Facebook's Mess: Can We Fix It?

Podcast by Wired In with Josh and Drew

Waking Up to the Facebook Catastrophe

Facebook's Mess: Can We Fix It?

Part 1

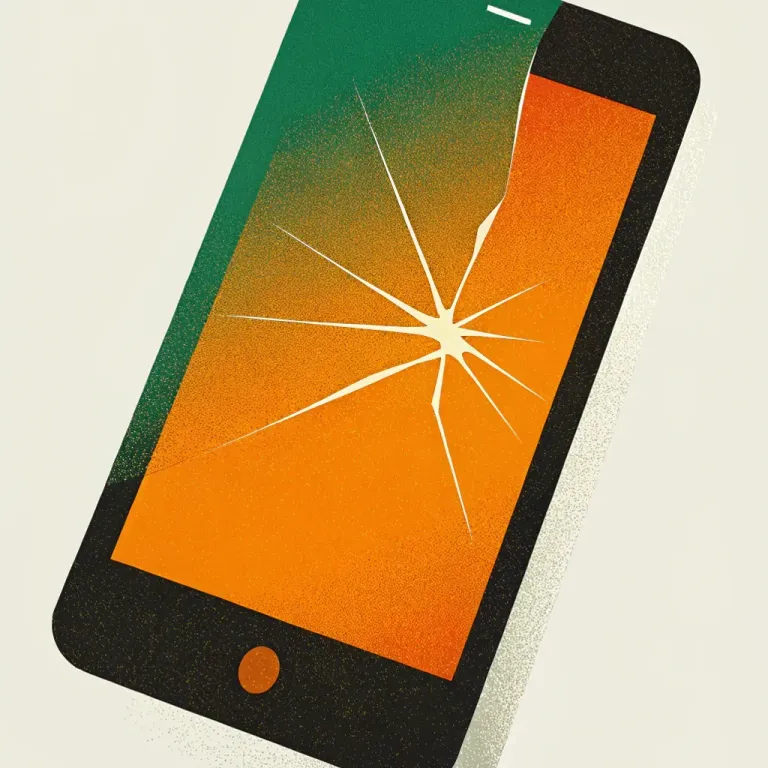

Josh: Hey everyone, welcome back to the podcast! Today, we're diving into a topic that demands answers, not just questions. Imagine a platform that promised to connect the world, but instead became one of the most divisive forces we've ever seen. What happened? Drew: Let me guess, “Facebook happened” is the punchline, right? But seriously, we're tackling Roger McNamee's book, “Zucked: Waking Up to the Facebook Catastrophe”. It's as explosive as the title suggests. Josh: Exactly. McNamee's story is particularly interesting because he wasn't just some bystander. He was actually one of Facebook's early advisors, a true believer. But over time, his optimism just… faded. His insider perspective really paints a picture of how a tech giant, once full of potential, morphed into a global problem factory, amplifying disinformation, eroding trust, and, you know, maybe even threatening democracy. Drew: So, it's basically a tech-age Frankenstein story, then. We created this social media monster, and now it's running wild. But hey, it's a nuanced Frankenstein. McNamee walks us through the history, his own realizations, and offers some pretty sharp critiques of Silicon Valley's often toxic culture. Josh: Right. We're going to break this down into three parts today. First, we’ll look at Facebook's evolution – from its idealistic dorm-room beginnings to its kind of unsettling current state. What exactly happens when "move fast and break things" becomes more than just a cute motto? Drew: Spoiler alert: you might break democracy, apparently. Josh: Yes. Then, we'll get into the ripple effects on society – how it's sowing division, fueling disinformation, and even inciting violence in some parts of the world. Drew: And finally, the big one: accountability. How do we even begin to fix this mess? McNamee argues for strong regulations and what he calls “humane technology,” though I’m sure we'll find plenty to unpack there. Josh: The stakes are incredibly high, so let's get into exactly how we got here and what it might take to get us back on track.

