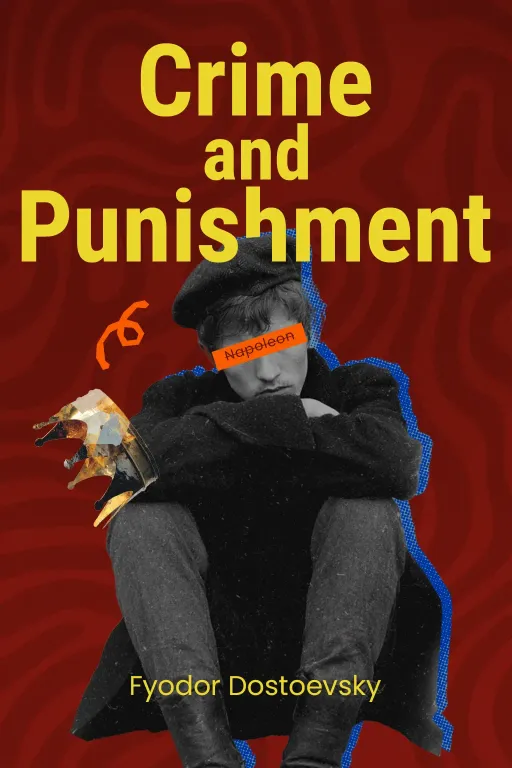

Crime and Punishment

10 minIntroduction

Narrator: What if you believed you were so intelligent, so exceptional, that the normal rules of morality simply didn't apply to you? What if you convinced yourself that for the greater good, you had the right—even the duty—to commit murder? This is the terrifying proposition at the heart of the story of Rodion Raskolnikov, an impoverished and brilliant former student living in the squalor of 19th-century St. Petersburg. Consumed by his intellectual pride and desperate poverty, he formulates a theory that divides humanity into two categories: the ordinary, who must live in obedience, and the extraordinary, who have an inner right to transgress any law to achieve a higher purpose. In his seminal work, Crime and Punishment, Fyodor Dostoevsky takes us on a harrowing journey into the mind of a man who dares to test this theory, only to discover that the true punishment for a crime is not found in a prison cell, but in the inescapable prison of one's own conscience.

The 'Extraordinary Man' Theory

Key Insight 1

Narrator: At its core, the novel is driven by Raskolnikov's radical philosophical idea. He argues that certain "extraordinary" individuals, like Napoleon, are not bound by conventional morality. For the sake of a great idea or a new word for humanity, they are permitted to "step over" obstacles, even if that obstacle is another human life. Raskolnikov, seeing himself as one of these extraordinary men, identifies his target: Alyona Ivanovna, a greedy and despised old pawnbroker. He rationalizes that her death would be a net positive for society. He could use her stolen money to rescue his beloved sister, Dounia, from a loveless marriage of convenience and to launch his own brilliant career, ultimately benefiting all of humanity.

This intellectual justification fuels his meticulous planning. Yet, Dostoevsky masterfully shows the cracks in his resolve. Raskolnikov is plagued by a feverish dream in which, as a child, he witnesses a group of drunken peasants brutally beat a mare to death. He wakes up in horror, renouncing his "accursed dream" of murder. But fate, or coincidence, seems to push him forward. He overhears a conversation confirming the pawnbroker will be alone, solidifying his resolve. He commits the act, killing Alyona with an axe, but in a moment of panicked chaos, he is forced to also murder her gentle sister, Lizaveta, who stumbles upon the scene. The "clean," philosophical crime he envisioned instantly becomes a bloody, senseless, and dual tragedy.

The Punishment Before the Prison

Key Insight 2

Narrator: Raskolnikov quickly learns that the true punishment for his crime begins the moment the axe falls. It is not a legal sentence but a profound psychological and spiritual decay. Immediately following the murders, he is consumed not by a sense of triumph, but by a debilitating fever, paranoia, and a complete disconnect from reality. His intellectual theory offers no comfort against the visceral horror of his actions. He hides the stolen goods clumsily, driven by panic rather than the cold logic he prided himself on.

His punishment is one of isolation. He can no longer connect with anyone, not even his loyal friend Razumihin or his own family. Every conversation is a potential trap; every glance is an accusation. This is powerfully illustrated when he is summoned to the police station for a minor debt. The ordinary setting becomes a torture chamber for his guilty mind, and he faints when the officers casually discuss the recent murders, nearly confessing through his sheer physical and mental collapse. Dostoevsky makes it clear: the crime itself was the first step of the punishment, severing Raskolnikov from the human community and trapping him in the solitary confinement of his own mind.

