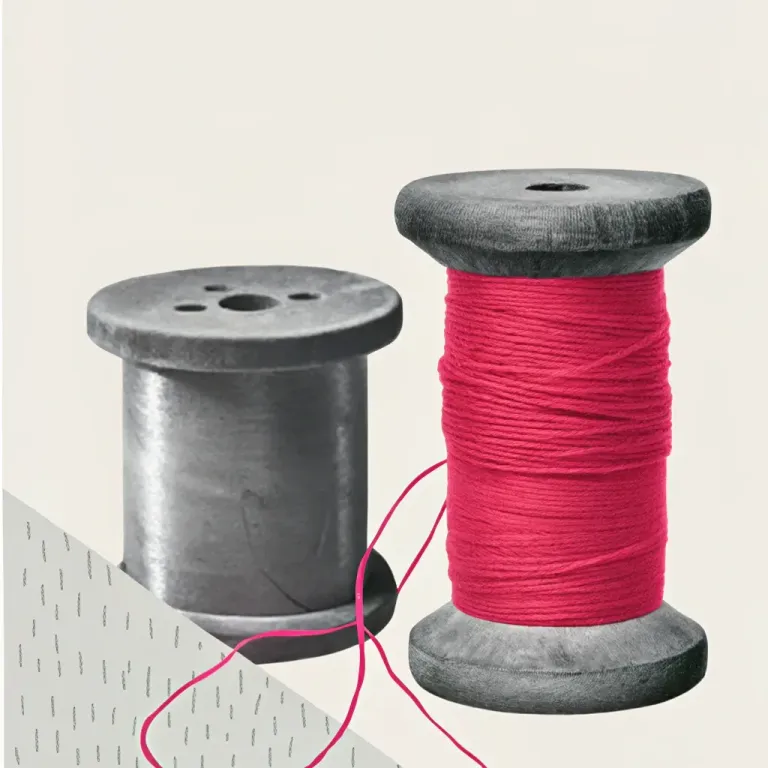

Connect the Dots: Innovation's Hidden Threads

Podcast by Chasing Sparks with Alex and Justine

Weaving Together Connections for Brilliant Ideas and Profitable Innovation

Connect the Dots: Innovation's Hidden Threads

Part 1

Alex: Hey everyone, and welcome! Today, we're diving into the exciting world of innovation and how those unexpected connections can spark really groundbreaking ideas. Justine: <Sarcastically> Oh great, another episode where we discover the secret to unlocking human potential is, like, positive thinking and a vision board? Alex: <Laughing> Almost, Justine, but not quite! We're actually talking about Red Thread Thinking by Debra Kaye. The core concept is that innovation isn't some magical thing, but really the result of spotting and connecting hidden threads that are already there. Justine: So, it's like a super-charged "aha!" moment treasure hunt, got it. But seriously, how is this different from, you know, all the other innovation advice out there? Alex: Kaye doesn’t just throw theories at you; she backs everything up with compelling case studies, solid scientific insights, and practical strategies you can actually use. It’s not just about making new stuff – it’s about making things that truly matter. And she puts a huge emphasis on weaving in empathy, resilience, and, most importantly, ethics. Justine: Ethics? So, no ruthless business tactics or tech bros trying to take over the world? Alex: Exactly. She looks at how really understanding people, the surrounding culture, and even learning from past “failures” can lead to surprisingly impactful, responsible solutions. Justine: Okay, you've piqued my interest. So, what's on the agenda for today? Alex: We're breaking down innovation into three key threads. First, we'll nail down the crucial difference between just being creative and actually innovating—that is, turning cool ideas into real action. Then, we'll explore how looking at the past with a little serendipity can inspire fresh solutions. And finally, we're diving deep into how understanding human behavior and culture is vital for creating innovations that truly connect with people. Justine: Got it. Creativity versus actually doing something, mining the past for inspiration, and then figuring out what makes people tick. Sounds like a pretty comprehensive look at the science and the soul of innovation. Alex: Precisely. So, let's get ready, because this isn't just about grand visions—it’s about weaving together ideas that actually work in the real world. Let's jump in!

