Beyond the Screen: How Digital Tools Shape Our Real-World Connection.

Golden Hook & Introduction

SECTION

Nova: Sometimes, the very tools designed to bring us closer actually push us further apart. It’s a paradox that sits right at the heart of our modern lives.

Atlas: Oh man, that hits home for so many people. We scroll and tap, feeling connected, yet sometimes it feels like we're just shouting into the void. What exactly are we talking about today, Nova?

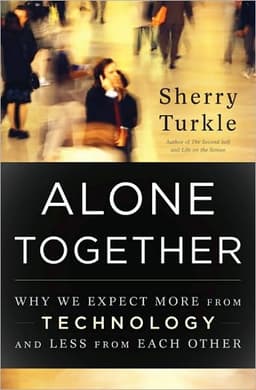

Nova: Today, we’re dissecting, and we’re drawing heavily from two seminal works that profoundly shifted how we understand this tension. First, Sherry Turkle’s, a groundbreaking exploration of how technology redefines human relationships. And second, Robert D. Putnam’s, a widely acclaimed study on the decline of social capital. Turkle, a psychologist, has spent decades meticulously observing our digital lives, while Putnam’s work, which looked at community engagement across decades, profoundly shifted how we understood the fabric of society.

Atlas: That’s a powerful combination. So, are we saying these brilliant minds are telling us our phones are inherently bad, or is there more nuance to it? Because I imagine a lot of our listeners, especially those ethically exploring AI or integrating smart homes, are thinking, "But these tools are."

Nova: That’s the exact tension we need to explore, Atlas. It's rarely about good or bad, but about impact and intention. We often focus on the utility of digital tools, overlooking their profound impact on our social fabric. Our online interactions can subtly reshape our real-world relationships and our very sense of community.

The Paradox of Digital Connection: Alone Together

SECTION

Nova: Let’s start with Turkle’s core argument: we expect more from technology and less from each other. She argues that we’ve become accustomed to a kind of "edited" connectivity. Think about it: a text, an email, a carefully curated social media post. These allow us to present ourselves exactly as we want to be seen, to control the pacing of our responses, to avoid the messy, unpredictable nature of real-time, face-to-face conversation.

Atlas: I can definitely relate to that. It’s like when you’re crafting the perfect response to a message, taking five minutes to write two sentences. It feels efficient, but I see what you mean about avoiding the messiness.

Nova: Exactly. Turkle observed teenagers who preferred texting to talking on the phone, let alone meeting in person. They felt more in control, less vulnerable. The cause here is the constant digital access, the process is this preference for a curated online performance, and the outcome is a diminished capacity for deep empathy and patience in real-time conversation. She vividly describes scenes: families at dinner, each member absorbed in their own device, physically present but emotionally absent. Or business meetings where everyone is simultaneously checking emails under the table.

Atlas: Wow. That's actually really profound. It makes me wonder, though, isn't there a risk of romanticizing the past? Were all face-to-face interactions always deep and meaningful, or were some just awkward silences we've now found a way to avoid?

Nova: That's a fair point, and Turkle isn't arguing for a return to some idyllic past. She's highlighting a shift in our psychological landscape. The cost isn't just awkward silences; it's the erosion of solitude, the fear of missing out, and a constant performance anxiety. We're always "on call," always available, yet often feel more alone than ever. It's a paradox: we use technology to avoid the discomforts of solitude, only to find ourselves isolated in a crowd. We're connected to a network, but disconnected from ourselves and from the full, unedited presence of others.

Atlas: So basically you’re saying we're trading depth for breadth, and in doing so, we're losing some essential human skills for navigating complex, unscripted interactions? That sounds rough.

Nova: Precisely. We're becoming accustomed to having an audience, to performing our lives, rather than simply living them. This constant self-editing, this desire for perfect presentation, makes us less willing to engage in the spontaneous, sometimes challenging, but ultimately more rewarding interactions that build true intimacy and connection.

