Escape the Doom: See the World Clearly

Podcast by The Mindful Minute with Autumn and Rachel

Ten Reasons We're Wrong About the World — and Why Things Are Better Than You Think

Escape the Doom: See the World Clearly

Part 1

Autumn: Hey everyone, welcome back! Let me start with a question: when you look at the world today—you know, poverty, health, education—do you instantly think things are just… falling apart? Don't worry, you're not alone if you do. Most of us tend to have these quick, negative assumptions. Rachel: Yeah, Autumn, but isn't that just… well, reality? I mean, the news is hardly full of sunshine and rainbows, is it? Are we about to find out it’s all been one big overreaction? Autumn: Actually, in a way, yes! That's exactly what Hans Rosling’s “Factfulness” is all about. It dives into why we often misjudge the state of the world, and it reveals a surprising truth: a lot of the things we think are getting worse—like, say, global poverty or public health—are actually getting better. The book uncovers ten cognitive instincts that distort our perception and replaces all that negativity with curiosity, humility, and… believe it or not, actual hope! Rachel: Ten instincts, huh? Sounds like my brain's been working overtime to make things worse than they are. So, what exactly are we going to unpack today? Autumn: We're breaking it down into three parts. First, we'll explore these cognitive biases that cloud our judgment—those mental traps that make the world look so much bleaker than it is. Next, we’ll uncover the tools Rosling gives us to help see the world more clearly, all backed by data and some pretty cool visualizations. And finally, we'll talk about the habits and strategies we can use to translate all this new knowledge into actions that, you know, actually make a difference. Rachel: Right, so we're putting glasses on humanity's blurry worldview, so to speak. Should be fun—and maybe a bit uncomfortable for me. Let's dive in.

