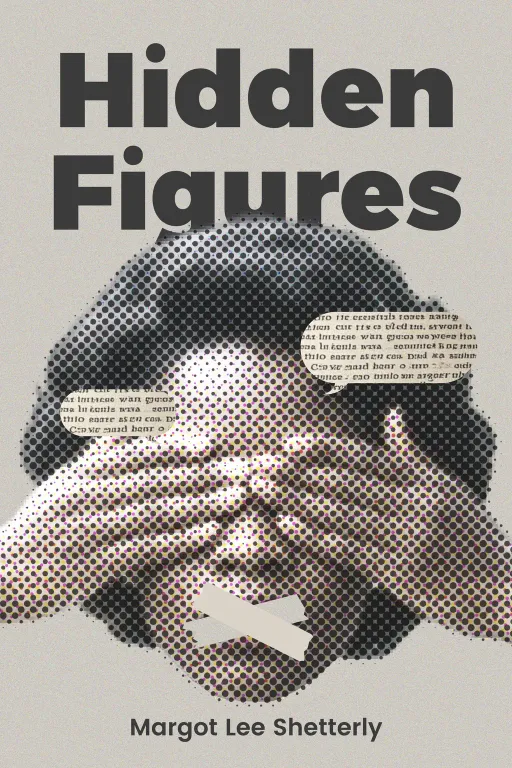

Hidden Figures

10 minThe American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race

Introduction

Narrator: Imagine the scene: February 1962. Astronaut John Glenn is strapped into the Friendship 7 capsule, poised to become the first American to orbit the Earth. The nation holds its breath. But before he gives the final "go," Glenn has one last condition. A new, room-sized IBM electronic computer has plotted his trajectory, a complex web of calculations to guide him through space and bring him home safely. Glenn, a pilot who trusts his gut and his instruments, is wary of the new machine. "Get the girl to check the numbers," he says. "If she says they're good, then I'm ready to go."

That "girl" was Katherine Johnson, a Black mathematician working in a segregated unit at NASA. Her mind was the final, trusted firewall between a national hero and the vast emptiness of space. The story of how she, and dozens of women like her, came to be at the heart of the space race is the subject of Margot Lee Shetterly’s groundbreaking book, Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race. It reveals a history that wasn't just overlooked, but actively erased, and rewrites the narrative of one of America's greatest achievements.

A Door Opens: The Unlikely Alliance of War and Opportunity

Key Insight 1

Narrator: The story of the "hidden figures" begins not with the glamour of the space race, but in the crucible of World War II. By 1943, America was a nation at war, and victory, it was believed, would be won "through airpower." At the Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory in Virginia, the predecessor to NASA, the demand for aeronautical innovation was insatiable. The facility was running three shifts a day, six days a week, and it was desperately short on talent. Personnel officer Melvin Butler sent an urgent telegram to the civil service requesting hundreds of new employees, from physicists to typists. The most critical shortage was in "computers"—not machines, but people, almost exclusively women, who performed the complex calculations that translated raw wind tunnel data into aerodynamic improvements.

This labor crisis created an unprecedented opportunity. But the door for African American women was pried open by a force far from the war front. A. Philip Randolph, a powerful Black labor leader, threatened a massive march on Washington to protest the rampant discrimination in the booming defense industry. To avert a political crisis, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, banning racial discrimination in defense hiring. Nearly two years later, applications from qualified Black female mathematicians began to arrive at Langley. For women like Dorothy Vaughan, a talented math teacher earning just $850 a year in segregated Farmville, Virginia, the offer of a $2,000 annual salary as a mathematician was life-changing. It was a door opened by the dual pressures of global conflict and a determined fight for civil rights at home.

The Double V: Fighting for Victory Abroad and Dignity at Home

Key Insight 2

Narrator: Arriving at Langley did not mean leaving segregation behind. The world these women entered was defined by a concept championed in the Black press: the "Double V," a call for a double victory over fascism abroad and racism at home. This duality was a daily reality. The Hampton Roads area was a chaotic boomtown, but Jim Crow laws governed every aspect of life. Black workers had to ride in the back of overcrowded city buses, often suffering humiliation from drivers.

