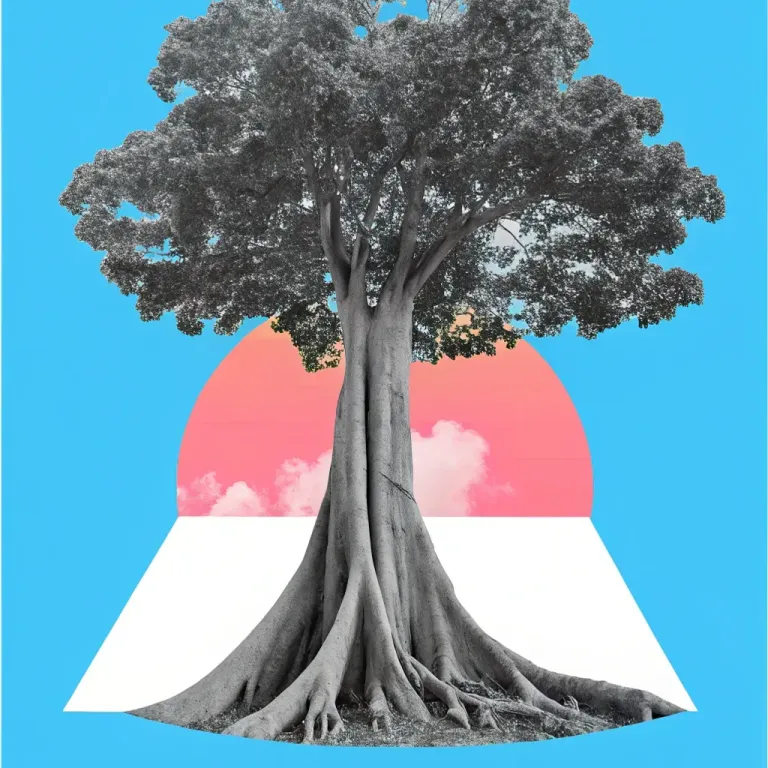

Forest Wisdom: Grow Stronger Together

Podcast by Wired In with Josh and Drew

Discovering How the Forest Is Wired for Intelligence and Healing

Forest Wisdom: Grow Stronger Together

Part 1

Josh: Hey everyone, welcome to the show! Today, we're heading into the forest to explore how trees might be communicating in ways we never thought possible. Drew: Gossiping trees, Josh? Seriously? I mean, picturing trees chatting underground sounds like something out of a fantasy novel, but apparently, that's not far from the truth. Josh: Exactly! We’re talking about Suzanne Simard's incredible book, “Finding the Mother Tree”. It’s part memoir, part groundbreaking research. It really changes how we look at forests. They're not just a bunch of individual trees, but a complex, interconnected network where trees communicate, share resources, and even, in a way, take care of each other. Drew: So, Simard introduces this idea of "Mother Trees" – which, okay, sounds a bit mystical. But these are basically the elder trees of the forest, nurturing the younger ones? They don't have cell phones, obviously, but they're using fungi to share nutrients and information. It’s nature's own version of the internet, right? Josh: It really is. But it's not just about the science. Simard also shares her own story – growing up in a logging family, navigating a career in a male-dominated field, and even dealing with her own health challenges. It's this very personal and human story intertwined with her scientific discoveries that makes the book so compelling. Drew: Okay, so what are we going to dig into today? Are we going to explore how these trees actually "talk" through these underground fungal networks? And then, what does this mean for how we manage our forests? Because I imagine clear-cutting isn't exactly seen as a good thing in this world. And finally, the big question: what can we learn from all this about ourselves and how we connect with each other? Josh: Precisely, Drew! Whether you’re a nature enthusiast, a science lover, or just looking for some food for thought, this episode is for you then. Let's dive in and explore the forest, and maybe even rethink how we connect with each other in our own lives.