Cognitive Instincts and Misconceptions

Part 2

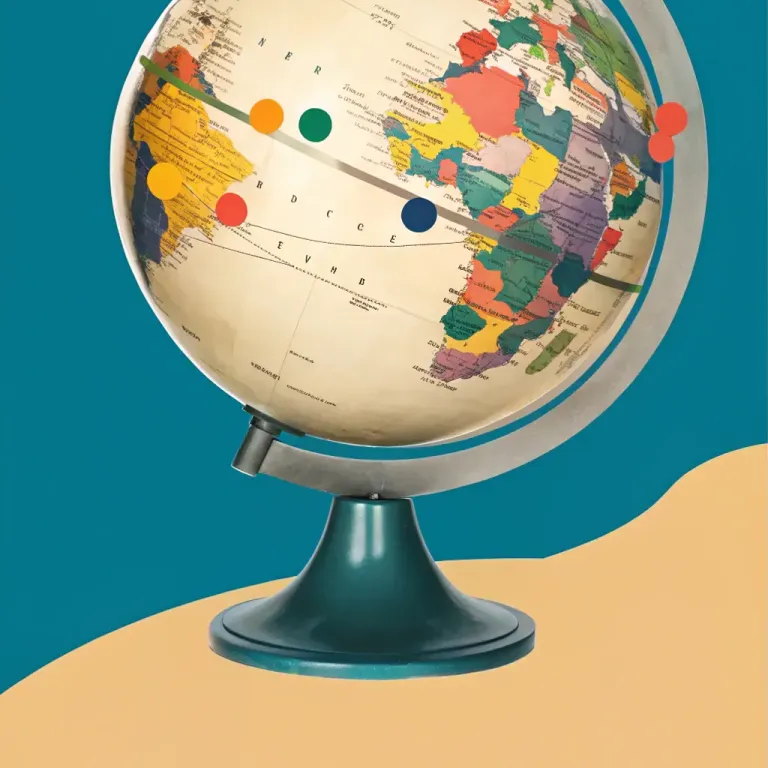

Autumn: Okay, so let's dive right in. At the heart of it, we're talking about cognitive instincts. These are, you know, those mental shortcuts we've developed over generations that were super helpful for survival back in the day. But, in today's complex world, they often lead us astray. They’re the reason we misinterpret information and misunderstand global trends. Hans Rosling identified ten of these instincts, but we're going to focus on three of the big ones today: the Gap Instinct, the Negativity Instinct, and the Fear Instinct. Rachel: Right, got it. Sounds like these are the usual suspects that make everything seem more dramatic than it actually is. So, let's take them one at a time, Autumn. What exactly is this “Gap Instinct” all about? Autumn: Okay, so the Gap Instinct is basically our tendency to simplify everything into two extremes. It's like, rich versus poor, developed versus developing—without really seeing all the shades in between. It's oversimplification taken to the extreme. Rosling explains that this instinct makes us think the world is polarizing when actually, most people are living somewhere in the middle. Rachel: So, yeah, rich and poor isn’t the whole picture. But is this 'middle ground' really big enough to matter? Autumn: Absolutely! One of Rosling's key tools to combat this instinct is his Four Income Levels framework. So, instead of just thinking "rich" or "poor," this framework categorizes people into Levels 1 through 4 based on their income. For example, at Level 1, people are living on less than a dollar a day—that's extreme poverty. Then you've got Level 2, where people are earning like, two to eight dollars a day. You see some improvement in living conditions here, like basic shoes, a bit better sanitation. Level 3 is eight to thirty-two dollars a day—think bicycles, refrigerators, some education. And then Level 4 is full-blown affluence, over sixty-four dollars a day. Rachel: I guess most of us think in extremes because it's just easier. But I’m guessing Rosling has evidence to show that this middle ground is actually where most people are, right? Autumn: Exactly! For example, more than half the world's population lives on Level 2. That's not "poverty" as most people understand it, and nearly 75% of the world is somewhere between Levels 2 and 4. Rosling shares this fascinating example where he asked medical students to estimate child mortality rates around the world. They assumed countries like Malaysia must have sky-high rates because they were, you know, mentally filed under the “poor” category. But guess what? Malaysia's child mortality rates are actually better than Saudi Arabia's. It just completely shattered their assumptions. Rachel: Wow, that's exactly the kind of thing that makes you rethink the whole "developing/developed" idea, doesn't it? Saudi Arabia might have a ton of oil wealth, but Malaysia actually leveraged better health policies. Autumn: Exactly. And that’s the problem with binary thinking—it blinds us to progress and nuance. If we don't have the data to break through that illusion, we keep making decisions based on outdated or just plain wrong perceptions. Rachel: Okay, fine, I'll admit it—I probably have a pretty bad case of the Gap Instinct. But let’s move on. What about the Negativity