The Foundations of Innovation

Part 2

Alex: So Justine, we've got our agenda laid out, but let’s kick off with this crucial distinction between creativity and innovation. People often treat them as synonyms, but the book “really” sets them apart, doesn't it? Justine: Exactly. People often just throw those two words around like they mean the same thing. But the book sees them as different, right? Alex: Totally. Creativity is this expansive, free-flowing process – like a playground for ideas, where anything goes. You can dream up a flying car, no strings attached! Innovation, though, is about taking that initial spark and figuring out the practicalities – making it functional, marketable, and impactful. It's the hard, disciplined work of turning those wild ideas into reality, making them actually "take off," both literally and figuratively. Justine: So, creativity is like a kid doodling with crayons, and innovation is an engineer trying to figure out how to actually make those doodles fly with a jet engine attached? Alex: That's... one way to put it. A more down-to-earth example could be the smartphone. The creative idea was adding a camera or music player to a phone. But the innovation was seamlessly integrating all of that into one device. Just having the idea wasn't enough; you needed the design, the tech, the user experience to make it all work and sell. Justine: Right, because it’s not “really” “innovative” if it just gathers dust in a lab somewhere, right? It needs to get into people's hands. Speaking of phones, what helps people go from that initial doodle to the engineering phase? It can't just be leaving it to the geniuses in isolation, can it? Alex: Definitely not. Kaye actually points out a few key ways to build that "bridge," both in ourselves and in teams. Number one is cognitive flexibility. It’s basically seeing the connections – spotting patterns between things that seem totally unrelated. And just like a muscle, you can actually train it, especially through metaphorical thinking – finding parallels between seemingly different areas. Justine: Metaphorical thinking? That sounds more like something you'd do at a poetry slam than in a serious product development meeting. How does that even work? Alex: Well, imagine you're dealing with a supply chain problem. If you think of it as navigating a maze, all of a sudden you start seeing alternate routes, or strategies you might have missed before. By reframing a situation metaphorically, you unlock creative solutions from angles that weren't obvious at first glance. Justine: Okay, I get it. It's like turning a complicated spreadsheet into a game of Tetris – less intimidating, more manageable. Alex: Precisely! Another good way to build cognitive flexibility is journaling. Writing down your thoughts, spotting patterns, or just untangling the mess in your head, it often leads to unexpected insights. And journaling isn't just for writers or dreamers – it's a structured way to process thoughts and turn chaos into actionable steps. Justine: So journaling is less about "Dear Diary" and more about "Dear Journal, I think I've cracked the code for a portable MP3 player... maybe I'll call it an iPod." Alex: Well, the idea itself sounds still like creativity, but it could turn into innovation if you kept at it! Another key thing Kaye mentions is creating unstructured mental space. Relaxation actually helps, it promotes what researchers call the "incubation effect." You know how you get stuck on a problem, and then bam! – the solution hits you in the shower? Your subconscious keeps working even when you consciously step away. Justine: Ah, the classic Archimedes-in-the-bathtub moment, right? Let me guess, it's easier to be inspired when you're not chained to your inbox. Alex: Exactly! I mean, Archimedes had his "Eureka!" moment after observing water displacement while bathing, and Tim Berners-Lee conceived the World Wide Web while envisioning the interconnectedness of ideas in a relaxed setting – not a lab. These moments aren’t accidents; they're the result of relaxation allowing your brain to connect the dots. Justine: But seriously, who has time for long bubble baths and meditative walks? Also, how do the places we spend most of our time impact the way we think? Alex: Oh, the environment is crucial. It's about designing spaces – physically, emotionally, and collaboratively – that encourage exploration and tolerate failure. It's not just a feel-good idea to foster resilience and optimism in teams. It creates a safe space to experiment, challenge norms, and bounce back from setbacks. Without it, you stagnate. Justine: So an office beer fridge and some beanbag chairs aren't enough, then? Alex: Exactly. You need a culture of support where mistakes aren't punished, but are seen as learning opportunities. Companies like 3M are great at this with their flexible work policies and how they embrace serendipity. The Post-it Note, for example. Spencer Silver’s low-tack adhesive was initially seen as a "failure" because it wasn't meant to make sticky notes. But instead of binning the idea, 3M let employees like Art Fry find new uses for it – and now it's one of their most well-known products! Justine: So failure isn't the end of the line, it's just another part of the process. That’s a pretty optimistic way to look at setbacks. Alex: And that optimism fuels innovation! Leaders who see challenges as opportunities rather than obstacles can “really” unlock potential. That proactive attitude, together with collaborative and supportive environments, sets the stage for ideas to thrive. Justine: Makes you wonder how many “failed” ideas are just waiting for someone to give them another look. It's like a thrift store for concepts – dust off something that looks useless, and suddenly it's a bestseller.