This segregation was formalized inside Langley itself. Dorothy Vaughan and the other Black mathematicians were assigned to a segregated unit called the West Area Computing section, located in a remote warehouse building. The most galling symbol of their second-class status was a simple, hand-lettered sign in the cafeteria that read "COLORED COMPUTERS." It designated a separate table for them, a constant, demeaning reminder of the color line. But this is where the quiet, personal fight for the Double V took place. A West Computer named Miriam Mann, a small but determined woman, began a campaign of civil disobedience. Every day she would walk into the cafeteria, remove the sign, and slip it into her purse. The next day, the sign would reappear. And the next day, Miriam would remove it again. This silent battle of wills continued until, one day, the sign was gone for good. It was a small victory, but it was a victory nonetheless, won not with protest signs, but with the persistent, dignified refusal to accept indignity.

Forging the Path: From Human Computers to Engineers and Leaders

Key Insight 3

Narrator: The women of West Computing were not content to simply perform calculations; they were determined to advance. Their journeys show the different, difficult paths they had to forge. Dorothy Vaughan quickly distinguished herself not just for her mathematical skill, but for her leadership. She became a fierce advocate for all the women in her unit, both Black and white. In 1949, after her white supervisor suffered a tragic mental breakdown, management was faced with a choice. They named Dorothy the acting head of West Computing, and two years later, made it official. She became NACA's first Black supervisor, a position of authority that was almost unthinkable in the Jim Crow South.

Mary Jackson forged a different path. After starting in the West Area, she was assigned to work with an engineer named Kazimierz Czarnecki on the East Side of campus, a predominantly white area. One day, humiliated after being unable to find the "colored" bathroom, she vented her frustration to Czarnecki. Instead of offering sympathy, he saw her potential and offered her a challenge: "Why don't you become an engineer?" To do so, she needed graduate-level math and physics courses—courses that were only offered at the all-white Hampton High School. Mary had to petition the city of Hampton for special permission to attend night classes alongside white students. She won, got her credentials, and in 1958, became NASA's first Black female engineer, breaking a barrier not just within the laboratory, but in the segregated educational system of Virginia itself.

The Go-No-Go: The Woman Who Calculated the Path to the Stars

Key Insight 4

Narrator: While Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson were breaking barriers in supervision and engineering, Katherine Goble—later Johnson—was charting a course to the stars. A mathematical prodigy who started high school at ten, her career was initially sidetracked by marriage and family. But in 1953, she found her way to Langley. Her profound talent for analytic geometry was immediately recognized, and she was quickly pulled from the computing pool into the exclusive, all-male Flight Research Division. This was the inner sanctum, the group tackling the most pressing problems of the dawning space age.

Katherine was assertive and brilliant, refusing to be limited by her gender or race. She asked questions in meetings, demanded to see the reports she was contributing to, and insisted her name be included on them—all unheard-of behaviors for a female "computer." Her work was so critical that when the Space Task Group was formed to put a man into space, she went with it. This led to the pivotal moment of her career with John Glenn's orbital flight. The trust Glenn placed in her—a Black woman from a segregated unit—to be the final human check on the machine's calculations was the ultimate validation. Her mind provided the final "go for launch," securing her place as an indispensable figure in the race to space.

Conclusion

Narrator: The single most important takeaway from Hidden Figures is that the grand narratives of American history are incomplete. The story of the space race—often told as a tale of heroic astronauts and brilliant male engineers—was, in reality, built on the invisible labor and unheralded genius of African American women. They were not on the margins of the story; they were at its very center, performing the calculations that made flight safer, faster, and ultimately, capable of leaving the planet.

The book does more than just add a few missing names to the historical record; it challenges us to fundamentally question who we see as the architects of progress. It leaves us with the profound understanding that behind every great achievement lies a network of hidden figures. Their legacy is a powerful reminder to look past the spotlight, to recognize the quiet, essential work of those in the background, and to ask ourselves: whose contributions are we failing to see today?