Instinct? Autumn: Ah, this one's super common too. So the Negativity Instinct is basically our brain's tendency to focus on the bad news. But hey, don't blame yourself for it. It's like, evolutionary wiring. Our ancestors needed to focus on threats to survive. That was great when they were running from predators, but today it makes us zero in on disasters and crises, even when there's a lot of positive progress happening at the same time. Rachel: So, I shouldn’t feel guilty for doom-scrolling—it’s basically caveman brain short-circuiting modern reality. Is this where Rosling starts talking about media sensationalism? Autumn: Bingo. The media really fuels this instinct by prioritizing dramatic, catastrophic stories because those grab our attention. Take global child mortality, for instance. Centuries ago, child mortality rates were shockingly high—almost half of all kids didn’t live to see their fifth birthday. Today, because of advances in healthcare, hygiene, and nutrition, nine out of ten kids survive past five. But instead of celebrating that, people are overwhelmed by media reports that focus on terrible, but isolated tragedies, and that make it seem like things haven't improved at all. Rachel: It's pretty ironic, isn’t it? We’ve got evidence of historic breakthroughs literally changing the course of humanity, but it gets buried under headlines about the latest disaster. Autumn: Totally, and Rosling argues that it creates this damaging illusion of decline, which feeds into hopelessness and despair. He’s not saying we should ignore problems, but understanding the progress helps us approach challenges with hope, and to focus on solutions, rather than just spiraling into fear. Rachel: Okay, so, speaking of fear, what's the deal with the Fear Instinct? Sounds like this one is all about emotional overdrive. Autumn: You nailed it. The Fear Instinct really cranks up perceived threats, especially the ones that trigger strong emotional responses—think violence, pandemics, natural disasters. It’s that primal “fight or flight” response kicking in, and it often distorts reality. Rachel: Let me guess – Rosling's got another great example to illustrate this point? Autumn: Oh, does he ever. Do you remember the Ebola outbreak back in 2014? The world went into a total panic. Media outlets plastered graphs of cases rising exponentially, and it seemed like we were on the verge of a global catastrophe. But, what the data actually showed was that the outbreak was concentrated in a handful of West African countries. With targeted health measures and education, the spread was contained. But because of the fear, countries far from the outbreak implemented extreme policies, like closing borders, instead of directing resources where they were actually needed. Rachel: Classic overreaction, right? Fear goes up, we focus on the wrong things, and then the real problem gets put on the back burner. Sounds like a pretty expensive way to handle crises. Autumn: Exactly, and it's another reason why factual thinking is so important. Fear instincts can lead us to make hasty, or just plain wrong, decisions. When we ground our responses in data, we can manage risks a lot more effectively, without falling victim to knee-jerk panic. Rachel: So, I’m starting to see how all these instincts—Gap, Negativity, Fear—distort our perception of reality. So how do we get out of these traps?

