The Revolution Began at Home

12 minGolden Hook & Introduction

SECTION

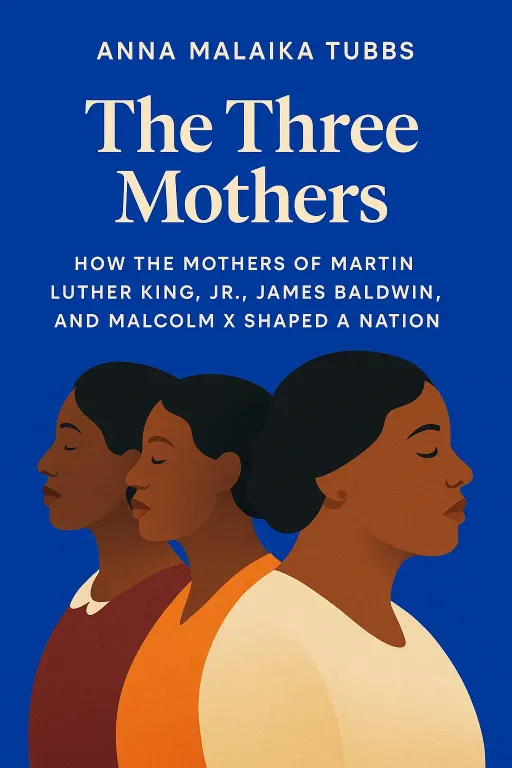

Olivia: We think we know the heroes of the Civil Rights Movement—King, Malcolm X. But the most powerful resistance wasn't a speech. It was a lullaby. It was a mother teaching her son he was worthy in a world that screamed he wasn't. That's the real origin story. Jackson: That gives me chills. It completely reframes everything. We see these men as these monumental, almost self-created figures, but you're saying the foundation was laid somewhere much quieter, much more intimate. Olivia: Exactly. And that's the revolutionary idea at the heart of 'The Three Mothers: How the Mothers of Martin Luther King, Jr., James Baldwin, and Malcolm X Shaped a Nation' by Anna Malaika Tubbs. Jackson: What's incredible is that Tubbs, a Black feminist scholar, wrote this while she was pregnant with her first child. You can feel that personal connection, that urgency to understand the legacy of Black motherhood. Olivia: Precisely. She’s not just writing history; she's living the questions. And the book itself was a massive success, nominated for major awards, because it fills such a huge, silent gap in our understanding of that era. It forces us to ask: what happens when we tell the story of a nation not through its famous men, but through the women who birthed and built them? Jackson: It feels like a necessary correction to the historical record. A story that was just waiting to be told. Olivia: This idea of motherhood as a revolutionary act is so central because it directly confronts the historical erasure of these women.

