The Poetry and Music of Science

9 minComparing Creativity in Science and Art

Introduction

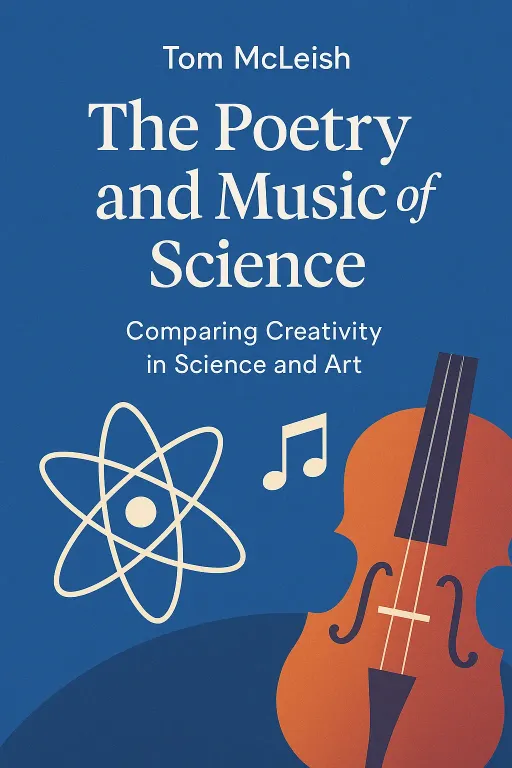

Narrator: A scientist and a professor of fine art walk into a room. It sounds like the beginning of a joke, but for physicist Tom McLeish, it was the start of a revelation. The artist, Ken Hay, began describing his creative process: the initial concept, the frustrating struggle of confronting his ideas with the physical constraints of paint and photographic print, and the cycle of reformulation and repeated attempts. As McLeish listened, he was struck by a profound sense of familiarity. He realized he could describe his own scientific research in almost precisely the same terms—the same emotional trajectory of excitement, hope, disappointment, and eventual resolution. This conversation crystallized the central question of his work: what if the perceived chasm between the arts and sciences is an illusion? In his book, The Poetry and Music of Science, Tom McLeish dismantles this long-held cultural divide, revealing the shared, deeply human creative processes that lie at the heart of both disciplines.

The Myth of Two Cultures

Key Insight 1

Narrator: The book argues that the conventional separation of human endeavor into two distinct cultures—the logical, rigid world of science and the imaginative, free-flowing world of the arts—is a damaging oversimplification. This divide obscures the fundamental truth that both fields are born from the same creative impulse: the desire to impose a cosmos upon chaos. McLeish points out that this perception is deeply ingrained. The poet William Wordsworth, for instance, contrasted the scientist's work as a "personal and individual acquisition," slow to come and lacking sympathy, with the poet's song, in which all of humanity joins.

This view portrays science as remote and inaccessible, lacking the "ladder of access" that allows the public to engage with art on multiple levels, from casual appreciation to deep study. However, McLeish contends that this is a failure of communication, not a fundamental difference in nature. Both a scientist developing a theory and an artist composing a symphony are engaged in a delicate dance between imagination and constraint. A scientist’s imagination is constrained by physical laws and experimental data, just as a sculptor’s is by the properties of stone. The goal of the book is to rebuild the bridge between these two worlds by showing that their intellectual and emotional histories are not just parallel, but deeply intertwined.

Science's Hidden Engine of Imagination

Key Insight 2

Narrator: While the "scientific method" is often taught as a linear process of hypothesis, experiment, and conclusion, McLeish argues this framework only describes how ideas are tested, not how they are born. The true genesis of a scientific breakthrough lies in a creative, imaginative leap that the formal method cannot account for. As Albert Einstein noted, "The mere formulation of a problem is far more essential than its solution." This act of formulating the right question requires a powerful imagination.

The story of physicist Richard Feynman’s discovery of the V-A coupling in beta decay serves as a powerful illustration. In the 1950s, particle physics was a confusing mess of experimental data. Feynman, driven by intuition, began exploring a new theory about the interaction between particles. He described the process not as a cold, logical deduction, but as a thrilling, personal quest. When his calculations finally aligned with the data, revealing a new law of nature, his overwhelming feeling was one of privilege and awe. He later recalled the moment with a sense of wonder, stating, "I knew a law of nature that nobody else knew." This experience—the emotional, aesthetic reward of discovery—is a core part of the scientific process, yet it is rarely part of its public narrative.

