The Picture of Dorian Gray

9 minIntroduction

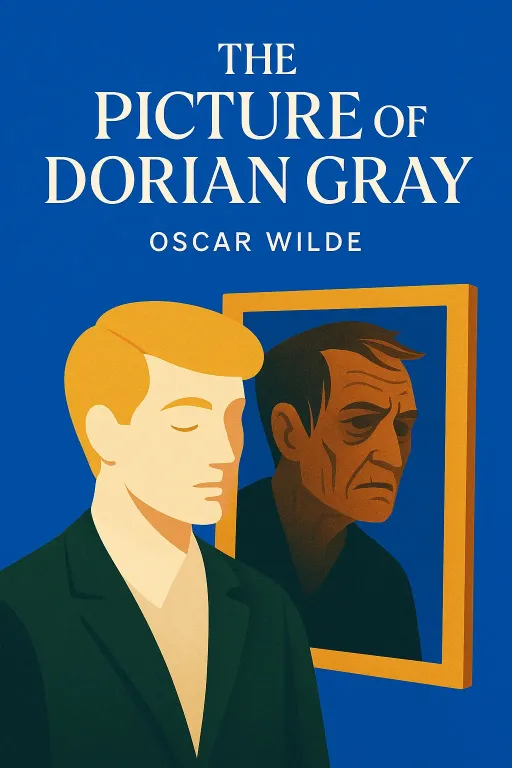

Narrator: What if you could remain forever young, forever beautiful, while a hidden portrait bore the weight of your age and every sin you committed? What if your face remained a mask of innocence, no matter the darkness that festered in your soul? This is not just a fantasy, but the central, terrifying premise of a story that explores the high price of eternal youth and the corrupting power of unchecked influence. In his masterpiece, The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oscar Wilde crafts a haunting gothic tale that examines the dangerous relationship between beauty, morality, and the self. It follows a young man who makes a Faustian bargain, trading his soul for a life of endless pleasure, only to discover that every choice leaves an indelible mark.

The Faustian Bargain

Key Insight 1

Narrator: The story begins in the London studio of the artist Basil Hallward, a man consumed by his latest subject: the exquisitely beautiful Dorian Gray. Basil confesses to his friend, the witty and cynical Lord Henry Wotton, that the portrait of Dorian is his finest work, but one he can never exhibit. He believes that "every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter," and fears he has revealed too much of his own idolatrous adoration for the young man.

Intrigued, Lord Henry insists on meeting Dorian. When he does, he immediately begins to poison Dorian’s innocent mind with his hedonistic philosophy. He speaks of the transience of beauty and the tragedy of youth, urging Dorian to live life to its fullest and yield to every temptation. "The aim of life is self-development," Lord Henry declares. "The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it."

Upon seeing the finished portrait, Dorian is struck for the first time by his own stunning beauty and the horrifying realization that it will one day fade. While the painting remains perfect, he will grow old and wrinkled. In a moment of passionate despair, he makes a fateful wish: "If it was only the other way! If it was I who were to be always young, and the picture that were to grow old! For this… I would give my soul!" Unbeknownst to him, his wish is granted, setting the stage for his moral decay.

The First Test of the Soul

Key Insight 2

Narrator: Dorian, now under Lord Henry’s spell, begins his pursuit of new sensations. He wanders into a shabby theatre and falls madly in love with a young actress, Sibyl Vane. To Dorian, Sibyl is not a person but an artistic vessel; he loves her because she is Juliet one night and Rosalind the next. He becomes engaged to her and, in his excitement, invites Basil and Lord Henry to witness her genius.

However, the night they attend, Sibyl’s performance is a disaster. It is flat, artificial, and devoid of passion. After the play, Dorian confronts her backstage. Sibyl explains, with joy, that she can no longer act because her love for him has shown her the difference between the stage's hollow shadows and real life. Before meeting him, art was her reality; now, he is.

Dorian is disgusted. His love was for her art, not for her. "You have killed my love," he tells her coldly, leaving her sobbing on the floor. When he returns home, he notices a subtle but undeniable change in his portrait: a new touch of cruelty has appeared around its mouth. Horrified, he realizes his wish has come true. The portrait is now the mirror to his soul, and it will bear the burden of his sins. He briefly resolves to make amends with Sibyl, but it is too late. The next day, Lord Henry arrives with the news that Sibyl Vane has committed suicide. Instead of feeling guilt, Dorian, guided by Lord Henry’s aesthetic framing of the tragedy, chooses to see her death as a beautiful, dramatic end to a perfect romance, marking his first step away from remorse and toward cold detachment.