Facebook's Evolution and Ethical Failures

Part 2

Josh: So, that takes us right back to the beginning, to Facebook’s origins. Let’s dive into Mark Zuckerberg’s early vision and see how it blew up into this global phenomenon. It all kicked off in Harvard's dorms, remember? Zuckerberg cooked up Facemash back in 2003. The site basically let students compare and rate each other’s photos... without their permission, I should add. It went viral, racking up, like, 22,000 views in just hours before they shut it down. And not because people didn't like it! Drew: Facemash… what a start, huh? Talk about raising a moral red flag! Can you imagine being one of those students and just randomly finding out your face was trending on some site you never even signed up for? Charming! But seriously, doesn't that feel like a preview of some of Facebook's, shall we say, less-than-ethical practices? Misusing personal data seems to have been in Zuckerberg's DNA from day one. Josh: Exactly. That's why it's so interesting to look at Facebook’s early days. It's all there in the code! Sure, Facemash ticked off the student body, but it also showed Zuckerberg two really important things: the insane power of online social interaction, and the potential to scale up, fast. So, just a few months later, boom, TheFacebook launched in 2004, but only for Harvard students at first. That exclusivity? Genius. It created buzz and this feeling of belonging. And the key? Real profile identities. It gave the platform a level of authenticity and trust that other platforms at the time, like MySpace and Friendster, just didn't have. Drew: Okay, but let’s not pretend that “authenticity and trust” didn’t come with strings attached. Real identities meant real data—names, locations, interests—and Facebook was sitting on all of it. The thing is, even though TheFacebook probably felt like this exclusive club for Ivy League students, it was really setting the stage for Zuckerberg’s grand plan. And then by 2005, they dropped the "The," opened it up to the world, and suddenly it wasn’t just a social network. It was a vision for a new, globally connected world. Josh: Yeah, and for a while, it really felt like that vision was working. People loved how simple it was: a place to connect with friends, share what you're up to, and just feel seen. But this is where things started to change. When Sean Parker came on board as president and Peter Thiel invested, suddenly Facebook wasn’t just about connecting people anymore. The company's whole "Move fast and break things" mantra became the rule, prioritizing growth no matter what it broke. Drew: Let's unpack that "Move fast and break things" motto for a second. Sounds pretty cool, right? Like something straight out of a Silicon Valley movie. But, let's be honest here, it was corporate code for "cut corners, and apologize later." Rushing for growth at all costs might have worked in Silicon Valley's bubble, but once Facebook had, millions, and then billions, of users, there was bound to be damage. And no one thought, "Maybe we should slow down?" It's like flooring a Ferrari through a school zone! Josh: That whole rapid-growth thing really paved the way for some major problems later on. Take monetization, for example. When Facebook jumped into targeted advertising, it basically turned its users into the product. Advertisers could buy access to different demographics—age, gender, location, at first. But then, Facebook’s Open Graph let them track you across different apps and websites. Suddenly, everything you did online wasn’t private anymore. It was all part of this giant data machine. Drew: And who remembers those super-popular Facebook quizzes? "Which character from ‘The Office’ are you?" Harmless fun, right? Wrong! Those APIs that powered those quizzes also became sneaky spying tools for developers. Cambridge Analytica, anyone? Josh: Cambridge Analytica, yeah, that scandal was a real wake-up call for a lot of people. In 2018, the world found out that data from millions of Facebook users had been harvested without their consent and used for super-targeted political campaigns. It wasn’t just about some data breach; it was about how this data was used to manipulate people's opinions and choices, all right under Facebook's nose. Drew: Or, let’s be honest, under their watchful, but conveniently indifferent, nose, right? Facebook tried to brush it off as a small "technical oversight," but the scale of the abuse was huge, and whistleblowers had been raising alarms internally about this kind of third-party abuse for years. "Oversight," my foot! What I really want to explore here is how their whole ad system practically encouraged this kind of behavior. Josh: Exactly, you're right, it's the incentive structure. Facebook's algorithms weren’t just about showing you ads; they were about keeping you on the platform as long as possible, so they could make more money from those ads. So, I mean, the News Feed, for example, started out as just updates from your friends. But the algorithm slowly started prioritizing content that pulled in a lot of reactions. So, of course, the stuff that rose to the top was often sensational, divisive, or just plain emotionally charged. Drew: Right, it’s the algorithmic equivalent of giving kids candy instead of vegetables because, hey, candy sells better! Except here, the "candy" was misinformation, outrage, and conspiracy theories. Think about the 2016 election in the U.S., or the spread of anti-vax stuff. Facebook's system didn't care if the content was true or helpful. It just cared if people were clicking on it, sharing it, and scrolling and scrolling. Josh: And the fallout wasn’t just limited to online echo chambers or political debates. McNamee points to some of the really dark consequences, like how Facebook was tied to real-world violence. In Myanmar, for example, the platform was used to fuel ethnic hatred against the Rohingya minority. Fake news and inflammatory rumors spread everywhere, leading to mob violence and genocide. Drew: And yet, Facebook always seemed to be playing catch-up. As McNamee himself said, they’d make empty promises about "improving community standards" or "hiring more moderators," but the underlying problems with the system were never addressed. Those moderators were basically fighting an algorithm that was actively designed to spread chaos! Josh: That's really the core of the issue, isn't it? Facebook's whole model is built around engagement, and engagement often thrives on outrage or disagreement. So, even when they made changes on the surface, like briefly banning some political ads, they never actually dealt with what was causing the problem in the first place: an ecosystem designed to maximize profits no matter the social costs. Drew: And so, here we are now, dealing with the consequences of years of wild experimentation. A platform that started as a way for college students to connect has completely reshaped how we all communicate globally—for better, and, let's face it, often for worse. Josh: It's a really fundamental lesson about what happens when you innovate without thinking about ethics. We see it again and again in Facebook's story: from Facemash to Cambridge Analytica, their whole journey has been about putting profit over people. And unless they really change that, the risks we face as a society are only going to get bigger.