Data-Driven Worldview

Part 3

Autumn: So, building on those cognitive distortions, let's talk about how data and factual evidence can actually help us counteract those biases. That leads us to cultivating a data-driven worldview. It's all about tools and methods for gaining a clearer, more data-informed perspective. Rachel: Okay, so our brains are wired to mess with us. Now you’re saying we need a whole toolbox just to see the world straight? Autumn: Pretty much! Rosling believed that data isn't just boring numbers; it's a superpower. A way to fight those instincts and see reality for what it is. And he really emphasized data visualization. I mean, when you turn raw data into engaging visuals, the patterns and trends just pop out so much more clearly than if you are just staring at numbers in a spreadsheet. Rachel: I’m guessing this is a bit more sophisticated than your average pie chart from a business meeting? Autumn: Oh, totally. A prime example is Gapminder, the data visualization tool Rosling himself developed. It uses interactive bubble charts to compare countries on things like life expectancy, income, and child mortality, and shows how they've changed over time. It's not just eye candy; it actively challenges our preconceived notions. Rachel: Bubble charts, huh? Sounds almost too simple. What's the trick? Autumn: It’s simplicity with depth. For instance, if someone assumes that child mortality is just a fact of life in "developing countries," you can just pull up Gapminder, and boom, that bubble chart smashes that stereotype. You see countries like Malaysia not only holding their own but even outperforming nations we automatically think of as "developed," like Saudi Arabia, when it comes to child mortality rates. Rachel: Wow. Saudi Arabia and Malaysia are not usually in the same sentence, and this flips the script completely. Autumn: Exactly! Plus, watching those bubbles move across decades shows how countries progress, how policies around health, education, and investment really drive change. It proves the world isn't stuck in static categories like "rich" and "poor." It's constantly moving, constantly evolving. Rachel: Okay, those bubbles have my attention. What else has Rosling cooked up? Autumn: He also created Dollar Street, which I think is genius for connecting the dots between numbers and real lives. Instead of just showing global income gaps with numbers, this tool uses photos of homes, kitchens, and belongings at different income levels to show how people actually live. Rachel: Let me guess: this is the "human" side of data? Autumn: Precisely. Say you want to see what life looks like at Level 2, around $2 to $8 a day. On Dollar Street, you’ll find photos of families using jerrycans for water, sleeping on mats. But you'll also see signs of improvement too, like simple shoes instead of bare feet, or maybe a small bicycle that saves them hours of walking. Rachel: So, the visual difference between a $2-a-day household and a $200-a-day household tells a much more powerful story than dry numbers ever could. Autumn: Absolutely. It humanizes big trends. It shows progress without ignoring struggles. It’s one thing to know that billions have escaped extreme poverty. It's another thing entirely to see a Level 3 kitchen with a gas stove instead of an open fire—a real, tangible sign of change. Rachel: I like that. It's like getting an unvarnished look into someone's life, without any extra commentary. Autumn: And that's why it's so impactful. These tools, Gapminder and Dollar Street, they make the abstract concrete. They dismantle that whole "us versus them" mentality and replace it with real understanding. Rachel: Okay, I see how data visualization punches holes in stereotypes. But how do we keep from misusing data? Numbers can be twisted to say almost anything, right? Autumn: Rosling thought about that too. He's a big believer in context is key. Raw numbers don't tell you much without the bigger picture. A classic example is vaccination rates. Rachel: Ah, now we're talking! A health stat with some real meat on its bones. Autumn: More than interesting, it's transformative. Right now, 88% of one-year-olds worldwide are vaccinated against diseases like measles. But most people don’t realize that because the headlines focus on the gaps or setbacks. It's actually a huge public health success story, overshadowed by fear. Rachel: Eighty-eight percent? That's… higher than I thought. Especially in lower-income countries. I figured getting vaccines to everyone would still be a massive challenge. Autumn: It was, and can be. But the data shows steady gains as global campaigns expand access. Think about the eradication of smallpox, a disease that killed millions. Vaccination campaigns wiped it out completely. Polio is headed in the same direction. Rachel: So, pretty much across the board, whether you're Level 2 or Level 4, governments and NGOs are pushing vaccines because that’s one of the most efficient ways to save lives. Autumn: Exactly. It’s data-backed progress in action, governments using trends to target resources where they’re needed most. It’s also a reminder that focusing on long-term progress, not just short-term hiccups, leads to real success. Rachel: Fair point. But you can lose sight of that long-term progress when all you see are the "hiccups." What's Rosling's advice there? Autumn: He suggests three main things. First, always put numbers in context. A stat about infant mortality in one country only really means something when you compare it to its history or to similar countries. Second, follow trends instead of jumping on every isolated event. And third, avoid binary thinking, ditch those "developed/developing" labels and look at the spectrum across Rosling’s Four Income Levels. Rachel: Let me try that out. If I hear about a crisis, like a drought in a Level 1 or 2 country, I should ask how that country has progressed over time rather than assuming it’s doomed, right? Autumn: Precisely! That drought might be devastating, but if it’s happening alongside long-term gains—like better access to wells or irrigation—it paints a more complete picture. It’s progress plus challenges, not just one extreme. Rachel: I’ll admit, switching from "doom-and-gloom mode" to "fact-driven mode" sounds hard, but also pretty fascinating. What's the end game here, though? Autumn: It’s clarity. A data-driven worldview doesn’t ignore the problems, but it offers hope and helps us act more effectively. By understanding trends, acknowledging progress, and questioning our assumptions, we make better decisions. Rachel: Alright, Autumn. I’ll try to trade in my skeptical rants for some bubble charts.