Learning from the Past and Serendipity

Part 3

Alex: Now that we've laid the groundwork for understanding innovation, let's explore how past experiences and those unexpected, serendipitous discoveries can actually fuel new ideas. This is where we really get into what Kaye talks about: the power of learning from the past and embracing the unexpected. It’s not just about charging ahead but also looking back, you know, re-evaluating, and recombining things that already exist. Justine: So, it’s like giving old ideas a second shot at the big time? Dusting off forgotten things and turning them into something valuable. Alex: Exactly! This bridges historical insights with human-centered innovation, highlighting the value of old knowledge and those chance encounters in the creative process. One incredible example is the story of Thalidomide. Justine: Thalidomide! Oh, that rings a bell – wasn't that the drug from the 50s? The one given to pregnant women for morning sickness that caused terrible birth defects? So, where's the innovation here? Sounds more like a cautionary tale, right? Alex: It started as a tragic failure, absolutely. But that's why its eventual redemption is so remarkable. Decades after it was pulled off the market, researchers took another look and discovered a completely new use for it. It turned out the drug could inhibit angiogenesis, which is the formation of blood vessels. This made it a powerful tool in treating certain cancers and leprosy. By cutting off a tumor's blood supply, it became a life-saving cancer treatment. Justine: Wow, from a cautionary tale to a cancer-fighting agent. Talk about a comeback story! Alex: Exactly! It’s a case study in why it’s so important to have an open mind when re-examining old technologies. Instead of completely writing it off, scientists were willing to explore Thalidomide's properties in a new light, under new conditions. And that’s the kind of mindset innovators need—acknowledging past failures while still being open to future potential. Justine: It's like, looking at your worst screw-up and thinking, ‘Hey, maybe there's something useful here after all.’ Does that mean we should hoard every rejected idea until its redemption arc? Alex: Well, not every single one, of course. But you’d be surprised how often the context changes and suddenly makes something dismissed earlier valuable. Sometimes, successful innovation just means being willing to revisit what didn't work before and reinterpret it with new tools, new knowledge, or even a different cultural perspective. Justine: Okay, so Thalidomide shows us the value of looking back. But how does serendipity fit in? That seems less about planning and more about just dumb luck, right? Alex: Exactly! Although serendipity in innovation isn’t completely random. It’s about being observant enough to notice potential in unexpected moments. Think about Bette Nesmith Graham and Liquid Paper. She was a secretary constantly dealing with typing errors and, you know, had a moment of inspiration thinking like a painter. She created quick-drying white paint to cover mistakes. What started as a personal fix turned into Liquid Paper, which revolutionized office work. Justine: So, instead of just getting mad about typos, she bottled a solution, literally!. That’s a clever way to turn annoyance into an opportunity. No huge lab or team needed, it was just one person solving her own problem. Alex: Exactly! And that's the beauty of user-driven ingenuity. Another example is Spencer Silver at 3M, who accidentally created a weak adhesive. At first, it seemed useless—it wouldn’t stick permanently. But then his colleague, Art Fry, repurposed it for temporary bookmarks, and bam, Post-it Notes! Justine: So, something that seemed like a total failure became a multi-million-dollar innovation. Alex: Right! These stories highlight that failure isn’t the end. It’s frequently a detour leading to something entirely unexpected but valuable. They also show the importance of curiosity and building environments where these kinds of “accidents” are encouraged to evolve into ideas. Justine: Okay, but not everyone's stumbling upon life-changing adhesives or painting their way out of struggles. Can you actually strategize for pure luck? Can you intentionally set yourself up to have these kinds of breakthroughs? Alex: Absolutely! That’s where tools like "serendipity generators" come into play. Kaye suggests designing environments that bring different perspectives together, like cross-disciplinary brainstorming sessions. Mixing teams from engineering, marketing, and design gives you different viewpoints, and those collisions can spark fresh ideas. Justine: Intellectual speed-dating – stick an aerospace engineer in a room with a graphic designer, and something’s bound to happen, right? Alex: Exactly! Another approach is conducting thorough audits of past technologies. You revisit old products, ideas, or projects that were shelved, looking for overlooked potential. Sometimes a concept was ahead of its time or lacked the right market conditions. Reassessing these ideas in today’s context can uncover opportunities you wouldn’t have seen before. Justine: Basically, rummaging through the company attic for buried treasure. Alex: Exactly! And then there’s also immersive observation. Innovators immerse themselves in their users’ lives, noticing how they adapt or "hack" products for unintended uses. These workarounds can give huge hints for innovation. Justine: So, watching people misuse your product could actually spark your next successful redesign? That's strangely inspiring. Alex: It’s true across industries. A classic example is how snack companies realized they could sell smaller, single-serving bags because people were already portioning larger bags into Ziploc containers. It’s all about paying attention to where innovation is happening already, often right under your nose. Justine: Alright, I see the value in creating environments and ways to catch lightning in a bottle. But is there an overarching strategy tying this together? Something that connects serendipity, revisiting the past, and everything in between? Alex: Yes! It’s the idea of recombination. Innovation thrives when you take pieces from different sources – sometimes old, sometimes unexpected – and merge them into something new. Think of Rubik and his cube. He combined design, mathematics, and play to create a timeless puzzle. Or Apple—they didn’t invent the individual parts for a smartphone, but they recombined them into a groundbreaking whole. Justine: Ah, the good old "mashup" principle of innovation. Makes sense – it’s way easier to build a skyscraper when the bricks are already there. Alex: Precisely! Innovation doesn’t have to start from zero. It's about connecting the dots—whether those dots come from history, chance discoveries, or cross-disciplinary conversations.