The Interconnectedness of Forests

Part 2

Josh: So, Drew, let's dive right in, shall we? The cornerstone of this interconnected world, as Suzanne Simard reveals, hinges on mycorrhizal fungi. These incredible networks are, I mean, they're truly the linchpins of her research. They're like these subterranean threads that bind the entire forest together, quite literally. Without them, the forest dynamics she describes simply wouldn't exist. Drew: Right, they’re like the unsung heroes of the forest, the logistics team running the show while the trees bask in the limelight. But, help me out here, Josh—how exactly do these fungi orchestrate all of this? I get that they're attached to tree roots, but… what are they actually doing down there? Josh: Good question. Mycorrhizal fungi, they form a symbiotic relationship with tree roots. Basically, the fungi expand into the soil, reaching way beyond a tree's immediate root system. Consider them supplementary hands, gathering water and nutrients, like phosphorus and nitrogen, that the tree might not otherwise be able to get on its own. Drew: And in return, the trees cough up carbon, right? Sort of like paying rent for the fungi's services? Josh: Precisely. The fungi acquire the carbon produced during photosynthesis by the trees. But here's the cool part, Drew—it's not just a one-to-one exchange between a tree and its fungi. These networks are extensive, connecting numerous trees, even those of different species. Simard's research demonstrated that the fungi essentially create a decentralized communication system. One tree can "talk" to another—sharing nutrients, sending warnings, and even bolstering young saplings—through these fungal connections. Drew: Wait a minute. Trees chatting with each other underground? Are you saying it's like the forest's version of Slack? I imagine the Mother Trees organizing strategy sessions about who needs carbon the most. Josh: That's not too far off, really! That's the fascinating aspect of Simard's findings. Take her isotope experiments with birch and Douglas-fir, for instance—they were groundbreaking. She labeled carbon in the birch trees and traced its movement through the mycorrhizal network. The birch, flourishing in summer sunlight, transferred some of its carbon to support nearby Douglas-fir trees struggling in the shade. Then, in the fall, as the birch began to decline, the fir trees reciprocated. It's a narrative of mutual aid—not ruthless competition. Drew: So, it completely flips the script on the traditional competition narrative. Instead of "survival of the fittest," it's more along the lines of "survival of the friendliest." But here's my question. Was this cooperation a result of the network "knowing" it was beneficial in the long run, or is it merely… coincidence? Josh: Well, it's less about "intentionality" in the way we think of human decision-making, and more about how ecosystems evolve to maximize survival. The birch and fir had more to gain by cooperating. Birch trees grow rapidly and provide resources when they're abundant, whereas fir trees take longer to develop but are better suited to harsher conditions, like cold winters. Ultimately, the forest as a whole benefits from this diversity and resilience. Drew: Hmm, fascinating. But that kind of cooperation would probably complicate things for us humans, wouldn't it? Forestry practices these days lean pretty heavily on uniformity. If you're trying to maximize timber production, wouldn't you simply plant rows and rows of the same tree? Josh: That’s precisely the issue! Monoculture plantations may generate quick profits, but they come at a significant ecological cost. These simplified systems disrupt the mycorrhizal networks. Without the biodiversity that naturally fosters cooperation and resource-sharing, the forest becomes less resilient. It’s like constructing a house of cards—it won't withstand pests, disease, or climate stress. Drew: And that’s where Simard’s concept of "Mother Trees" comes into play, right? These aren’t just large, old trees—there's something fundamentally different about their role in the ecosystem. Josh: Absolutely. Mother Trees serve as the hubs of these networks, channeling resources to younger or struggling trees, especially seedlings—often their own offspring. Simard even discovered that if a Mother Tree is injured or dying, it prioritizes transferring nutrients to nearby trees, effectively "nurturing" the next generation. Drew: It’s like forest inheritance. These older trees are virtually signing their wills—dividing up resources to give their community the best chance at survival. But here's my skeptical side peeking through. How do we know it’s actually about altruism and not, say, just a lucky fluke of natural resource allocation? Josh: Simard’s isotope studies provide compelling evidence that this is an active process. For instance, when a Mother Tree is stressed—say, from drought—it sends chemical signals through the network that effectively warn nearby trees. These signals enable other trees, particularly young saplings, to adjust their growth or prepare for the stressor. It’s not random resource allocation; there's a clear, observable pattern of prioritization. Drew: OK, but let’s not get too carried away with romanticizing it. Because warning signals aside, it still doesn’t prevent industrial logging from targeting the biggest trees first, right? That’s the double-edged sword I see here. We're taking down the hubs of these ecosystems without truly grasping the long-term consequences. Josh: Exactly! That’s why Simard’s research is so vital—it highlights the critical role these trees play not just for the forest but for biodiversity as a whole. For example, birch-fir cooperation serves as a small-scale model of what’s occurring across diverse species in natural forests. It’s these relationships that create a stable, functioning ecosystem. Drew: So, biodiversity and interconnectedness aren’t simply bonuses—they’re actually survival mechanisms. But it truly makes you think, doesn’t it? If forests have evolved to support one another so intricately, what lessons could we, as humans, glean from that?