Motherhood as a Revolutionary Act

SECTION

Jackson: Erasure is a strong word. What does that actually look like? Are we talking about just being forgotten, or something more deliberate? Olivia: It’s both, and it's deeply systemic. The book opens by establishing the brutal context for Black motherhood in America. It's not just about being overlooked in history books; it's about a history where Black women's bodies were treated as objects, not as human. Jackson: Okay, so this goes way beyond just a lack of recognition. Olivia: Far beyond. Tubbs brings up the horrifying history of American gynecology. The so-called "father" of the field, J. Marion Sims, perfected his techniques in the 19th century by performing experimental surgeries on enslaved Black women. Without anesthesia. While they were held down. Jackson: Wait, what? That's monstrous. So the very foundation of modern medicine for women was built on this horror? How does a mother even begin to trust a system like that? Olivia: That’s the core of the terror. And it didn't just end with slavery. Tubbs connects this historical trauma to the present-day crisis in Black maternal health. She shares her own story of finding out she was pregnant on Valentine's Day in 2019. She felt this incredible joy, but it was immediately mixed with fear. Jackson: Because she knew the statistics. Olivia: She knew the statistics. Black women in America are still three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women. And that disparity cuts across education and income levels. It's not about wealth; it's about a system that has historically devalued and disbelieved Black women. Jackson: Wow. So for Alberta King, Louise Little, and Berdis Baldwin, just the act of deciding to have a child, to bring a Black baby into this world, was an act of profound defiance. It was a vote for a future that the world around them was actively trying to extinguish. Olivia: It was a revolutionary act of hope. They were choosing to create life in the face of a society that was, in many ways, obsessed with Black death and control. The book quotes Audre Lorde, saying, "the fabric of our lives is stitched with violence and with hatred, that there is no rest." These mothers knew that intimately. Jackson: And they had to prepare their sons for that reality. It wasn't just about teaching them to read and write; it was about teaching them how to survive. Olivia: And not just survive, but to believe in their own worth. To see themselves as whole and human when every message from the outside world told them they were not. The book argues that this work—this constant, vigilant, emotional labor—is a form of activism that has been completely ignored. Jackson: It’s invisible work. But it’s the work that made everything else possible. You can't lead a march for justice if you don't first believe you are worthy of it. Olivia: And that belief was forged in their homes, by their mothers. It was their first and most important education. The book makes it clear that without this foundational work, the Civil Rights Movement as we know it simply wouldn't exist. Jackson: That’s a massive claim, but it feels undeniably true. It shifts the center of gravity of the entire historical narrative. Olivia: Exactly. And that's what makes their individual stories so powerful. They didn't just survive; they created three completely different blueprints for how to raise a Black son to challenge the world. They weren't a monolith.