Rebuilding Social Capital: Digital Tools and Community Bonds

SECTION

Nova: And that naturally leads us to the second key idea we need to talk about, which often acts as a counterpoint to what we just discussed: how these individual shifts aggregate into broader societal changes, impacting our community bonds and what Robert D. Putnam famously called "social capital."

Atlas: Oh, I've heard of. That's the book about how people stopped joining bowling leagues and other clubs, right?

Nova: Exactly. Putnam's classic work examines the decline of social capital in America – that's the networks of relationships among people who live and work in a particular society, enabling that society to function effectively. It’s about trust, reciprocity, and shared norms that arise from face-to-face interaction and civic engagement. While not directly about digital tools, it provides a powerful framework for understanding the importance of community bonds that technology can either support or erode.

Atlas: So, if Turkle is talking about individual isolation, Putnam is looking at the collective impact. But wait, couldn't digital tools actually social capital? Think about online communities for niche hobbies, or local Facebook groups that help neighbors connect. I imagine a lot of our listeners who are exploring smart home integration might be thinking about how technology can foster local connections, not just erode them.

Nova: That’s a fantastic point, and it highlights the nuance. Digital tools absolutely build social capital, but often, the way we use them doesn't. Consider a neighborhood Facebook group. The cause is a desire for local connection, the process is online discussion. But the outcome can sometimes be a replacement of real-world engagement. People might discuss local issues online, feel informed, but then attendance at actual town hall meetings or volunteer events declines. We mistake passive consumption of information for active participation. It’s like knowing all your neighbors’ updates through social media, but never actually sharing a cup of sugar or helping them move a couch.

Atlas: So, it's the difference between "liking" a post about a community garden and actually showing up to plant something. I see. It's that shift from active contribution to passive observation.

Nova: Precisely. Putnam's concern was about the decline of bridge-building social capital – connections across diverse groups – and bonding social capital – strong ties within homogeneous groups. Digital tools, while great for bonding within niche online communities, can sometimes make it easier to stay within our echo chambers, rather than fostering broader civic engagement.

Atlas: That makes me wonder, how can we use these tools more intentionally? For someone who cares about technology shaping humanity and wants to apply new tech for practical living, what’s the practical takeaway here? Are we doomed to be digitally connected but deeply disconnected, both individually and communally?

Synthesis & Takeaways

SECTION

Nova: Not at all, Atlas. That's the crucial insight. Nova's take, and ours, is that thoughtful engagement with digital tools means understanding their social consequences, ensuring they enhance, rather than diminish, genuine human connection and community. It comes down to intentionality.

Atlas: Okay, so how can you intentionally use digital tools to foster deeper, more meaningful connections in your life, rather than simply accumulating superficial interactions? That’s the deep question, isn’t it?

Nova: It absolutely is. One practical step is to design "digital sabbaths" – periods where you intentionally disconnect. It could be an hour a day, a day a week, or even just leaving your phone in another room during meals. This reclaims your attention and creates space for real-world interactions. Another is to prioritize real-world meetups. Use digital tools as a bridge to connection, not the destination. If you connect with someone online, make the effort to meet them in person. If you see a local event on social media, to it.

Atlas: That’s a great way to put it – using it as a bridge, not the destination. It reminds me of the idea of grounding future trends in past innovations. We’re not reinventing human connection; we’re just finding new pathways, and we have to be mindful of where those pathways lead.

Nova: Exactly. True connection requires presence and vulnerability. Technology can either facilitate or hinder that, depending on our choices. It's about designing our digital lives to serve our human needs, not the other way around. It's a constant, mindful effort to ensure our tools amplify our humanity, rather than diminish it. So, my challenge to our listeners this week: observe your own digital habits. Where are you using digital tools as a destination, and where could you use them as a bridge?

Atlas: That’s such a hopeful way to look at it. It puts the power back in our hands.

Nova: Absolutely. It’s about being the conscious architect of your connected life.

Nova: This is Aibrary. Congratulations on your growth!