Rethinking Forestry Practices

Part 3

Josh: So, understanding how connected forests are naturally leads to rethinking how we manage them. Building on all of this, Drew, we really need to talk about how Suzanne Simard's work challenges traditional forestry practices. These practices, unfortunately, often completely ignore the principles of connectivity and biodiversity. Drew: Oh, you mean the “clear-cut and replace with a single type of tree” approach? You know, if trees could actually complain, they'd have a lot to say about that. Josh: Absolutely! Clear-cutting and monoculture planting are incredibly damaging practices. They’re really geared towards short-term profit, but in the long run, they harm forests in ways most people just don’t realize. Simard’s research shows how these practices destroy the mycorrhizal networks … it's like ripping out the forest's entire communication system, you know? Drew: And no communication means no sharing of resources, which I guess makes the forest incredibly vulnerable, right? Josh: Exactly. Take clear-cutting, for example. When you remove all the trees in an area, you're not just clearing what you see above ground. You’re severing those vast fungal networks below. So, any new saplings planted there lack the support they need. They're basically left to fend for themselves in nutrient-poor soil and are much more susceptible to pests, droughts, and diseases. Drew: Right, it's like throwing someone who can't swim into the deep end. What about monocultures, though? They seem more… organized, I guess. Do they have any advantages? Josh: Well, monocultures might look uniform, but they lack resilience. They strip away the diversity that makes ecosystems thrive. Different tree species have different strengths. Birch, for example, can provide crucial nutrients and shade to neighbors like Douglas firs, especially when they’re stressed. But in monocultures, those relationships just don't exist because the entire ecosystem is artificially simplified. Drew: So, you end up with a forest that looks tidy but is basically defenseless against pests or wildfires. One bug that likes pine, and the whole thing goes up in smoke. Josh: Precisely! Simard often emphasizes that biodiversity is key to resilience. In one of her studies, she showed that birch and fir trees actually exchange nutrients. During the summer, birch trees share carbon with shaded Douglas firs. Then, in autumn, the firs return the favor when the birch trees slow down, isn't it pretty cool? Drew: Okay, I see that nature has this whole “teamwork makes the dream work” thing figured out. But where does that leave the forestry industry? Are they just going to say, “Oh well, ecosystems are more important than money, let's change everything?” How do we actually push for change in such an established system? Josh: That's the challenge, right? It's a clash between ecology and economics. But Simard doesn’t just criticize existing practices … she also offers solutions. One important shift she suggests is protecting the "Mother Trees." Drew: Ah, the VIPs of the forest. The biggest and most connected trees, right? The ones logging companies probably target first? Josh: Yes, often the oldest and largest trees. But they’re so much more than timber. Mother Trees act as hubs in the network, distributing resources and supporting seedlings, especially their offspring. When a Mother Tree is cut down, the repercussions are felt throughout the forest. By preserving them, we’re not just saving a single tree. We're maintaining the entire community it supports. Drew: It makes you wonder, doesn't it? If we knew these old trees were running a neighborhood watch program for the forest, would we still be so quick to cut them down? Josh: That is Simard’s point exactly! That we need to see forests as living systems, not just resources to be exploited. And this perspective closely aligns with Indigenous ecological knowledge. Indigenous communities have long understood the importance of selective harvesting and balance. Their practices reflect Simard’s scientific findings, for example, leaving seed-bearing trees intact or ensuring forest diversity. Drew: So, it's not just tradition; it's wisdom based on generations of observation. Modern forestry could definitely learn a lot about sustainability from those methods. Has there been any real effort to incorporate Indigenous knowledge into forestry policy? Josh: Slowly, yes, but there's still a long way to go. Some regions are starting to recognize the ecological benefits of these practices, especially as we realize how closely forest health is tied to climate change. Simard makes a compelling case for sustainable forestry, not just for the sake of biodiversity, but because forests play a critical role in carbon sequestration. Protect the Mother Trees, preserve the networks, and we boost our fight against climate change. Drew: That sounds great, but, you know, even with all this data, convincing industries and policymakers to adopt new methods … especially ones that might cost more initially … is tough. What's the incentive? Josh: It is a challenge, but one incentive could be long-term economic benefits. Forests managed sustainably are less prone to catastrophic events like wildfires or pest outbreaks, which can wipe out entire plantations. Plus, healthy, biodiverse forests continue to provide ecosystem services … like clean air and water, carbon storage, and soil stability … that benefit us all. Drew: So, it’s basically an investment in resilience. Spend a little more now to avoid a disaster later. The hard part is convincing people to think beyond the next few financial quarters. Josh: Exactly! And that's where science, policy, and public engagement come together. Simard’s research provides the science, and now it’s up to us to translate those findings into action, bridging the gap between ecological principles and forestry practices. Drew: Well, if there's one thing to take away from this, it's that forests aren't just resources to harvest … they're communities to preserve. Learning to manage them with their interconnectedness in mind might be our best bet for balancing profit and sustainability.