Three Blueprints for Survival

SECTION

Jackson: Okay, I love that idea of "three blueprints." It suggests there's no single right way to resist. What did those different approaches look like? Olivia: They were incredibly distinct, shaped by their origins and personalities. Let's start with Louise Little, Malcolm X's mother. She was from Grenada, raised on stories of anti-colonial rebellion. Her family was deeply involved in Marcus Garvey's movement, the UNIA. Jackson: Right, the Universal Negro Improvement Association. That was all about Black pride, economic independence, and a connection back to Africa, right? Olivia: Precisely. It was a global movement of Black self-reliance. And Louise embodied that spirit. The book tells this absolutely harrowing story. She's in Omaha, pregnant with Malcolm, and her husband Earl is away organizing for the UNIA. One night, the Ku Klux Klan rides up to their house on horseback, carrying rifles, shouting threats. Jackson: Oh my god. Alone? Olivia: Alone with her three small children. And what does she do? She doesn't hide. She opens the door, stands on the porch, and confronts them. She tells them Earl isn't home, that she's there alone with her children, and she does it with such calm authority that they are momentarily stunned. They end up smashing the windows and riding off, but she never cowered. Jackson: Wow. That's not just courage; that's a political statement. She's refusing to be intimidated, refusing to accept their power over her. Olivia: It's pure Garveyism in action. She taught her children, especially Malcolm, that their minds were their own, that they should question everything, and that they should never, ever believe they were inferior. That fire in Malcolm X? That unwavering belief in Black autonomy? It came directly from Louise. Jackson: Okay, so that's one blueprint: fierce, political, intellectual resistance. What about Alberta King, Martin Luther King Jr.'s mother? Her story feels different. Olivia: Completely different, but no less powerful. Alberta grew up in Atlanta, in the heart of the Black church. Her father, Reverend A.D. Williams, was a titan. He wasn't just a preacher; he was a community builder. After the horrific Atlanta Race Riot of 1906, he helped lead the Black community's response. He was a founder of the local NAACP chapter and led the fight to get the city to build the first public high school for Black students. Jackson: So her activism was rooted in community and faith. It was about building institutions. Olivia: Exactly. It was generational. Alberta inherited this legacy of what the book calls "social gospel Christianity"—the belief that faith demands action for social justice. She was a highly educated woman, a talented musician who directed the church choir for decades. Her resistance wasn't about fiery confrontation in the same way as Louise's; it was about building a world of dignity and excellence within the Black community. Jackson: And that’s the world she raised Martin in. Olivia: Yes. The book tells the famous story of a young Martin being told he could no longer play with his white friends because they were now going to segregated schools. He was devastated. His father gave him a lecture on the evils of segregation, but it was Alberta who sat with him and gave him the lesson that would define his life. She told him, "You are as good as anyone." Jackson: Simple words, but everything is in them. Olivia: Everything. She instilled in him an unshakable sense of his own God-given worth. That belief, that deep spiritual certainty in human dignity, became the bedrock of his nonviolent philosophy. Her blueprint was faith, education, and the power of a beloved community. Jackson: Wow, so you have Louise with this fierce, political fire, and Alberta with this deep community and faith-based power. Then there's Berdis Baldwin, James Baldwin's mother. Her story seems the quietest of the three. Olivia: It is, and in some ways, the most heartbreakingly personal. Berdis grew up on the isolated Deal Island in Maryland and later moved to Harlem. She married a preacher, David Baldwin, who was James's stepfather. David was a man broken by the relentless racism of America. He was bitter, paranoid, and often cruel, especially to James, who he saw as "ugly" and different. Jackson: That sounds incredibly painful. How do you resist something that's inside your own home? Olivia: Berdis's resistance was an act of profound emotional and spiritual protection. While her husband was tearing James down, Berdis was tirelessly building him back up. She was the one who saw his brilliant mind, his sensitive soul. The book describes how she would intervene, shielding James from his stepfather's rage. When a white teacher saw James's talent and wanted to take him to plays, his stepfather forbade it. Berdis defied him and let James go. Jackson: She was saving his spirit. Olivia: She was saving his life. His artistic life, his emotional life. Her blueprint was about creating a space for love and humanity to survive in the most toxic of environments. She taught him that love was more powerful than hate, not as a political slogan, but as a daily practice of survival. Jackson: And that's the core of James Baldwin's work, isn't it? That unflinching look at the pain of racism, but always, always, with this undercurrent of love and the need for human connection. Olivia: It's all there. His ability to bear witness to America's soul came from the soul his mother so carefully protected. Three mothers, three different worlds, three unique forms of armor they crafted for their sons.

Synthesis & Takeaways

SECTION

Jackson: It's incredible. We see these men as titans, but this book reframes them as legacies. They were the sparks, but their mothers were the embers, as the book says. Olivia: Precisely. And the book's ultimate argument is that this isn't just history. The same forces that tried to erase these women—the misrecognition, the systemic neglect—are still at play. The author, Tubbs, makes it clear that this is an ongoing struggle. Jackson: You mentioned the maternal mortality rates earlier. It’s a direct through-line. Olivia: A direct, and deadly, through-line. When Black women are three to four times more likely to die in childbirth than white women, that's not a historical footnote; it's a present-day crisis rooted in the same dehumanization that Louise, Alberta, and Berdis fought against. Jackson: So the book is more than a biography; it's a call to action. It’s asking us to see the invisible labor, the uncelebrated resistance, that is still happening all around us. Olivia: It is. It’s asking us to recognize that the fight for justice doesn't always look like a march or a boycott. Sometimes it looks like a mother reading to her child. Sometimes it's defending a child's dream. Sometimes it's just holding on to love in a world full of hate. Jackson: That makes me think... the real takeaway is to look for that uncelebrated labor, the quiet resistance, in the people around us. Who are the 'three mothers' in our own lives whose stories we've overlooked? Olivia: That's a powerful question for all of us. And it's a beautiful way to honor the legacy of these three incredible women. We'd love to hear your thoughts. Join the conversation and let us know what this book brings up for you. Jackson: It’s a book that will definitely stay with you long after you finish it. A truly essential read. Olivia: This is Aibrary, signing off.