Societal and Democratic Ramifications

Part 3

Josh: So, understanding how Facebook grew like that really sets the stage for looking at its impact on society as a whole, right? Now we can dive into what McNamee “really” digs into in his book—how Facebook affects democracy and society. We can break it down into three levels: first, how it harms individuals, like with polarization and misinformation; second, how it's used for large-scale manipulation, like through disinformation campaigns; and third, the global fallout, you know, violence and authoritarianism. It's a logical progression that shows how design flaws in the platform can have far-reaching consequences. Drew: So, in other words, we're talking about a range of issues—from crazy conspiracy theories like Pizzagate, to election meddling, to “real” catastrophic human rights crises. I’m guessing the villains in all of these stories are the algorithms, right? Josh: Well, they’re definitely a big part of it, Drew. The News Feed algorithm, especially, turned Facebook into a place where content that got people “really” engaged, like the strongest emotional reactions–anger, fear, outrage–rose to the top. Because that kept people scrolling, and more importantly, clicking. So it created this environment where divisive and sensational stuff just thrived. Take Pizzagate, for example. Drew: Oh, yeah, the one where a guy walked into a pizza place with a rifle because he thought there was a secret child trafficking ring in the basement? Spoiler alert: there wasn’t even a basement. But let’s take a step back. How does something that sounds so ridiculous turn into “real” violence? Josh: Well, it’s like a perfect storm of how the algorithm amplifies things and how groups work together. The conspiracy theory said that political elites were running a child trafficking network out of a D.C. pizzeria. Now, that sounds totally absurd, but it got picked up in certain online communities. Facebook, designed to promote stuff that gets a lot of engagement, noticed the buzz and put those posts in the feeds of people who were already inclined to distrust authority or the media. So these echo chambers reinforced these beliefs with every share, like, or angry comment. Drew: It’s kind of fascinating—disturbing, but fascinating—how the algorithm acts like a spotlight, shining “right” on the most outrageous misinformation. You’ve got these unverified groups and moderators acting like mini free-for-alls, each one fueling the fire. And before you know it, someone feels like they have to act on what they’ve learned in these “trusted” spaces. It’s like a digital mob mentality. Josh: Exactly. And the impact on society is huge. Democracies depend on citizens who can think critically and talk about different points of view constructively. But when Facebook’s algorithms trap people in filter bubbles, that amplifies the biases they already had and encourages tribalism instead of dialogue. So it erodes trust—not just in each other, but in institutions like the press or the government. And McNamee argues that that distrust creates a breeding ground for disinformation. Drew: Okay, so about disinformation, let’s zoom out and look at Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. election. I think this is a case where Facebook goes from being just a platform to being a weapon. McNamee explains how Russian operatives used Facebook’s ad targeting tools to cause strife. Like, they promoted pro- and anti-Muslim rallies in Houston at the same time, just to make people fight. Isn’t that like trolling on steroids? Josh: It is, and it’s also incredibly strategic. The Internet Research Agency, which was the Russian group behind this, used fake accounts and paid ads to spread polarizing messages. And because Facebook lets advertisers target audiences based on demographic and behavioral data, the IRA could tailor its content to specific communities. This wasn’t just misusing the tools; it was exploiting what Facebook is all about—the same thing that sells sneakers to sports fans or diet plans to new moms. Drew: Right, but in this case, the "product" isn’t sneakers—it’s social division. McNamee doesn’t hold back on this. He says that Facebook wasn’t just caught off guard by foreign interference—it was enabled by its ad system, and then they didn’t respond until it was too late. Remember when Mark Zuckerberg said in 2016 that it was "pretty crazy" to think that misinformation on Facebook influenced the election? Well, it wasn’t crazy. Josh: Not at all. And the fallout showed how unregulated and unprepared these platforms were for political manipulation. U.S. intelligence later confirmed that these campaigns amplified tensions and, in some cases, had a measurable impact on how people voted. And the congressional hearings that followed exposed some pretty big gaps in Facebook’s accountability. McNamee’s point is clear: this wasn’t just negligence; it was a systemic failure to put the public good ahead of profits. Drew: So, we’ve got polarization, we’ve got manipulated elections. Now let’s look at it globally – in Myanmar. This, to me, seems like the darkest chapter. Facebook became the internet in Myanmar, and instead of connecting communities, it helped instigate ethnic violence. It gave a megaphone to hate speech. Josh: The Myanmar case is just tragic. The platform was the main source of information for millions of people, but it didn’t have the safeguards to moderate harmful content, especially in local languages. So that allowed military officials to spread propaganda that incited hatred against the Rohingya Muslim population. False claims, like fabricated attacks by Rohingya insurgents, spread widely, stoking fear and justifying violence. The results were just awful: mass killings, entire villages destroyed, over 700,000 Rohingya people displaced. And Facebook admitted later that it had failed to prevent misuse of the platform. Drew: "Failed"? That’s putting it lightly. It’s like pouring gasoline on a fire and then saying, "Oops, we didn’t mean for it to burn down the house." The platform focused on growth over being careful, especially in regions where the internet was new, and that left the door wide open for exploitation. Lives were lost because the leaders at Facebook didn’t want to anticipate or deal with the risks of their own technology. Josh: And McNamee makes a direct connection here: Facebook’s business model—addictive engagement, lax moderation, unchecked algorithms—just isn’t compatible with public safety. The Myanmar example isn’t just a one-time thing; it’s the extreme end of a spectrum we’ve seen over and over again. Whether it’s Pizzagate, election interference, or genocide, the structural flaws of this platform amplify harm in ways we can’t ignore. Drew: So, what’s the big takeaway here? Have we reached a point where a private tech company has outgrown its ability to be accountable? If Facebook were a country, it would be the biggest in the world—but without anything resembling decent governance. Josh: That’s “really” McNamee’s main point. Facebook’s failures aren’t just mistakes; they’re built into the way the platform works. And unless we address these systemic problems—through regulation or just completely rethinking the design—the costs to society are just going to keep getting higher.