Practical Applications and Personal Growth

Part 4

Autumn: So, with this factual foundation, we can explore how to translate these insights into our daily decisions. This leads us to a topic close to my heart—practical application and personal growth. It’s not just about spotting cognitive biases or admiring clever data visualizations; it’s about cultivating habits that empower us to navigate the world with curiosity, humility, and a bias toward action. And by concluding with concrete steps, we're really tying theory to practice, emphasizing how we can improve both individually and collectively. Rachel: Okay, so what’s the “so what?” of all this? It's great to know that we're wired with faulty instincts and that, apparently, bubble charts can revolutionize our lives. But how do we make this relevant? You know, in a way that truly matters and, preferably, without becoming emotionless data-crunching automatons? Autumn: Well, thankfully, Rosling isn't expecting us to become walking encyclopedias of graphs and stats. His main point is much simpler: to shift our mindset. Start by changing how we approach problems. One of the most actionable takeaways is to consciously replace the urge to blame with a genuine effort to understand the underlying systems. Rachel: Shifting blame to systems, huh? That sounds a little… abstract. Can you give me a concrete example of what that looks like in the real world? Autumn: Sure. Let's take one of Rosling's own experiences. He was investigating why this small Swiss company, Rivopharm, was offering malaria tablets to Angola at an incredibly low price. The immediate reaction was suspicion. It seemed impossible to produce quality drugs at that price point. So, the instinct was to accuse Rivopharm of unethical practices, you know, like underpaying workers or cutting corners on safety. Rachel: Considering it was a pharmaceutical company, I can see why people jumped to that conclusion. Let's be honest; that industry doesn't exactly have a squeaky-clean reputation when it comes to ethics. Autumn: Right, but blaming individuals or isolated companies often oversimplifies a more complex issue. So, instead of rushing to judgment, Rosling investigated further. He discovered that Rivopharm was able to achieve these low costs by using state-of-the-art robotics in their manufacturing process. It wasn't unethical behavior; it was innovation! So, this revelation completely changed the narrative from one of suspicion to one of admiration for their efficiency. Rachel: Okay, so, the lesson here is, don't grab the pitchforks the moment something smells a little fishy. But surely, there are situations where blame is legitimately warranted, right? Autumn: Absolutely! But Rosling argues that focusing solely on blame can often blinker us. If we only focus on assigning blame, we risk missing the chance to truly understand the root causes or to identify innovative solutions within the broader system. Take, for instance, the challenge of low vaccination rates. Would you just blame the parents, or the systemic barriers? Like healthcare infrastructure, education, and affordability. It's not that individual actions are irrelevant. It's that they occur within a complex web of factors that we need to address holistically. Rachel: Alright, fair point. So, don't make people into scapegoats when the problem is more systemic. But let's say I manage to resist the urge to blame. Does that automatically solve the problem? Or is there another pitfall just waiting around the corner? Autumn: Oh, there's definitely another one: the urgency instinct. Remember the Mozambique example? During a health outbreak, local officials panicked and implemented roadblocks to contain the disease. On paper, it seemed logical, right? Stop movement, stop the spread. But in reality, it created chaos. Rachel: Let me guess – making hasty decisions leads to unintended consequences? Autumn: Exactly. So, people couldn't reach hospitals for unrelated emergencies. Others tried to bypass the roadblocks using dangerous shortcuts — like, you know, unsafe sea crossings. Now, in their haste to contain the disease, they ended up creating even bigger problems. Rachel: That's... frustrating. I understand the urgency—you can't exactly schedule a two-week brainstorming session when something like that happens. So, what's the alternative? Inaction? Autumn: Not inaction, deliberation. Rosling argues that critical analysis can still happen swiftly if you're prepared. The key is to slow down just enough to gather reliable data and consult with experts. With better context and collaboration, responses become more effective. Rachel: Okay, so, it's the rational approach that prioritizes facts over fear. Not about dragging your heels, but cutting through the noise and basing decisions on solid information. Autumn: And that's where his advice overlaps beautifully with the next idea: cultivating a mindset of curiosity and learning. If you've done the homework and have some background knowledge, you're more likely to react with clarity rather than just confusion. Rachel: Alright, curiosity sounds great... in theory. But how do you turn curiosity from a "nice to have" into a genuine way of life? Autumn: Well, one thing Rosling emphasizes is questioning assumptions. He would frequently challenge audiences to re-evaluate their beliefs about global poverty or health, by using thought-provoking questions backed by data. Like when he asked audiences, "Are more people living in extreme poverty today compared to fifty years ago?" And most got it wrong. Rachel: Because the gut reaction is, “Of course poverty is worse now!” But the reality is...? Autumn: The reality is: Extreme poverty has plummeted. Went from roughly 85% of the population in 1800 to under 10% today. That's the type of curiosity we need – testing what we think we know. Rachel: And, if I had to guess, that’s where tools like Gapminder and Dollar Street come in? Autumn: Absolutely. Because those tools bring data to life. Rather than just reading that poverty is declining, you can use Dollar Street to ‘visit’ homes at different income levels. You see what life at Level 2 looks like. Families who now have bicycles, who've replaced open flames with gas burners. Progress that's tangible, even if it's not glamorous. Rachel: I get it. Curiosity and tools like that encourage understanding. But let's be honest: Can this curiosity mindset actually fix anything on a large scale? Autumn: Yes, especially when we combine it with systemic thinking. Rosling emphasizes looking for long-term solutions over a short-term, instant gratification fix. Just convincing individual parents to vaccinate is not enough. So, overcoming logistical hurdles, like ensuring vaccines reach remote areas and training healthcare workers plays a big role globally. Rachel: Scaling up from individual efforts to structural change. Got it. Autumn: Exactly. Understanding interconnected parts of a system, you'll see where action has the greatest impact. Rachel: Alright, I'll bite. This is starting to sound like a framework for not just ‘thinking factually,’ but actually living more wisely. Autumn: That's the point! Rosling's advice builds empathy too. Visualizing global progress helps us move beyond stereotypes because we see humans behind data. It's hard to paint someone as ‘just poor’ after you've seen a child on Level 2 improve their literacy because now they have access to electric light for studying. Rachel: So, full circle. We match data with humility, admit we don’t have all the answers, and use data to guide smarter decisions. Autumn: Bingo. By resisting blame, managing urgency, and fostering curiosity, we not only grow personally, but also contribute to collective progress. It's about aligning facts with humanity, and that's a pretty powerful way to navigate the world. Rachel: Alright, Autumn. Now, I'm genuinely reflecting on those times I jumped to conclusions or reacted too rashly, facts be damned! What would Rosling say to that? Autumn: He'd probably smile and tell you that wondering is half the battle won. Once you start asking questions, you've already taken that first step toward learning and growing.

