How Fame Killed Elvis, Lennon & Ali

13 minGolden Hook & Introduction

SECTION

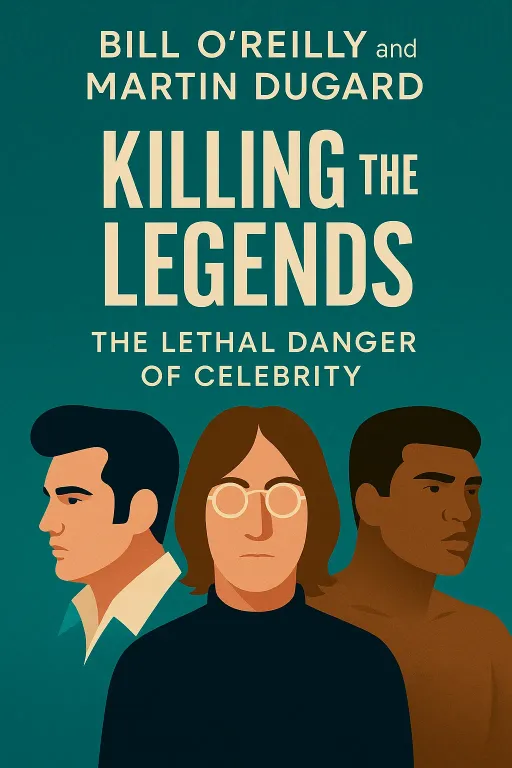

Olivia: Okay, Jackson. You're on the spot. Give me your five-word review of the book we're talking about today. Jackson: Hmm, five words. I've got it: "Legends die, contracts live forever." Olivia: Wow, that's bleak. And accurate. Mine is: "Fame's a killer, literally." Jackson: Oof. That pretty much sets the tone, doesn't it? It feels like we're about to walk into a tragedy. Olivia: We are, three times over. And that perfectly sums up the book we're diving into today: Killing the Legends: The Lethal Danger of Celebrity by Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard. Jackson: Ah, the 'Killing' series guys. They have a very specific, dramatic, almost thriller-like way of telling history, and this one got some pretty polarizing reviews from readers for its central idea. Olivia: Exactly. Their whole argument is that for Elvis Presley, John Lennon, and Muhammad Ali, fame wasn't just a perk—it was a fatal condition. They argue that each of them, in their own way, surrendered their autonomy to others, and that decision sealed their destinies. Jackson: A surrender of autonomy. That's a powerful frame. It’s not just about bad luck or bad choices, but a loss of control. Olivia: Precisely. And the book opens with maybe the most potent example of that loss of control: the final, lonely moments of the King of Rock 'n' Roll.

