Jim Crow & The Space Race

11 minThe American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race

Golden Hook & Introduction

SECTION

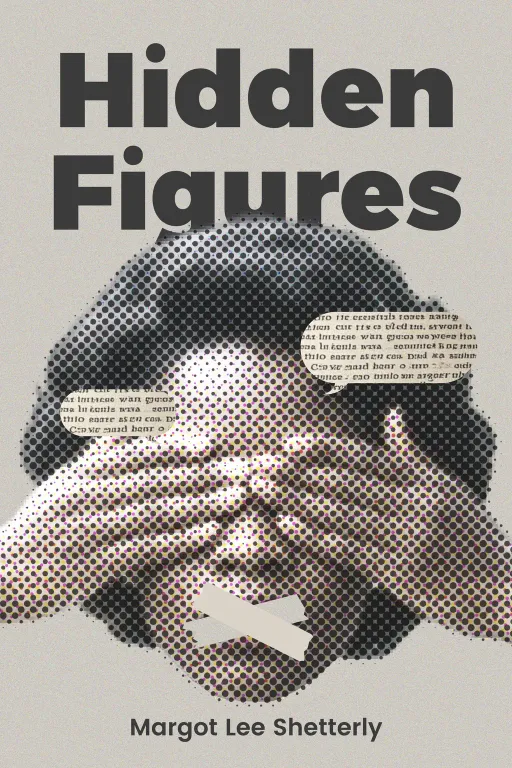

Michael: The race to the moon wasn't won in a gleaming mission control room. It started in a segregated, back-room office, with pencils, paper, and a group of brilliant Black women who were treated as second-class citizens. Kevin: That’s a wild image. We all have this picture of the space race—the heroic astronauts, the guys in white shirts with pocket protectors. The idea that the foundational math was being done under Jim Crow rules is just… it’s a lot to process. It’s almost like a secret history. Michael: It was, for a very long time. And that's the world we're diving into with Margot Lee Shetterly's incredible book, Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race. Kevin: What's amazing is that the author, Shetterly, grew up in Hampton, Virginia. Her dad was a NASA scientist. She knew these families her whole life but didn't know the full story. It was literally hidden in plain sight. Michael: Exactly. And that's our first big idea: the paradox of how a national crisis created an unprecedented, yet deeply flawed, opportunity for these brilliant women. It wasn't an enlightened decision; it was a desperate one.

The Paradox of Opportunity

SECTION

Kevin: Okay, so what was the crisis? What forced the hand of an institution that was, by all accounts, deeply entrenched in the segregated South? Michael: In a word: war. World War II. In the early 1940s, America was in a frenzy to build the most dominant air force on the planet. The slogan at the Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory, the predecessor to NASA, was "Victory through airpower!" Kevin: Right, the whole industrial might of America kicking into gear. Michael: Precisely. But they had a massive problem. They were drowning in data from wind tunnel tests and flight experiments, and they were desperately short on people who could process it. We're talking a severe labor shortage. The head of personnel, a man named Melvin Butler, sent an urgent telegram in May 1943 asking for 100 Junior Physicists and Mathematicians, 100 Assistant Computers… the list goes on. They were running three shifts a day, six days a week. Kevin: And I’m guessing the usual pool of candidates—white men—was a bit preoccupied with fighting overseas. Michael: Exactly. So they started looking elsewhere. First, they began hiring white women in large numbers to be "computers." This was already a shift, as many male engineers were skeptical that women could handle the rigorous math. But the women proved to be incredibly skilled, sometimes even better than the engineers they worked for. Kevin: But that still doesn't explain how African-American women got in the door. This is Virginia in the 1940s. Michael: Here’s where the story gets even more complex. It wasn't just the war abroad; there was a battle brewing at home. A. Philip Randolph, a powerful Black labor leader, was furious that the booming defense industry was shutting out African Americans. He threatened to organize a march of one hundred thousand Black people on Washington. Kevin: Wow. That’s a serious threat, especially in the middle of a war. Michael: It was. President Roosevelt was terrified of the optics. So, in 1941, he signed Executive Order 8802, which banned racial discrimination in the defense industry. It was a pragmatic move to prevent a domestic crisis, but it cracked the door open. It meant that Langley, a federal defense agency, could no longer legally refuse to hire qualified Black applicants. Kevin: So this wasn't an act of progressive hiring, it was an act of desperation, legally mandated. Michael: That’s the paradox. And to see how this played out on a human level, you have to look at the story of Dorothy Vaughan. In 1943, she was a brilliant, college-educated math teacher at an all-Black high school in Farmville, Virginia. Kevin: A respected position in her community, I’d imagine. Michael: Absolutely. Teachers were seen as leaders. But the pay was abysmal. Black teachers in Virginia earned almost 50 percent less than their white counterparts. Dorothy Vaughan's annual salary was $850. Kevin: Eight hundred and fifty dollars. For a year. That’s… I have no words. Michael: To make ends meet, she took a summer job at Camp Pickett, a nearby military base. She wasn't teaching. She was working in the laundry, in the boiler plant. It was hot, grueling, monotonous work. But it paid better than her teaching job. Kevin: That is just a brutal indictment of the system. A gifted mathematician, forced to do laundry to support her family. Michael: But then, she saw a job posting. A bulletin for a mathematical job at a federal agency in Hampton. The Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory. The position was for a "computer," grade P-1. The annual salary was $2,000. Kevin: More than double her teaching salary. That’s life-changing money. Michael: It was the difference between scraping by and providing a real future for her four children. So she applied. And a few months later, she got the offer. She had to leave her home, her husband, her children, and move to Newport News for a job that was only guaranteed for "the duration of the present war." But she took it. That's how the first of our hidden figures got to Langley. Not because of a grand gesture of equality, but because of a world war, a labor crisis, and her own determination to seize a sliver of an opportunity.