Human-Centric Innovation

Part 4

Alex: Building on the idea of learning from the past and those unexpected discoveries, let's talk about how understanding people’s behaviors and emotions can “really” drive innovation. This leads us to human-centric innovation, where we focus on the end-users themselves. It's about creating solutions that genuinely resonate with people on emotional, cultural, and practical levels. Justine: So, we're focusing on the actual users now. Makes sense, right? You can’t just launch a product and hope it sticks. But how do you even start to truly get people? I mean, they don't exactly walk around with signs saying, "Here are my deepest needs." Alex: That's where observational techniques, like ethnography, come in. Ethnographic research is all about immersing yourself in the lives of your consumers. You’re watching how they interact with products, what frustrates them, what excites them—understanding them in their real-world context. It’s way more insightful than just asking people what they think in a survey or focus group. Justine: Why is that, though? Are people just bad at knowing—or admitting—what they really need? Alex: Exactly! People’s stated preferences can be pretty superficial. What “really” drives consumer behavior often happens below the surface—in the realm of emotions, memories, and cultural stuff. Kaye uses a great example about chocolate. People might say they prefer dark or milk chocolate. But if you dig a little deeper, milk chocolate often triggers feelings of warmth, nostalgia, childhood comfort...you know, those memories of unwrapping a candy bar. Dark chocolate, on the other hand, tends to signal sophistication, health-consciousness, a more adult identity. These emotional undercurrents guide their choices, even if they don't realize it. Justine: So, someone grabbing dark chocolate might be less about the taste and more about feeling cosmopolitan or something. And milk chocolate eaters just want a hug through a snack. I can relate. Alex: Exactly! It’s less about the product itself, more about the emotional and cultural framework it connects to. Traditional methods often miss that. They fail to capture those unspoken emotions and habits. Ethnography lets you uncover these subtleties by observing real behavior rather than relying on what people tell you. Justine: Okay, I’m convinced that actions speak louder than words. But what happens when those actions reveal things we didn’t see coming? What if people are using your product in ways it wasn’t designed for? Alex: That’s often a goldmine for innovators. When you see people improvising or “hacking” a product, that highlights unmet needs. Take the example of Cascade, the dishwashing detergent. When regulations reduced phosphates in their formula, customers noticed it wasn't working as well. People got frustrated and started sharing DIY solutions online—customizing their washing routines to make up for it. Cascade watched these adaptations and redirected their product development to address those challenges, improving their product in the end. Justine: So, the customers basically did the R&D for them. It’s like when gamers mod a video game to fix bugs the developers missed. It's frustrating for the consumer, sure, but if the company's paying attention, they can turn those adaptations into something better. Alex: Right. It's about seeing consumer ingenuity not as criticism but as a resource. Another example is Intel's anthropologist, Genevieve Bell. She studied families to see how tech fit into their routines. What she found wasn’t the neat, idealized uses companies imagine. It was messier, full of shared devices, misplaced gadgets, and workarounds. By understanding those real-world complexities, Intel made products that felt more intuitive and aligned with how people actually lived. Justine: So, instead of forcing consumers to use something "correctly," you design around how they're already interacting with it. I get it. But it can’t be a one-size-fits-all approach, right? Culture has to complicate things. Alex: Oh, absolutely. To innovate successfully, you have to understand not just the individual but the broader cultural and social landscape they’re part of. A great example is Dove’s “Campaign for Real Beauty.” It broke with traditional ads and celebrated diversity. It featured women of different sizes, shapes, and ethnic backgrounds. It deeply resonated with audiences because it reflected their realities. It wasn’t just a campaign; it was a cultural statement. Justine: That campaign's iconic now. What made it innovative wasn't just the message—it's that Dove realized its consumers weren't buying into the same old beauty standards anymore. They tapped into a cultural shift. Alex: Precisely. Cultural sensitivity amplifies emotional resonance, making products or campaigns feel personal. Another example is how the kitchen has evolved to be not just for cooking but the heart of family decision-making and bonding. Companies that innovate around this expanded role—offering designs that support organization, connection, or multitasking—capture not just practical needs but emotional ones, too. Justine: So, understanding people involves a mix of watching, listening, and appreciating their worlds. But what happens when people innovate on their own, without the company watching? Are DIY hacks a nuisance, or do they hold potential for reshaping markets? Alex: A little of both, but mainly the latter. Grassroots innovation, consumer-created innovation...it’s a treasure trove. Everyday people are natural problem-solvers. I heard about a parent who hacked their GPS to find their household items—it wasn’t about directions; it was about solving their family’s biggest problem: losing things. Justine: So, the next big product might already be sitting in someone's Frankenstein creation. Paying attention to those hacks opens up new pathways, I see. Alex: Exactly. That's why those ethnographic interviews—observing people in their own environments—are so valuable. They reveal motivations that focus groups often miss. And it’s not just about fixing problems; it's about seeing the underlying "why" in how consumers interact with products. Those insights are often the blueprint for big innovations. Justine: Human behavior might be messy, but that's clearly where the most exciting ideas come from. It’s a mix of watching, learning, and sometimes just being surprised by how people defy expectations. Fascinating stuff.