Accountability and the Path Forward

Part 4

Josh: So, these systemic harms really force us to talk about accountability and reform – solutions that actually “do” something instead of just pointing fingers. McNamee doesn’t just say what’s wrong; he gives us a plan to tackle Facebook’s power. He's focusing on things like regulations, ethical tech, and working together, which, you know, is a huge topic. What do we do now, and how do we make sure tech helps us instead of hurts us? Drew: Accountability, huh? That's like the mythical creature everyone's hunting for but never finds. Let's start with regulations because, honestly, Facebook is like Exhibit A for why all industries—even the cool, new ones—need rules. What's McNamee suggesting here? Josh: Well, first off, McNamee says we need an "internet privacy bill of rights." Basically, users need to know exactly what's happening with their data and have control over it. The Cambridge Analytica mess showed how not being clear about things is a problem. Facebook let these third-party apps grab not just the user's data, but also their friends' – infecting millions of profiles without asking. McNamee's point is pretty simple: you should only be able to use someone's data if they agree to it, and they need to know what they're agreeing to. The law needs to back that up. Drew: Cambridge Analytica, right. The scandal that launched a thousand blog posts. But, seriously, it showed how shady Facebook's data system is. People didn't sign up to be targeted with ads based on, you know, psychographic profiles that came from their friends' silly quizzes. It's like getting a parking ticket because someone else parked your car badly. That "permission by proxy" thing was just asking for trouble. Josh: Exactly. And McNamee says those problems will keep happening if we don't make some rules. If you’ve ever tried reading a platform's terms of service, you know they’re not clear. Regulators should make the language easier to understand–no more legal jargon hiding what they're doing with your data in pages of tiny print. Also need to create easy to use systems where you can see, fix, or delete your personal data. Drew: So, basically, a "click here to get your life back" button. But I wonder – how easy will that be to enforce? Even if there are laws telling companies to do better, won't Facebook just get their lawyers involved, spend millions on lobbying, and find loopholes anyway? I mean, their legal team is probably writing these privacy violations as we speak. Josh: Good point, and McNamee talks about that too. He says regulations have to go hand-in-hand with oversight. Just passing laws isn’t enough – you need authorities with real power to enforce them. Take the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR. It’s a pretty ambitious set of rules, but even there, it’s been slow and uneven enforcing them. McNamee says we need countries to work together on data privacy, especially since platforms like Facebook operate everywhere. Drew: Speaking of operating everywhere, let’s talk about McNamee’s second big idea: ethical tech design. Because, seriously, no amount of rules will matter if the systems themselves are designed to take advantage of us. I think he calls out infinite scroll as the digital equivalent of potato chips – you don’t notice the damage until you’ve eaten the entire bag. Josh: Infinite scrolling is a perfect example of how platforms exploit our psychology. Facebook basically hacks our brains' reward systems by showing us content continuously, using something called "variable rewards." You know, it's like a slot machine – you keep scrolling, hoping to find something exciting. McNamee's argument is that this is intentional; it's