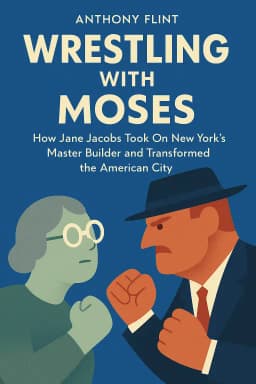

The Battle for NYC's Soul

How Jane Jacobs Took On New York's Master Builder and Transformed the American City

Golden Hook & Introduction

SECTION

Michael: Alright Kevin, I'll say a name, you give me your gut reaction. Robert Moses. Kevin: The guy who built New York. Michael: Jane Jacobs. Kevin: The woman who... stopped the guy who built New York? Michael: Exactly. And that's the wrestling match we're watching today. It’s one of the great, defining rivalries of the 20th century, and it shaped every city we live in. Kevin: I love a good David and Goliath story, and this sounds like the ultimate version. Michael: It absolutely is. We're diving into 'Wrestling with Moses: How Jane Jacobs Took On New York's Master Builder and Transformed the American City' by Anthony Flint. Kevin: And this isn't just some academic book, right? The author, Flint, has some serious credentials. Michael: He’s the perfect person to tell this story. He's not just an author; he's a long-time urban policy journalist and a fellow at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. He lives and breathes this stuff, and he brings that journalistic eye for a great story to this epic conflict. Kevin: So what was the conflict? What were they even fighting about? Michael: They were fighting over the soul of the city. It was a fundamental clash of visions for what a city should be, and it all starts with the two larger-than-life figures at the center of it all.

The Philosopher vs. The Master Builder: Two Competing Visions for the City

SECTION

Michael: On one side, you have Robert Moses. It is almost impossible to overstate the power this man had. He was never elected to a single office, yet for decades, he was the most powerful person in New York. Kevin: How is that even possible? Michael: Bureaucratic genius. He held twelve different city and state positions at the same time, wrote the laws that created his own authorities, and made himself indispensable. The result? He built modern New York. We're talking 13 bridges, 2 tunnels, 637 miles of highways, 658 playgrounds, Lincoln Center, the UN, Shea Stadium... the list is staggering. Kevin: Whoa. So he literally built the city. When you picture New York, you're picturing his work. Michael: In many ways, yes. And his philosophy was clear: progress meant building. It meant clearing out what he saw as old, "blighted" slums and replacing them with clean, orderly, large-scale projects. He saw the city as a machine that needed to be engineered for efficiency, especially for the automobile. If a neighborhood was in the way of a highway, the neighborhood had to go. Kevin: That sounds brutal. The book gives the example of the Cross Bronx Expressway, right? Where he just plowed through a thriving neighborhood. Michael: Exactly. He displaced over 1,500 families, rejecting alternative routes that would have spared them, because his route was the most direct. To Moses, people were statistics on a blueprint. The human cost was just the price of progress. Kevin: Okay, but hold on. I've seen some reviews that say this book, and the popular narrative, is a bit one-sided. Moses built parks, public pools, Jones Beach. He gave millions of people access to recreation they never had. He saw a problem—congestion, decay—and he had a solution. He was trying to fix the city, wasn't he? Michael: That's the complexity of it, and you're right to point it out. He absolutely saw himself as the hero of the story. He believed he was creating order out of chaos. But that brings us to the other side of the wrestling mat: Jane Jacobs. She looked at what Moses called "chaos" and saw something entirely different. She saw life. Kevin: So who was she? Was she a trained architect or a city planner? Michael: Not at all. And that was her superpower. She was a journalist, a mother, and an incredibly keen observer living in Greenwich Village. She had no formal credentials, which meant she wasn't indoctrinated with the conventional wisdom of the time. She just used her eyes. She would look out her window on Hudson Street and see what she called the "sidewalk ballet." Kevin: The sidewalk ballet? I love that. What does it mean? Michael: It's the intricate, unplanned dance of daily city life. The shopkeeper sweeping the sidewalk, kids playing, neighbors chatting on stoops, the mailman making his rounds. She realized that this "messiness"—this mix of homes, shops, and people of all kinds on the street at all hours—wasn't chaos. It was a complex, self-organizing system that created safety, community, and economic vitality. She called it "eyes on the street." Kevin: Right, the idea that the constant presence of people naturally polices a neighborhood. It makes it feel safe because it is safe. There's always someone watching. Michael: Precisely. And she saw that Moses's grand projects—the sterile housing towers set in empty green spaces, the highways that sliced through neighborhoods—were destroying that ballet. They were creating places that were orderly, yes, but also dead. She had this killer line in one of her articles, saying these new redeveloped downtowns would have "all the attributes of a well-kept, dignified cemetery." Kevin: Ouch. That's a powerful image. So it's basically a clash between Moses's top-down, blueprint-driven Order and Jacobs's bottom-up, organic, what-looks-like-chaos-but-is-actually-life Order. Michael: That's the perfect way to put it. And this wasn't just an academic debate. This philosophical war was fought in the streets, in the parks, and in the hearing rooms of New York City.