Conclusion

Part 5

Alex: Okay, so to bring everything together, we’ve been exploring Debra Kaye's “Red Thread Thinking” and really digging into what innovation is all about. We started by clarifying the difference between creativity, which is that initial spark of an idea, and innovation, which is actually turning that idea into something that makes a real difference. Then, we talked about how looking back at the past and being open to those unexpected, serendipitous moments can lead to some really fresh breakthroughs, even from things that seem like failures. And lastly, we emphasized how important it is to put people at the center of innovation—really understanding their feelings, behaviors, and cultural backgrounds—so that what you create actually resonates with them. Justine: Right, and I think the key takeaway for me is that innovation isn’t some kind of magical, rare event. It’s more like tackling a huge puzzle. You’ve got to find the right pieces—creativity, historical context, insights into people—and then figure out how they all fit. It’s not just about coming up with something new and shiny; it’s about making that new thing matter. Alex: Absolutely, and making it matter requires curiosity, empathy, and creating an environment where exploration is encouraged and resilience is valued. The real lesson here is to look past what's right in front of you. The ideas, solutions, and even those "failures" you see might just need a fresh perspective or a different context to unlock their potential. Justine: Exactly! So, whether you're rethinking old ideas, capitalizing on those happy accidents, or just watching how people actually use your products, the trick is to stay curious and observant. Innovation is all around us; it’s just waiting for someone to connect the dots, or as Debra Kaye calls it, connect the "Red Threads." Alex: Exactly! So, let's challenge our listeners with this: start looking at the world around you as a network of connections. What ideas, objects, or behaviors can you reimagine and recombine into something totally new? The threads are already there; it’s really up to you to weave them together. Justine: And really, if you are feeling stuck, just remember the story of Post-it Notes. They started as a complete adhesive failure. So there is always potential to be found, even in the unexpected. Until next time, everyone, keep finding those red threads!