Lessons for Human Resilience and Community

Part 4

Josh: Absolutely, Drew. It's more than just forestry; it's about resilience, interconnectedness, and how we navigate life's challenges together. Drew: Exactly! So, Josh, the real gold here isn’t just in forest management techniques, is it? It’s the profound lessons forests offer about resilience and community. Josh: Precisely! Simard's work beautifully illustrates how mutual support and collaboration are fundamental to survival, whether we're discussing trees or people. Her journey, overcoming professional obstacles and navigating personal loss, really drives this point home. Drew: Okay, so let's dive in. Let's start with this core concept: collaboration as a resilience strategy. What can trees actually teach us about teamwork? Josh: Well, forests show us that strength flourishes in diversity and connectivity. Take Simard's research on birch and fir trees. They don't just coexist; they actively support each other via mycorrhizal networks. Birches, for example, share excess carbon with firs during summer, when the firs are struggling, and the firs reciprocate in the autumn, when conditions improve for them. Drew: So, it's a seasonal “quid pro quo,” right? But beyond just being nice, that collaboration is actually boosting the overall resilience of the forest, not just fostering competition. Josh: Precisely! That reciprocity ensures that resources flow where they're needed most, even under challenging conditions. Simard draws a direct line to human societies, arguing that community resilience—whether ecological or human—hinges on cooperative networks. When people join forces–sharing resources, offering support, or mentoring others–they create stronger, more adaptable systems. Drew: It's a powerful idea, Josh. But look at how we often react to adversity, especially in our modern world. It feels like we’re stuck in "survival of the fittest" mode. Everyone’s scrambling for resources; it’s almost the polar opposite of what those trees are doing. Josh: I hear you. And Simard’s personal experience highlights that. She encountered significant opposition in her field, being a woman in a male-dominated industry and proposing ideas that went against the traditional forestry paradigms. She had to build her own network of collaborators to advance her research. In the same way that trees support surrounding seedlings, Simard’s human network - colleagues, friends, and family - helped her weather those challenges. Drew: Let me jump in with a specific example of that resistance. Remember the story where she presented her findings, and the industry guys dismissed her, saying, "You just don't get it"? That’s so frustrating! And yet, she persevered. That kind of resilience, pushing forward when the system is rigged against you, is truly impressive. Josh: Exactly. And beyond the professional resistance, Simard also grappled with balancing personal and professional responsibilities. I remember one story where she was presenting crucial research while managing the demands of being a nursing mother, juggling science and childcare under pressure. These moments aren't just anecdotes; they symbolize the multifaceted roles and challenges many people face. Drew: It's a powerful reminder that resilience isn't just about enduring hardship. It's about pulling strength from those connections, from those support systems. And that leads to an interesting point, Josh - this concept of interdependence itself. You