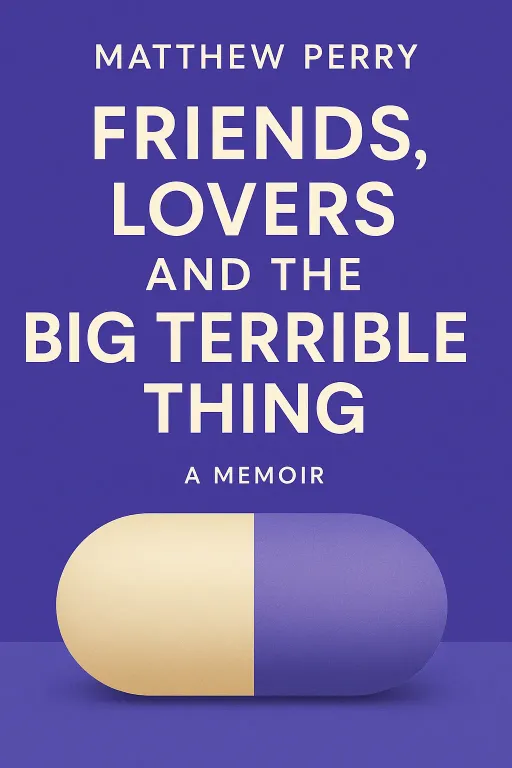

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing

10 minA Memoir

Introduction

Narrator: At the height of his fame, Matthew Perry was the witty, charming, and universally beloved Chandler Bing, a cornerstone of the most successful sitcom in television history. To the world, he had everything: a million-dollar-per-week salary, a dream house with a view, and the adoration of hundreds of millions of fans. But behind the scenes, a different story was unfolding. At forty-nine years old, he lay in a hospital bed, his body tethered to an ECMO machine that was breathing and pumping blood for him. His colon had exploded from opiate abuse, and doctors had given his family the grim news: he had a two percent chance of surviving the night. How could the man who made the world laugh be secretly living a life of such profound pain and desperation?

In his unflinchingly honest memoir, Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing, Matthew Perry pulls back the curtain on his life, revealing the harrowing reality of his lifelong battle with the disease of addiction. It’s a story that dismantles the illusion of fame, exposing the deep-seated loneliness and fear that no amount of success could cure, and chronicles a brutal, decades-long fight for survival.

The Faustian Bargain for Fame

Key Insight 1

Narrator: Long before he became a household name, Perry was a young man grappling with deep-seated feelings of inadequacy and a desperate need for external validation. Haunted by a childhood fear of abandonment, stemming from being flown alone between his divorced parents as an "unaccompanied minor," he came to believe that fame was the ultimate solution. If he could just become famous, he thought, all the holes inside him would be filled. This belief culminated in a desperate, defining prayer. Alone and on his knees, he said, "God, you can do whatever you want to me. Just please make me famous."

Three weeks later, he was cast as Chandler Bing. The prayer was answered with a speed and magnitude he could never have imagined. Friends wasn't just a hit; it was a cultural phenomenon. The cast became global superstars, and Perry had everything he had ever wished for. Yet, the fame, the money, and even a high-profile relationship with Julia Roberts couldn't silence the internal voice telling him he wasn't enough. The bargain had been struck, and he soon discovered that while God had granted his wish for fame, the "do whatever you want to me" clause would be exacted with a terrible price. Fame wasn't the answer; it was just a bigger, brighter stage for his inner turmoil.

The Duality of Chandler Bing

Key Insight 2

Narrator: Perry’s life during the Friends era was a study in stark contrasts. On-screen, he was the master of the sarcastic one-liner, his unique, off-kilter delivery becoming a cultural touchstone. As his co-star Lisa Kudrow notes in the foreword, even with everything he was battling, "that guy...whip smart...charming, sweet, sensitive...was still there." He was the one who made the entire cast laugh during a grueling late-night fountain shoot for the opening credits.

