Ethical Frameworks for Environmental Stewardship and Innovation

Golden Hook & Introduction

SECTION

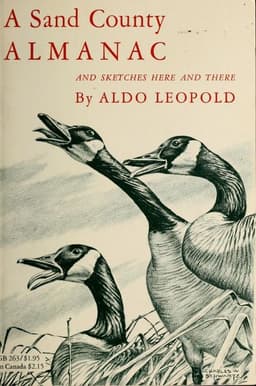

Nova: Alright, Atlas, quick challenge for you. We're talking about foundational environmental ethics today. Give me a five-word review of Aldo Leopold's "A Sand County Almanac."

Atlas: Oh, a five-word review? Hmm. "Nature: not just property, but family."

Nova: Ooh, I like that! "Not just property, but family." That perfectly captures the essence of what Aldo Leopold was trying to shift in our collective consciousness with his groundbreaking book, "A Sand County Almanac."

Atlas: Yeah, it’s a total game-changer for how you view the world. And speaking of game-changers, we also have Rachel Carson's "Silent Spring" on the table today. If Leopold gave us the philosophical blueprint, Carson gave us the urgent, scientific wake-up call. Her meticulous research didn't just expose the devastating effects of pesticides; it pretty much birthed the modern environmental movement and directly led to policy changes.

Nova: Absolutely. These two books, published decades apart, really form the ethical compass for anyone trying to navigate our relationship with the natural world. They challenge us to think beyond ourselves, beyond the immediate, and consider our profound moral responsibility.

Atlas: And for our listeners, the analytical architects and ethical explorers out there, these aren't just historical texts. They're living frameworks for understanding today's environmental debates.

The Land Ethic: Expanding Our Moral Circle

SECTION

Nova: So, Atlas, you hit on it with your five-word review: "Nature: not just property, but family." Leopold, a forester and conservationist, saw the land not as an endless resource to be exploited, but as a living system, a community to which we belong.

Atlas: It’s easy to say, "We should respect nature," but what does that actually look like in practice? Especially for someone in a high-stakes industry, where land is often seen purely as an asset for development or extraction. How does this 'land ethic' even begin to apply?

Nova: That's the crux of it, isn't it? Leopold wasn't just waxing poetic. He was a man of the land, working in the field, observing the consequences of our actions. His 'land ethic' emerged from that direct experience. He saw that our ethical codes had evolved from individuals to society, but they stopped short at the boundary of the natural world. He argued we needed to expand our moral circle to include soils, waters, plants, and animals—the 'land' collectively.

Atlas: So he's saying our ethics are incomplete if they only focus on human-to-human interactions? That's a pretty radical idea, even now.

Nova: Exactly. He famously wrote about seeing a wolf die, shot by his group, and witnessing "a fierce green fire dying in her eyes." That moment, for him, was an epiphany. He’d always thought killing wolves was good for deer, good for the mountain. But in that instant, he realized the wolf wasn't just a competitor for deer; it was an integral part of a complex, interconnected system. Removing the wolf had cascading, unforeseen effects on the entire ecosystem.

Atlas: Wow, so it’s not just about animal welfare, it’s about understanding the interconnectedness of everything. That's a powerful image: the "fierce green fire." It makes you realize how much we miss when we only see parts of a system.

Nova: It's about seeing the land as a "biotic pyramid," not just a collection of resources. Humans are part of that pyramid, not at the top, dictating terms. A land ethic, for Leopold, changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for fellow members, and also respect for the community as such. This isn't just about being "nice" to a tree; it's about recognizing our fundamental reliance on a healthy, functioning ecosystem.

Atlas: That completely reframes the conversation. Instead of "what can we take from nature?", it's "how do we participate responsibly within this intricate web?" It's a shift from extraction to integration. But for someone driven by measurable results, how do you measure "respect for the land-community"? That sounds a bit abstract for a quarterly report.

Nova: That's where the analytical mind comes in. It's about translating that ethical principle into concrete goals. It’s about understanding ecological health indicators, biodiversity metrics, sustainable resource management—all of which stem from that core ethical stance. If we genuinely believe we are members of the land community, our actions naturally align with its long-term health. It’s a foundational shift that underpins all sustainable development.