Conclusion

Part 5

Autumn: Okay, so to recap, today we really dug into some of those, shall we say, “less helpful” instincts our brains throw at us, right? The Gap Instinct, Negativity Instinct, Fear Instinct – all those biases that can really skew how we see the world, making it seem way more bleak than it actually is. Rachel: And then we looked at Rosling's solutions, tools like Gapminder and Dollar Street. They're not just pretty charts; they actively challenge our preconceptions and make these huge global trends, like, “graspable”. Honestly, turns out the world is way more complex and ever-changing than we give it credit for. And progress? Apparently, that's a thing! Autumn: Precisely! And that adopting a fact-based perspective, you know, a truly informed worldview, isn't just about having access to the right data. It's really about cultivating curiosity, being humble enough to admit what you don't know, and focusing on the systems that create problems instead of just pointing fingers. It's a whole approach to life, really. Rachel: So here's the bottom line, everyone. The next time your newsfeed is flooded with the latest apocalypse-du-jour, just pump the brakes. Ask yourself, "Okay, but what do the actual “facts” say?" Push past those knee-jerk reactions and look at the data. Because seeing the world as it truly is, warts and all, is the first step to, you know, “actually” making things better. Autumn: And remember – and this is key – progress isn't about the absence of problems. It’s about having the ability to solve those problems, and doing so from a place of clarity and, dare I say, optimism. So, let's all try to replace fear with understanding, despair with curiosity, shall we? Rachel: Alright, Autumn, you've given me a lot to mull over. I think I might need to check out Gapminder myself. Autumn: Well, on that note, thanks everyone for tuning in! Until next time, stay curious, stay humble, and most importantly, stay factful!