designed to keep you engaged and make them more money from ads. Drew: I love this. Infinite scroll, the casino of doom! You’re not just scrolling; you’re, you know, pulling a lever, hoping for a dopamine rush. And then you end up arguing in the comments, watching workout videos you didn’t ask for, and seeing conspiracy theories you swore you wouldn’t click on. It’s digital quicksand. Josh: And it's not just about wasting time. McNamee shows how these designs that boost engagement lead to compulsive behaviors that hurt our mental health, isolate us from real life, and divide us. So, his solution? Humane technology – a design approach that cares about user well-being over endless engagement. You know, things like reminders to take breaks, screen time trackers, or content feeds that don't just keep going forever. Drew: Reminders to take breaks? That’s funny… like, "we created the problem, now we want a pat on the back for fixing it." But does McNamee really think tech companies will actually adopt humane design? Last time I checked, calm users aren’t profitable users. Josh: True, it's not in their best interest to do it themselves. That's why McNamee talks about working together. Systemic change isn't going to happen unless consumers, leaders, and tech people demand it. Look at Zuckerberg's congressional hearings, for example. Politicians grilled him about Facebook's data collection practices and how they failed to stop misinformation. Those kinds of moments matter – they get people fired up and create momentum for change. Drew: Sure, public shaming is a start. But when you're up against a giant like Facebook, working together needs to go beyond angry tweets to actual changes. Protests and hearings are loud, but how do they really change a company that seems untouchable? McNamee doesn’t actually think we can just boycott our way to fixing this, does he? Josh: Boycotts alone aren't enough, but McNamee believes in working together strategically. Users, advocacy groups, and policymakers need to join forces to demand real, structural reforms – like antitrust actions to reduce their power or groups that pressure executives. And, importantly, he says we need to embrace tech alternatives. Competition is essential to making Facebook smaller. Drew: Speaking of competition—or the lack thereof—McNamee doesn’t hold back about how monopolies like Facebook crush innovation. By acquiring Instagram and WhatsApp, they didn’t just buy out threats; they insulated themselves against progress. How does McNamee propose we tackle that kind of dominance? Break them up like old-school antitrust cases? Josh: Exactly, Drew. He draws parallels with the Microsoft antitrust case, where regulators prevented Microsoft from using its dominance to stifle competitors. McNamee suggests the same approach for Facebook: prevent further acquisitions, force a split between Instagram, Facebook, and WhatsApp, and enforce interoperability standards that allow emerging platforms to compete fairly. Drew: It’s the tech version of dismantling a LEGO Death Star. Sure, it’ll take forever, but the alternative is letting Darth Zuckerberg keep control of the internet galaxy. And honestly, imagine how different the tech landscape might be if Instagram or WhatsApp had grown independently—unhindered by Facebook’s engagement-driven culture. Josh: So, McNamee’s vision is a digital world where innovation thrives, users control their data, and platforms operate ethically. Basically, we need to reset things – a balance where technology helps humanity, not just shareholders. Drew: Bold claims, for sure. But revolutions aren't easy, and I wonder if this tech reckoning can happen fast enough to fix the damage that's already been done, you know?