But off-screen, he was living in a private hell. His addiction, which began in earnest after a doctor gave him a Vicodin for a jet ski accident, spiraled. He confesses to the absurdity of being at the height of his career, marrying Monica on the show, and being driven back to a rehab facility by a technician right after filming the scene. The cast knew he was in trouble—Jennifer Aniston was one of the first to confront him, a moment he describes as "devastating"—but they couldn't grasp the full extent of his disease. He became a master of hiding his condition, terrified that if the audience knew, they wouldn't find him funny anymore. This duality defined his existence: the beloved friend to millions and a man desperately, and secretly, fighting for his life.

The Full-Time Job of Addiction

Key Insight 3

Narrator: The memoir makes it painfully clear that addiction is not a part-time habit; it’s an all-consuming, full-time job. Perry’s pursuit of drugs and alcohol became the organizing principle of his life. He details the elaborate and often humiliating lengths he went to in order to feed his disease. He would meticulously plan his Sundays around attending real estate open houses, not to buy a home, but to raid the medicine cabinets of unsuspecting strangers for pills.

His addiction was a relentless cycle of calculation and desperation. During one period of filming in New York, he would have sober companions with him, yet he would secretly call room service and have them hide a bottle of vodka in the bathtub. He would drink the entire bottle just to stop the shaking and feel "normal" for a few hours, only to wake up and start the agonizing process all over again. He was taking up to fifty-five Vicodin a day, a dosage that should have been lethal. His mind, as he puts it, was "out to kill him," and he knew it.

The Price of the Ticket

Key Insight 4

Narrator: Perry’s memoir does not shy away from the brutal, physical toll of his addiction. The "Big Terrible Thing" wasn't just a metaphor; it manifested in a series of catastrophic health crises that nearly killed him. The most harrowing is the story of his exploding colon. Years of opiate abuse had led to severe gastrointestinal problems, culminating in a perforation that sent him into septic shock and a two-week coma. He was one of only five people ever to be put on an ECMO machine for that condition at that hospital—the other four died.

He survived, but woke up with a colostomy bag, a physical reminder of his brush with death that he would have for nine months. This was not his only near-death experience. In a Swiss rehab facility, a routine pre-surgery injection of Propofol stopped his heart for five minutes. A "beefy Swiss guy" performed CPR so aggressively that he saved Perry's life but broke eight of his ribs. These visceral, life-altering events serve as the book's most powerful warning, illustrating that the price of addiction is paid not just in lost opportunities and relationships, but with one's own body.

Finding Purpose in the Wreckage

Key Insight 5

Narrator: After decades of failed rehabs, broken relationships, and near-death experiences, Perry began to confront the question that echoed through his survival: "Why am I alive?" The answer didn't come from fame or fortune, but from a place of service. He describes a profound spiritual experience during a moment of intense desperation, where he prayed for help and was met with a feeling of a warm, golden light and an overwhelming sense of love and acceptance. He says, "I stayed sober for two years based on that moment."

This experience shifted his focus. He realized that his purpose was not to be a famous actor, but to be a man who could help others. He writes, "When a man or woman asks me to help them quit drinking, and I do so, watching as the light slowly comes back into their eyes, that’s all God to me." This newfound purpose became his anchor. He recognized that he had to get famous to learn that fame wasn't the answer, and that he had to nearly die to finally want to live. His reason for writing the book, he makes clear, is to be of service—to let others who are struggling know that they are not alone.

Conclusion

Narrator: The single most important takeaway from Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing is that addiction is a patient, cunning, and democratic disease. It does not care about fame, wealth, or talent. It can hide in plain sight, behind the brightest of smiles and the sharpest of wits, slowly and methodically dismantling a life. Matthew Perry’s story is a brutal testament to the fact that external success is a fragile shield against internal pain, and that true recovery is not about willpower, but about surrender, connection, and finding a reason to live that is bigger than oneself.

Ultimately, the book is a profound act of service, the fulfillment of the purpose Perry found in his darkest moments. It challenges us to look past the polished facade of celebrity and see the human being underneath, and to extend compassion to those who are fighting battles we cannot see. Perry leaves the reader with a message of hard-won hope, reminding us that our scars are not a sign of weakness, but proof that a battle was fought and, against all odds, won. And in the face of our own "Big Terrible Things," he offers a simple, powerful question: "What would Batman do?"