Silent Spring's Echo: Unveiling Unseen Harms

SECTION

Nova: And that understanding of interconnectedness, of unseen impacts, leads us perfectly to Rachel Carson. If Leopold gave us the philosophical lens, Carson gave us the scientific microscope, revealing the immediate and devastating consequences of ignoring that interconnectedness.

Atlas: Her work is legendary, "Silent Spring." But for those who might only know the title, what exactly did she uncover that was so earth-shattering?

Nova: Carson, a marine biologist, was meticulous. She wasn't an activist in the traditional sense; she was a scientist driven by evidence. She documented how widespread use of synthetic pesticides, particularly DDT, wasn't just killing pests. It was accumulating in the food chain, poisoning birds, fish, and eventually humans. She painted a vivid, chilling picture of a future where springs would be silent, devoid of birdsong, because of these chemical assaults.

Atlas: So it wasn't just about the direct application of a chemical, but the ripple effect, the way it moved through the environment and impacted species far removed from the initial target. That sounds like a modern-day supply chain problem, but for ecosystems.

Nova: Precisely. She exposed the hubris of human intervention—the idea that we could simply engineer nature without consequence. Her work showed that these chemicals, invisible to the naked eye after application, were anything but harmless. They were insidiously disrupting ecological balance, causing cancer, birth defects, and widespread environmental degradation.

Atlas: That's incredible—how one person, through rigorous scientific investigation, could uncover something so profound and hidden. For an analytical mind, it highlights the power of deep investigation. But how do we apply that lesson today? We have so many complex innovations, from AI to new materials. How do we spot the "silent harms" in those, before they become a "silent spring" for something else?

Nova: That's the enduring legacy of Carson. She taught us to ask deeper questions, beyond the immediate utility. "What are the long-term, systemic impacts?" "Who or what else is affected?" It's about foresight, about applying a precautionary principle. It means rigorous environmental impact assessments, continuous monitoring, and fostering a culture where scientific integrity isn't sidelined by profit or convenience. It’s about being perpetually curious about the unseen.

Atlas: So, it's not just about regulating chemicals, it's about a mindset of anticipating unintended consequences across all innovation. How would Carson's approach translate to, say, the digital world? Could there be "digital DDTs" or "silent springs" for our attention spans or mental well-being that we're only just beginning to see?

Nova: Absolutely. Her work compels us to look harder, to apply that same analytical rigor to new frontiers. It's about understanding the full lifecycle of a product or technology, from its raw materials to its disposal, and its impact on every living system. Both Leopold and Carson, in their distinct ways, are calling us to a higher standard of ethical intelligence.

Synthesis & Takeaways

SECTION

Nova: So, when we look at Leopold's land ethic and Carson's "Silent Spring," we see two sides of the same coin, don't we? One gives us the profound philosophical framework for belonging, and the other gives us the urgent scientific imperative for caution and accountability.

Atlas: They really do. Leopold makes you question your place in the world, shifting from a mindset of dominion to one of community. And Carson then gives you the tools, or at least the inspiration, to meticulously uncover where we've gone wrong when we've forgotten that community.

Nova: Exactly. They both demand that we expand our moral consideration beyond ourselves. They provide that crucial ethical compass for anyone wanting to engage with environmental stewardship and innovation in a meaningful way. It's not enough to just create; we must create responsibly, with deep foresight and a profound sense of interconnectedness.

Atlas: And for our listeners, the analytical architects and driven achievers, this isn't just about abstract ethics. It's about translating those principles into measurable, concrete goals for sustainable development. It's about using your sharp intellect to identify those underlying ethical principles in any environmental debate, and then applying them to build a better, more sustainable future.

Nova: It’s about asking: how can your analytical skills help translate abstract ethical principles into concrete, measurable goals for sustainable development? That's the challenge these two giants laid out for us.

Atlas: What's one area in your life, personal or professional, where you can apply a deeper ethical lens and uncover a "silent harm" or foster a greater sense of "land community"?

Nova: We invite you to reflect on that question.

Atlas: This is Aibrary. Congratulations on your growth!