The King's Cage: Elvis Presley and the Surrender of Autonomy

SECTION

Olivia: The book paints this absolutely devastating picture. It's August 16, 1977. Elvis Presley, the man who once electrified the world, is found dead on the floor of his Graceland bathroom. He's 42, but the book describes him as a "garish caricature of himself: swollen, obese, and often unable to remember lyrics due to a barbiturate addiction." Jackson: It’s such a jarring image. This is the guy who made the world swoon, the symbol of rebellion and charisma. How does a person with that much power and adoration end up dying so alone and in such a state? Olivia: That’s the central question the book tackles. And the answer it provides isn't simple. It points a finger not just at Elvis, but at the entire system built around him, a system personified by one man: Colonel Tom Parker. Jackson: The infamous manager. I know he was controlling, but the book really frames him as the architect of Elvis's downfall, right? Olivia: Completely. The authors portray Parker as a master manipulator with a shady past—he was an illegal immigrant from the Netherlands, which is why Elvis, one of the biggest stars on the planet, never toured internationally. Parker couldn't get a passport and risk being deported. Jackson: Wait, hold on. Elvis never played a show outside of North America because his manager was an illegal immigrant? That's insane. Olivia: It is. And that's just the start. Parker's control was absolute. He pushed Elvis into a relentless grind of formulaic, low-quality movies because they were a predictable cash cow. The book details the filming of Clambake, a movie Elvis openly despised. He was gaining weight, he was miserable, and he actually had a huge fight with Parker about it. But Parker’s response was essentially to keep the machine running. Jackson: So Elvis was creatively stifled. But lots of artists deal with bad management. What about the drug use? Isn't that ultimately on him? Olivia: It is, and the book doesn't absolve him. But it argues that a compliant, drugged Elvis was a profitable Elvis. The authors present this staggering piece of data: in the first seven months of 1977 alone, his personal physician, Dr. George Nichopoulos—or Dr. Nick—prescribed him over ten thousand doses of sedatives, amphetamines, and narcotics. Jackson: Ten thousand doses? In seven months? That’s not a prescription; that's an assembly line. He wasn't being treated; he was being enabled. Olivia: He was being managed. His entourage, the "Memphis Mafia," was on the payroll. Dr. Nick was on the payroll. Colonel Parker was taking a massive cut. Everyone had a vested interest in keeping Elvis just functional enough to perform, but not healthy enough to question the arrangement. He was trapped in a gilded cage, and the bars were made of money, fame, and prescription pads. Jackson: It’s a story of implosion, then. He was consumed from the inside out by the very empire he built. I remember the book mentioning the one time he met the Beatles. Was the decline already visible then? Olivia: Oh, absolutely. The book describes that 1965 meeting as incredibly awkward. The Beatles idolized him, but when they met him, he was making these soft, cheesy movie-musicals. John Lennon apparently asked him point-blank, "What happened to good old rock and roll?" Paul McCartney later reflected that it was sad, that the styles were changing in their favor and Elvis was being left behind. He was already becoming an oldies act, isolated from the very culture he helped create. Jackson: Wow. So he lost control of his art, his finances, and ultimately, his own body. It’s a chilling story. But it’s a very different kind of "killing" from what happened to John Lennon. Olivia: A completely different kind. Elvis’s danger came from within his own bubble. Lennon’s came from the outside world, a world that was obsessed with him.

The Walrus's War: John Lennon and the Price of a Public Voice

SECTION

Jackson: Right. Lennon's story feels more direct. He was assassinated. But the book's title is Killing the Legends, plural. How do the authors connect his murder to this broader theme of celebrity being a lethal condition? It wasn't an overdose or a slow decline. Olivia: The book argues that Lennon was killed because he was a celebrity, and specifically because of the gap between his public persona and his private life. His murderer, Mark David Chapman, was a deranged fan who became obsessed with what he saw as Lennon's hypocrisy. Jackson: The "more popular than Jesus" comment, the "Imagine no possessions" lyric from a man living in a luxury apartment at the Dakota. That's what fueled Chapman's rage? Olivia: That's the argument. Chapman saw Lennon as a "phony," and in his twisted mind, that betrayal was a capital offense. So Lennon’s fame, his global platform, is what made him a target. But the book goes deeper, suggesting the "killing" of John Lennon was a process that started years earlier. Jackson: What do you mean? Olivia: It points to the immense pressure of being a Beatle and the internal fractures that fame caused. The book uses the famous rooftop concert in 1969 as a perfect example. It looks like this cool, rebellious moment, but in reality, the band was falling apart. Jackson: I love that scene from the documentary. It feels so free. Olivia: On the surface, yes. But the book describes the tension in the room. Yoko Ono is a constant, disruptive presence. George Harrison is annoyed. Paul is trying to hold it all together. And John, who was deep into heroin at the time, ends the performance with that iconic, sarcastic line: "I'd like to say thank you on behalf of the group and ourselves, and I hope we've passed the audition." Jackson: "Passed the audition." Wow. It sounds like a joke, but he's really saying, "Is this it? Are we done?" Olivia: Exactly. The pressure had fractured them. And after the Beatles, Lennon's fame didn't wane; it transformed. He and Yoko became these figureheads of the peace movement, which put them on a collision course with another powerful force. Jackson: The U.S. government. Olivia: Richard Nixon's administration. The book details how the FBI put Lennon under surveillance. They were terrified his anti-war activism would mobilize young voters and cost Nixon the election. There were serious efforts to deport him. So his celebrity voice, the very thing that gave him influence, also made him an enemy of the state. Jackson: So he was being attacked from all sides. From the government, from the public, and from his own inner demons with addiction. It’s a very different picture from Elvis, who was isolated from the world. Lennon was in a war with the world. Olivia: A perfect way to put it. And his relationship with Yoko was his fortress in that war. But the book portrays it as a deeply co-dependent one that further isolated him from his bandmates and even his own son, Julian. It was all-consuming. Jackson: It’s a story of external forces, then. Where Elvis was killed by the people meant to protect him, Lennon was killed by the consequences of his own global reach. Which brings us to Muhammad Ali, whose story is different yet again. Olivia: Yes. Ali’s "killing" wasn't a single event. It was a slow, brutal, and very public process, inflicted by the one thing that made him a legend: the boxing ring.