mentioned that Simard found solace observing the forest after her brother's death. What was it about the connections between trees that helped her process her grief? Josh: That part of her story is deeply moving. After her brother passed away, she found solace in the forest, noticing parallels between her grief and the tree lifecycle. She saw how Mother Trees prioritize their kin, sharing resources even as they weaken. This showed her how life involves giving, supporting, and passing on strength. For Simard, it was comforting to realize that connections endure even through loss, both in forests and in human relationships. Drew: So, even when something appears to be ending—like an old tree dying—it’s not really over. It’s perpetuating a cycle of life and growth through those connections. There’s something beautifully hopeful in that, isn't there? Josh: Absolutely, Drew. And that hope extends to Simard's vision for stronger communities. She emphasizes that relationships are fundamental to resilience – not just for forests, but for us as well. When we share resources, listen, and collaborate, we become more adaptable. Her message is clear: thriving isn’t a solo act, whether you’re talking about trees or societies. It’s a communal endeavor. Drew: And that’s the profound lesson we can take from the wisdom of forests. It’s not just about better forest management or studying fungi. It’s about applying these insights to how we conduct our lives – building support networks, cultivating diversity, and realizing that we truly are stronger together.

Conclusion

Part 5

Josh: So, today we’ve been diving deep into Suzanne Simard's research and her own incredible story. We've “really” uncovered this hidden, amazing web of life that connects trees, and the “really” profound lessons it offers us. From these mycorrhizal networks that allow trees to, like, actually communicate and share resources, to the crucial role of these Mother Trees in keeping the forest strong, we’ve totally redefined what it means to see forests as these interconnected communities. Drew: Right, and it's not just about the trees. We’ve also zoomed out to see the bigger picture, haven't we? How this groundbreaking science challenges how we do forestry, why biodiversity is so important, and even how we can learn from it in our own lives. I mean, whether it's trees supporting each other or humans finding strength in community, the parallels are, well, they're pretty obvious. Josh: Exactly! Simard's work is a “real” call to action. It's not just about protecting forests, but “really” rethinking how we connect with the world and, you know, each other. If we can learn anything from the forests, it’s that survival isn’t about going it alone. It’s about “really” embracing our connections, nurturing diversity, and working together to tackle whatever comes our way. Drew: So, what’s the bottom line here? Whether it’s planting a tree, pushing for sustainable forestry, or just recognizing the power of teamwork in your own life, every little bit helps build a stronger, more resilient system. Forests thrive because they’re interdependent. Maybe, just maybe, it’s time we did the same. Josh: Yeah! Thanks for exploring the wisdom of the forest with us today. Let’s take these lessons with us and grow stronger, together. Drew: Absolutely. Until next time, remember—whether you’re a towering oak or just a seedling in the shade, your connections are what matter. Keep growing, everyone.