The Descent into Hedonism

Key Insight 3

Narrator: Following Sibyl’s death, Dorian fully embraces a life of pleasure and sin, using the "poisonous" yellow book sent by Lord Henry as his guide. The book, a study of a young Parisian who indulges in every passion, becomes Dorian’s blueprint for a new hedonism. He locks the portrait away in a disused schoolroom at the top of his house, visiting it periodically to watch its grotesque transformation. While his own face remains untouched by time or corruption, the figure on the canvas grows more hideous with every transgression, its features twisted by sin and age.

For years, Dorian leads a double life. In high society, he is a charming and admired figure, a patron of the arts known for his exquisite taste and unchanging youth. But in the shadows, he descends into London's sordid underbelly, frequenting opium dens and engaging in unspeakable vices. Rumors begin to swirl around him. Young men in his circle find their reputations ruined, their lives destroyed. Yet, society cannot reconcile these dark tales with Dorian’s pure and innocent face. His beauty becomes his shield, allowing him to escape the consequences that would befall any other man.

The Point of No Return

Key Insight 4

Narrator: Years later, on the eve of his thirty-eighth birthday, Dorian encounters Basil Hallward, who is about to leave for Paris. Basil confronts Dorian about the terrible rumors that follow him, pleading with him to use his influence for good. He laments that he can no longer recognize the innocent boy he once painted. In response, Dorian, with a cruel smile, offers to show Basil his soul.

He leads the horrified artist to the locked room and unveils the portrait. Basil stares in disbelief at the monstrous, leering face on the canvas, a hideous mockery of the masterpiece he created. He recognizes his own brushwork but sees the eyes of a devil. He begs Dorian to pray for repentance. But at that moment, an uncontrollable hatred for Basil—the man who created the painting that has become his conscience—seizes Dorian. He grabs the knife he used to kill Basil and stabs him repeatedly, murdering his old friend.

The murder marks Dorian’s complete descent into depravity. Now a cold, calculating criminal, he blackmails a former friend, the scientist Alan Campbell, into using his chemical knowledge to dispose of Basil’s body, leaving no trace of the crime. By forcing Campbell’s hand, Dorian destroys another life; Campbell later commits suicide, unable to live with what he has done.

The Inescapable Consequence

Key Insight 5

Narrator: Despite his crimes, Dorian attempts to find redemption. He tells Lord Henry he has performed a "good deed" by sparing a village girl, Hetty Merton, whom he had been courting. He believes this act of renunciation should have begun to reverse the portrait's corruption. But when he checks the painting, he is horrified to find it has only grown more loathsome, with a new look of cunning hypocrisy marring its features. He realizes his "good deed" was not born of selflessness but of vanity and a desire for new sensations.

He understands then that there is no escape. The portrait is not just a record of his actions but of his intentions. It is the living death of his soul. Believing that destroying the painting will kill his past and set him free, he seizes the same knife he used to murder Basil and plunges it into the portrait.

A terrible cry echoes through the house. When his servants finally break down the door to the schoolroom, they find a magnificent portrait of their master as a beautiful young man hanging on the wall. Lying on the floor is the body of a withered, wrinkled, and loathsome old man, with a knife in his heart. It is only by the rings on his fingers that they recognize him as Dorian Gray.

Conclusion

Narrator: The ultimate takeaway from The Picture of Dorian Gray is the profound and inescapable link between the soul, the body, and one's actions. Wilde demonstrates that beauty, when severed from morality, becomes a monstrous force. Dorian's attempt to separate his physical self from his spiritual self—to live a life of sin without consequence—is doomed to fail. The portrait serves as a powerful symbol that while one can hide their sins from the world, they can never hide from themselves.

The novel leaves us with a chilling question about the nature of influence and the true cost of our desires. Dorian was a product of his own vanity, but he was also shaped by Lord Henry's seductive words and Basil's worshipful art. It challenges us to consider: how much of our identity is our own, and how much is a reflection of the world's gaze? And if given the chance for eternal beauty, what price would we be willing to pay?