The Greatest's Burden: Muhammad Ali and the Physical Cost of Glory

SECTION

Olivia: The book zeroes in on the "Thrilla in Manila," his third fight against Joe Frazier in 1975. It's often hailed as one of the greatest boxing matches in history, but the authors frame it as something much darker. They describe it as an act of mutual destruction. Jackson: I’ve seen clips. It was absolutely brutal. Olivia: Brutal doesn't even cover it. The fight was in a coliseum with a tin roof and broken air conditioning, under scorching TV lights. It was fourteen rounds of pure punishment. Ali later said, "It was like death. Closest thing to dyin’ that I know of." Jackson: And he almost quit, right? Olivia: He did. Between the 14th and 15th rounds, he told his corner to cut his gloves off. He was done. But across the ring, Frazier's trainer, Eddie Futch, saw that Frazier's eyes were swollen shut and made the decision to stop the fight, saving Frazier from further harm and, ironically, handing Ali the victory. Jackson: Wow. So Ali won because his opponent's corner was more concerned about their fighter's life than Ali's corner was about his. Olivia: It's a stark way to look at it, but the book supports that view. And this is where the theme of losing autonomy comes in for Ali. After that fight, his own doctor, Ferdie Pacheco, saw the damage being done—especially to his kidneys—and begged him to retire. Jackson: But he kept fighting. Why? He was the heavyweight champion of the world. He was "The Greatest." What more did he need? Olivia: Money. The book paints a picture of a massive financial machine around Ali, managed by Herbert Muhammad of the Nation of Islam. Ali had huge expenses—multiple families, a large entourage, taxes. The machine needed to be fed. So, despite his doctor's warnings, Ali fought on. Pacheco actually quit Ali's team in protest, saying he didn't want to be an accomplice to a "manslaughter." Jackson: That’s a powerful statement. But again, isn't that just the nature of boxing? You get paid to take punches. How is that a unique "lethal danger of celebrity"? Olivia: The book's argument is that Ali's celebrity status created a financial empire that demanded he sacrifice his body for the brand. He wasn't just a boxer; he was Muhammad Ali, a global icon. The paydays were too big to turn down. He was pressured to keep fighting long past his prime, absorbing hundreds of thousands of blows that almost certainly contributed to his Parkinson's disease. He was, in effect, being killed by the very profession that made him a legend. Jackson: So, he lost control of his own health in the service of his own legend. Elvis lost control to his manager, Lennon to the world's obsession, and Ali to the demands of his own brand. Olivia: That's the thread connecting them all. Three different paths, but the same tragic destination: a loss of self, a surrender of control, all under the crushing weight of being a legend.

Synthesis & Takeaways

SECTION

Jackson: It's a really dark take on fame. When you put all three stories together, the book's thesis that celebrity is a "lethal danger" feels less like a controversial opinion and more like a documented pattern. Olivia: It really does. The core insight of Killing the Legends is that for these three men, fame wasn't a destination; it was a trap. It eroded their autonomy. Elvis ceded control to his manager and his addictions. Lennon ceded control to his public persona and his all-consuming partnership with Yoko. And Ali ceded control to the financial machine that demanded he keep fighting. In each case, that loss of control is what proved lethal. Jackson: They became products, managed and consumed until there was nothing left. Elvis lost control of his body, Lennon of his safety, and Ali of his future health. Olivia: Precisely. The book forces you to look past the iconic images—the swiveling hips, the round glasses, the boxing gloves—and see the vulnerable human beings who were, in many ways, victims of their own success. Jackson: It definitely makes you think about celebrity culture today. In an era of social media, where fame is more accessible but also more fleeting and intense, has that lethal danger gotten worse? Are we just creating more legends to watch them fall? Olivia: That is the million-dollar question, isn't it? It’s a powerful and unsettling thought to end on. We’d love to hear what you think about this. Does fame today carry the same dangers, or have things changed? Join the conversation on our socials and let us know. Jackson: It's a conversation worth having. This was a heavy one, but incredibly insightful. Olivia: This is Aibrary, signing off.