Conclusion

Part 5

Josh: So, Drew, we've really been on a journey today... from Facebook's start in a Harvard dorm to its current position as a global power, constantly walking the line between innovation and, well, societal disaster. Roger McNamee's insights “really” pull back the curtain on how the platform's DNA is based on engagement at all costs. And this has created ripples of polarization, misinformation, and even violence around the world. Drew: Right, and let's not forget, all of this comes from a business model that prioritizes profit over people. From algorithms that use misinformation as a growth hack to ad systems that let the unscrupulous manipulate societies, Facebook's failures aren't just glitches... they're actually central to the design. Josh: Exactly. But McNamee doesn't just criticize. He pushes for real solutions: regulations to protect privacy, tech designs that prioritize our well-being, and collective action to reshape our interactions with technology. It’s “really” an urgent call to rethink not just Facebook, but the entire landscape of surveillance capitalism. Drew: But, the million-dollar question is: can we fix the system without completely dismantling it? And more importantly, do we have the guts to do what needs to be done? Whether it's breaking up monopolies, demanding transparency, or just deleting your Facebook account, holding these companies accountable won’t be a walk in the park. Josh: No, it definitely won't be. But the stakes are incredibly high. McNamee’s point is clear, we cannot just sit around and wait for solutions to appear. To make real changes, we'll need collective action, strong regulations, and a real commitment to ethical innovation. The future of our digital society “really” depends on it. Drew: So, the key takeaway here? Stay alert. Question the platforms that are shaping our lives, and demand systems that put people before profit. It's not just about fixing Facebook. It's about stopping this endless cycle of unchecked technological growth. Anyone up for a tech revolution? Josh: Absolutely! On that note, we leave you with McNamee's call to action: Awareness and action leads to change. Let's start holding these tech giants accountable for the world they've created – and decide together what kind of digital future we actually want.