Seeing the Unseen Through Metaphor

Key Insight 3

Narrator: A crucial tool shared by both artists and scientists is the power of visual imagination and metaphor to make the abstract concrete. This is especially true in fields that deal with phenomena far beyond our everyday experience. In polymer physics, for example, scientists struggled to understand why "star polymers"—molecules with multiple arms radiating from a central point—flow so much more slowly than their linear-chain counterparts. The pure mathematics of the problem was intractable.

The breakthrough came not from an equation, but from a picture. Scientists imagined the long, linear polymers moving like a snake slithering through a narrow pipe, a process they called "reptation." Star polymers, however, couldn't do this. Their branched structure meant they were hopelessly entangled. The clarifying analogy became that of an "octopus in a fishing net." To move, the octopus can't just slide forward; it must painstakingly withdraw its arms one by one and shuffle through the mesh. This visual metaphor captured the essential physics of the star polymer's movement, allowing scientists to build a new, more accurate mathematical model. This process—passing from an intuitive visual idea to a formal mathematical description—demonstrates that science often relies on imaginative, picture-based thinking to navigate complexity.

The Emotional Core of Creation

Key Insight 4

Narrator: Challenging the stereotype of the detached, dispassionate researcher, McLeish asserts that emotion is not a contaminant in science but an essential fuel for creativity. Desire, longing, frustration, and joy are not just byproducts of the work; they are often the driving forces behind it. While scientists may be reluctant to discuss this in formal publications, their personal accounts are filled with emotional language. Einstein himself described his decade-long search for general relativity as years of "anxious searching in the dark, with their intense longing."

A modern, powerful example is the work of Caltech chemical engineer Julie Kornfield and her team to develop a fire-safer jet fuel. The project was directly inspired by the horrific fires in the 9/11 attacks. Driven by a powerful desire to prevent future tragedies, the team worked for years to create a fuel that wouldn't explode on impact. The project was fraught with technical setbacks, but their emotional commitment and a clear vision of their goal acted as a "guiding beacon." When they finally succeeded, the achievement was not just an intellectual victory but a deeply emotional one. This story reveals that science, at its best, is a profoundly human activity, motivated by our deepest values and a desire to make a difference in the world.

A Shared Conversation Across Centuries

Key Insight 5

Narrator: The relationship between science and the arts is not a new idea but a long, continuous conversation that has shaped both fields. McLeish highlights the work of Alexander von Humboldt, the 19th-century Prussian explorer and natural philosopher, as a prime example of this synthesis. Humboldt's expeditions in South America were characterized by meticulous data collection, but his goal was grander than mere cataloging. He sought to understand nature as a single, interconnected system—a "cosmos."

Crucially, Humboldt communicated his findings not in dry, academic prose, but in vivid, compelling writing that blended scientific observation with literary artistry. He saw no contradiction between measuring atmospheric pressure and describing the sublime beauty of a mountain range. His work inspired not only scientists like Charles Darwin but also writers and poets like Emerson and Thoreau. Humboldt’s legacy is a powerful reminder that a holistic understanding of the world requires both the analytical precision of science and the evocative, meaning-making power of the arts. They are two essential languages for telling the story of the universe and our place within it.

Conclusion

Narrator: The single most important takeaway from The Poetry and Music of Science is that creativity is not the exclusive domain of the arts, nor is logic the sole property of science. Both are fundamental human endeavors that spring from the same source: a deep-seated need to find order, meaning, and beauty in the universe. They are two sides of the same coin, two modes of a single, imaginative inquiry into the nature of reality.

By tearing down the artificial wall between the "two cultures," Tom McLeish challenges us to see the world with new eyes. He invites us to recognize the poetry in a well-crafted equation and the rigorous structure in a masterful painting. The ultimate challenge the book leaves us with is to foster this integrated vision in our education and our culture, and to finally appreciate that the impassioned, creative search for truth—whether in a laboratory or a studio—is one of humanity's most noble and unifying pursuits.