The Psychological Duel

Key Insight 3

Narrator: Raskolnikov's intellectual pride meets its match in the form of Porfiry Petrovich, the brilliant and unconventional investigating magistrate. Porfiry represents a different kind of intelligence—not one of abstract theory, but of deep psychological intuition. He suspects Raskolnikov almost immediately but has no concrete evidence. Instead of a direct confrontation, Porfiry engages Raskolnikov in a series of tense, psychological duels.

During their meetings, Porfiry circles his prey with seemingly casual conversation, discussing Raskolnikov's own published article on the "extraordinary man" theory. He probes, flatters, and provokes, all while maintaining a friendly demeanor that only amplifies the tension. Porfiry understands his opponent perfectly. He tells Raskolnikov that a guilty man is psychologically unable to escape. "He will keep circling around me, getting closer and closer," Porfiry explains, confident that Raskolnikov's own mind will eventually betray him. This cat-and-mouse game becomes a central battleground of the novel, a clash not of evidence, but of intellect and willpower, pushing Raskolnikov ever closer to the breaking point.

The Two Paths of Transgression

Key Insight 4

Narrator: As Raskolnikov spirals, he is confronted by two characters who represent the possible outcomes of his transgression: Sonia Marmeladova and Arkady Svidrigailov. Both have "stepped over" moral lines, but they embody opposing paths.

Sonia, the daughter of a tragic drunkard, has been forced into prostitution to save her family from starvation. She is a sinner in the eyes of society, yet she possesses a profound and unwavering Christian faith. Raskolnikov is drawn to her, sensing a fellow transgressor. In a pivotal scene, he demands she read him the biblical story of Lazarus, the man resurrected from the dead. In Sonia, he sees the possibility of his own spiritual rebirth through faith and humility.

Svidrigailov, a wealthy and depraved landowner, represents the dark alternative. He is a man who has committed heinous acts but feels no guilt, only a bored and sensual emptiness. He overhears Raskolnikov's confession to Sonia and embodies the "extraordinary man" without a conscience. Yet, his life is a void. Haunted by ghosts and unable to find meaning in his debauchery, Svidrigailov ultimately commits suicide, demonstrating that a life without moral boundaries leads not to freedom, but to nothingness.

Confession as Liberation

Key Insight 5

Narrator: Torn between Sonia's path of redemption and Svidrigailov's path of nihilism, Raskolnikov realizes he cannot live with his secret. The psychological pressure from Porfiry and the weight of his own guilt become unbearable. The true turning point comes when he confesses everything to Sonia. He expects her judgment, but instead, she responds with overwhelming compassion. "What have you done to yourself!" she cries, embracing him and promising to follow him to his punishment. It is her love, not his logic, that begins to heal him.

Following her guidance, he goes to the public square, kneels, and kisses the "defiled earth," a symbolic act of accepting his sin against humanity. He then walks into the police station and, in a quiet, exhausted voice, confesses: "It was I killed the old pawnbroker woman and her sister Lizaveta with an axe and robbed them." This act is not a defeat but a liberation—the first step away from the prison of his pride and toward the possibility of atonement.

Redemption Through Suffering

Key Insight 6

Narrator: The novel's epilogue finds Raskolnikov in a Siberian prison camp. Initially, he remains proud and unrepentant, despising the other convicts and feeling no remorse for his crime, only for his failure. He is still trapped in his intellectual theory. The true transformation is slow and arduous. It is Sonia, who has followed him to Siberia, who facilitates his rebirth. Her unwavering, selfless love slowly chips away at his hardened heart.

His final awakening comes after an illness, in a dream of a world infected by a plague of nihilistic ideas, where everyone believes their own truth is absolute, leading to chaos and self-destruction. He finally understands the destructive nature of his own theory. Waking from the dream, he sees Sonia and, for the first time, weeps and embraces her. In that moment, his intellectual pride is replaced by love. He picks up the New Testament she had given him, signaling the beginning of a new story: the gradual renewal of a man, his slow passage from one world into another.

Conclusion

Narrator: The single most important takeaway from Crime and Punishment is that the laws of the human heart and conscience are far more powerful and inescapable than any legal code or intellectual theory. Dostoevsky argues that a crime against another person is fundamentally a crime against oneself, leading to an unbearable spiritual isolation that no rationalization can cure.

The book's most challenging idea is its profound critique of pure reason divorced from morality and compassion. It serves as a timeless warning against the arrogance of believing that a great intellect can justify monstrous acts. Dostoevsky leaves us with a question that resonates to this day: Where does true freedom lie? Is it in the power to transgress boundaries, or in the humble acceptance of our shared humanity and the redemptive power of love and suffering?