The Battles for New York's Soul: How a 'Bunch of Mothers' Toppled an Empire

SECTION

Kevin: Okay, so let's get to the actual wrestling. Where did they first really throw down? Michael: The first major battleground was Washington Square Park. A beloved, historic park in the heart of her own Greenwich Village. In the 1950s, Moses decided it was a traffic bottleneck and proposed to extend Fifth Avenue by running a four-lane roadway straight through the middle of it. Kevin: A highway through a park. That sounds like a caricature of a villain's plan. Michael: It does now, but at the time, it was just considered logical engineering. Moses was completely dismissive of the opposition. He famously sneered that the fight against him was being led by "nothing but a bunch of mothers." Kevin: A bunch of mothers! That's the kind of quote that comes back to bite you. How did this "bunch of mothers" even begin to fight someone that powerful? Michael: They were strategic. This wasn't just about angry protests, though there were plenty of those. A local mother named Shirley Hayes started the organizing, and Jacobs quickly became a key strategist. They did the grassroots work—petitions, flyers, traffic counts. But their real genius was in political judo. Kevin: Political judo? What do you mean? Michael: They didn't just fight Moses head-on; they used his own system against him. They realized they needed political power. So they recruited high-profile allies like Eleanor Roosevelt and Lewis Mumford. And then they made their masterstroke: they went after Carmine De Sapio. Kevin: The head of Tammany Hall? The biggest political boss in the city? Michael: The very same. He also happened to live in Greenwich Village. They pressured him, presented him with 30,000 signatures, and convinced him that protecting the Village was good politics. De Sapio went before the Board of Estimate and publicly came out against the roadway. Once the political boss turned, the other politicians fell in line. Moses was checkmated. Kevin: That is brilliant. They didn't just win an argument; they won a power struggle. Michael: And they celebrated in style. Instead of a ribbon-cutting, they held a "ribbon-tying" ceremony at the park, symbolizing that it was now permanently closed to through-traffic. The "bunch of mothers" had won. Kevin: That's an amazing story. But that was just a park. The book's climax is really about the Lower Manhattan Expressway, right? Lomex. That sounds much bigger. Michael: Infinitely bigger. This was Moses's white whale. He'd been trying to build it since the 1940s. A ten-lane, elevated superhighway that would have sliced through what we now know as SoHo, Little Italy, and the Lower East Side. Kevin: My god. The destruction would have been unbelievable. Michael: The numbers are sickening. The project would have required the eviction of 2,200 families and the demolition of over 400 buildings. It would have erased entire communities. And by the late 1960s, it looked like it was finally going to happen. The city scheduled one last public hearing, which everyone knew was a total sham. Kevin: So what did Jacobs do? Testify again? Michael: She knew testifying was pointless. She decided to invalidate the entire process. She gets to the hearing, and when it's her turn to speak, she walks up to the stage, turns the microphone to face the audience, and declares the whole thing a "phony, fink hearing." She calls the officials "insane" and warns of "anarchy" if the expressway goes through. Kevin: I'm getting chills. What happened next? Michael: She calls for a silent protest and leads about fifty people onto the stage. The chairman panics and orders her arrest. In the chaos, protesters grab the stenographer's long roll of paper—the official record of the hearing—and tear it to shreds. Jacobs grabs the mic one last time and shouts, "There is no record! There is no hearing!" Kevin: Holy cow. She literally destroyed the meeting. Michael: She did. And she was arrested and charged with inciting a riot. It was a huge risk. But it worked. The hearing was nullified, the press went wild, and the public outcry was so massive that the mayor, John Lindsay, was forced to kill the project "for all time." When a reporter asked Jacobs about her arrest, she just calmly said, "I couldn't be arrested in a better cause."

Synthesis & Takeaways

SECTION

Kevin: Wow. So she literally stopped a highway with civil disobedience. What's the lasting impact of all this? Did she actually win the war, or just these battles? Michael: She won the war. Her victory against Lomex wasn't just a local New York story; it became a national symbol. It inspired what came to be known as the "freeway revolts" in cities across America—Boston, San Francisco, New Orleans—where citizens rose up and stopped highways from destroying their neighborhoods. Kevin: And her ideas about cities, did they catch on? Michael: Completely. Her once-radical ideas are now mainstream urban planning. The concept she observed, that building more roads just creates more traffic—now known as "induced demand"—is a fundamental principle of modern transportation planning. The focus on mixed-use, walkable, human-scaled neighborhoods is the goal for almost every healthy city today. Kevin: It's interesting, though. The book's epilogue, and some critics, suggest a more nuanced view is emerging. That maybe in our rush to celebrate Jacobs, we've completely vilified Moses. And now, some cities struggle to build any big projects because of "NIMBY-ism"—Not In My Backyard. Michael: That's a crucial point. The pendulum might have swung too far. One critic made the argument that a healthy city probably needs "both perspectives." It needs the grand, visionary, get-it-done power of a Moses to build essential infrastructure like subways and bridges, but it also needs the fierce, protective, grassroots love of a Jacobs to protect its soul. Kevin: That's a great point. It's not about choosing one or the other, but finding the balance. So the wrestling match never really ends. Michael: Exactly. And that's the ultimate takeaway. Jacobs gave us the tools and the language to be part of that ongoing conversation. She taught us that the city belongs to the people who live in it, and that we have not just a right, but a responsibility to fight for it. Kevin: A powerful idea. For anyone listening who wants to get involved in their own community, or just see their city in a new light, this book is a fantastic starting point. What’s one question you think listeners should ask themselves about their own neighborhood after hearing this? Michael: Just one: Who are the 'eyes on the street' where you live? And what are they watching over? Thinking about that changes everything. Kevin: I love that. A perfect place to end. Michael: This is Aibrary, signing off.