The Double Victory

SECTION

Kevin: Okay, so they get in the door because of the war. But what was it actually like once they were inside? I can't imagine it was a warm welcome. Michael: Far from it. This is where the second core idea of the book comes in, a concept that was central to the Black community during the war: the "Double V." Kevin: Double V? What’s that? Michael: Victory over the Axis powers abroad, and victory over racism at home. Black newspapers like the Pittsburgh Courier championed this idea. They were saying, "We will fight for our country, but we will also fight for our own rights and dignity within it." And the women at Langley lived this every single day. Kevin: So they’re performing these critical calculations for the war effort, but they’re still subject to Jim Crow laws inside the laboratory? Michael: Yes. When Dorothy Vaughan and the other Black women arrived, they weren't integrated with the white computers. They were assigned to a separate, segregated unit called the West Area Computing section. They were often housed in a less-desirable building on the West Side of the campus, which was seen as the "colored" side. They had to use separate bathrooms and, most famously, a separate table in the cafeteria. Kevin: That’s just infuriating. To be fighting for "freedom" and have to deal with that level of petty, demeaning racism at your own lunch table. Michael: And this brings us to one of the most powerful, quiet stories of defiance in the entire book. In the main cafeteria, the management placed a small, wooden sign on a table in the back that read: "COLORED COMPUTERS." Kevin: Oh, come on. Michael: It was a daily, public humiliation. A reminder of their second-class status. Most of the women just endured it, not wanting to make waves and risk their jobs. But one woman, Miriam Mann, refused. Michael: Every day, she would walk into the cafeteria, see the sign, and she would pluck it off the table and slip it into her purse. Kevin: Just like that? No announcement, no confrontation? Michael: None. Just a quiet act of removal. The next day, a new sign would be there. And the next day, Miriam would take that one, too. This went on for weeks. Her friends were nervous for her, but she just kept doing it. It was her personal battle in the Double V campaign. Kevin: That takes such incredible courage. It’s not a loud protest, but it’s a powerful refusal to accept humiliation. It’s like a workplace protest of one. Michael: It is. And eventually, one day, the sign just stopped appearing. Miriam won. No one ever acknowledged it, but the sign was gone for good. It’s a small story, but it’s a perfect metaphor for their entire experience. They weren't just calculating aerodynamic forces; they were calculating the human cost of dignity and pushing back, inch by inch. Kevin: And this was the environment where Dorothy Vaughan eventually became a supervisor? That seems like a monumental leap. Michael: It was. And it happened under tragic circumstances. The white woman who was the head of West Computing, Blanche Sponsler, suffered a severe mental breakdown and sadly passed away. For a while, the unit was leaderless. But Dorothy Vaughan, with her natural leadership and sharp mind, had already become the de facto head. In 1949, management finally made it official. They appointed her acting head of West Computing, making her NACA’s first-ever Black supervisor. Kevin: Wow. So even her promotion, a huge step forward, comes out of this segregated system. She could only be a supervisor of the "colored" unit. Michael: Exactly. It was both a massive personal achievement and a reflection of the ceiling that was still firmly in place. She was breaking barriers, but within a world that was still defined by them.

Synthesis & Takeaways

SECTION

Michael: So when you put it all together, you have this incredible contradiction. America's technological manifest destiny, this push to conquer the skies and then space, is literally being fueled by women who are simultaneously being denied basic dignity on the ground. Kevin: It forces you to redefine what 'patriotism' or 'contribution' even means. They were fighting for the country's future while also fighting for their own share of the American dream, right there in the Langley cafeteria with a wooden sign. Michael: The book is so powerful because it doesn't just celebrate their mathematical genius. It celebrates their resilience. It shows that their fight for equality wasn't separate from their work; it was intertwined. Every calculation they made, every barrier they pushed against, was part of the same effort. Kevin: And it’s not ancient history, is it? The book was only published in 2016, and it became this massive bestseller and an Oscar-nominated movie because, I think, we all instinctively know this story isn't over. Michael: That’s right. The author herself said she wrote it to integrate these women into the main narrative of American history, not as a separate story at the margins, but as protagonists at the very center. Kevin: It makes you think, what talent are we overlooking today because of our own blind spots? What modern-day "hidden figures" are out there, in all sorts of industries, whose contributions are being ignored because of some invisible version of that "colored computers" sign? Michael: It's a powerful question. And it’s why this book feels so urgent. It’s a history lesson, but it’s also a mirror. Kevin: It really is. We'd love to hear your thoughts. What 'hidden figures' have you seen in your own lives or fields? Let us know. It’s a conversation worth having. Michael: This is Aibrary, signing off.