paper is more valuable than, say, retaining Newton's Laws? That explains why so many job listings say "degree required," even for jobs that seem, well, pretty far removed from academia. Autumn: Exactly. Studies show that college grads earn significantly more than those who attended college but didn't finish their degree, even if they completed most of the coursework. Employers aren't just valuing the knowledge gained. They're valuing what the degree signals: that you can navigate a structure, meet deadlines, and persevere. Rachel: That's kind of crazy. It's like saying, "We don't care what you learned. Just prove you can jump through hoops." But, I guess it makes sense. Employers don't have the time to evaluate every applicant's actual skills, so they outsource that vetting process to schools. Autumn: Precisely. And that's where the hidden motives come in. On the surface, students pursue education to gain knowledge and prepare for their careers. But when you dig deeper, many are really there to collect that credential—what the book calls a "fitness display." You see this in behaviors like choosing easier classes or celebrating when a lecture gets canceled. The goal becomes the degree, not the learning itself. Rachel: Okay, Autumn, hold on. Does this mean education is just a performance? What about people who truly value intellectual growth for its own sake? Are they the exception? Autumn: Well, of course there's people who genuinely pursue education for the joy of learning. But the scale of the "sheepskin effect" shows that, for the majority, signaling plays a big role, even if they don't realize it. It's not about dismissing education altogether, it's about recognizing that the system often prioritizes credentials over substance. Rachel: And that has consequences, right? If everyone's focused on the degree, then the education system shifts to accommodate that. You end up with a system that rewards superficial participation, like showing up to class but not engaging, or memorizing for tests without really understanding the material. Autumn: Exactly. And this has implications for society. If education is mainly about signaling, then its role isn't just about teaching skills, you know? It's about sorting people into social and economic hierarchies. But that's not how we talk about it. We still focus on learning and growth, even when the data tells a different story. Rachel: So we keep investing in an education system designed to “teach,” when a lot of that investment is really about making résumés look good and proving that you're employable. Autumn: And that's the kind of awareness the book encourages. Once you recognize these hidden motives, you can engage with education more critically—thinking about what's truly valuable, both for you and for society. Rachel: That's a great segue to healthcare, where another hidden motive plays a big role: conspicuous caring. Now, this one feels particularly relevant these days, especially with healthcare costs constantly on the rise. Autumn: Absolutely. Healthcare, as we believe, is all about improving health outcomes. But, as the book points out with the "conspicuous caring hypothesis," healthcare consumption often serves a deeper, social signaling function. Rachel: Healthcare as signaling? Alright, walk us through this. Why aren't we just focused on better health, plain and simple? Autumn: Well, the RAND Health Insurance Experiment is a classic study that sheds some light on this. From 1974 to 1982, researchers randomly assigned people different levels of health insurance coverage. Those with full coverage used a lot more medical care—routine checkups, minor treatments—than those with limited coverage. But, when they looked at health outcomes, there wasn't a significant improvement in key metrics. Rachel: Wait, so more checkups, more tests, more treatments—and none of it led to better health? It's like buying an expensive gym membership and never going. Autumn: Exactly. The findings suggest that a lot of that extra care wasn't really tied to health benefits. Instead, it acted as a signal that people cared about their health. Rachel: And let me guess, the more visible or expensive the care—think second opinions from fancy specialists, all the latest diagnostic tests—the more it reinforces that signal. Autumn: Right on. It's like luxury goods. Seeking out high-profile medical care is a public display of concern, showing yourself and others, “I'm committed to well-being, and I have the resources to prove it." Rachel: That's... a little disturbing. I mean, healthcare is supposed to be about saving lives and addressing real needs. But if all this conspicuous caring is eating up resources, doesn't that mean less for those who really need medical treatment? Autumn: That's one of the concerns the book raises. When medical consumption is driven by signaling, it can skew healthcare priorities on a systemic level—putting money and attention toward areas that boost signaling rather than addressing critical health disparities. Rachel: So, you're saying the lines between what we need and what we want get blurred. It reminds me of how extravagance competes with essentials in other industries. Autumn: Exactly. That's why it's so important to recognize these motives—not to judge people, but to think critically about where resources are going and why. It starts a conversation about whether we need to rethink the incentives in healthcare. Rachel: And, just like education, there's a huge gap between the stated goals—health improvement—and what's actually happening. If we can't even be honest about the motives behind these essential institutions, how can we ever expect to reform them for real? Autumn: That's the challenge. But maybe, by identifying the elephant in the room—these hidden social drivers—we can start aligning these systems with their intended purposes.

Conclusion

Part 5

Autumn: So, to wrap things up, today we dove headfirst into the somewhat unsettling world of hidden motives. We explored how much of our behavior—whether it’s in charity work, education, or even healthcare—is actually influenced by self-interest and, you know, social signaling. At its core, “The Elephant in the Brain” asks us to look beyond what we see on the surface and really question what's driving us. Rachel: Right, and we saw that these motives aren't just random little quirks, are they? They’re deeply rooted in our evolutionary past, shaping pretty much everything, from the way baboons groom each other to, well, how extravagantly generous humans can be. And it doesn't stop with individuals, either. These hidden motives kind of ripple outwards, shaping our biggest institutions—like schools and hospitals—and sometimes, you know, veering them way off course from what they say they're supposed to be doing. Autumn: Exactly! But as unsettling as it might be to face all this, there's also a real opportunity here in understanding it. Self-awareness empowers us. It enables us to make more intentional choices and to really critically evaluate the systems we're all interacting with. Rachel: Okay, so here's a thought to leave everyone with: If so many of our decisions are shaped by these unseen motivations, what would happen if we actually tried to bring them into the light? What might change in the way we live, or, you know, the way we give, or even how we structure our entire society? Autumn: It's definitely something to think about. And by looking a little deeper, maybe, just maybe, we can bridge that gap between what we “say” we value and what we actually “do”. Creating systems and actions that truly align with the principles we intend. Rachel: And in the process, maybe we can learn to recognize, if not completely tame, a few of those elephants along the way.